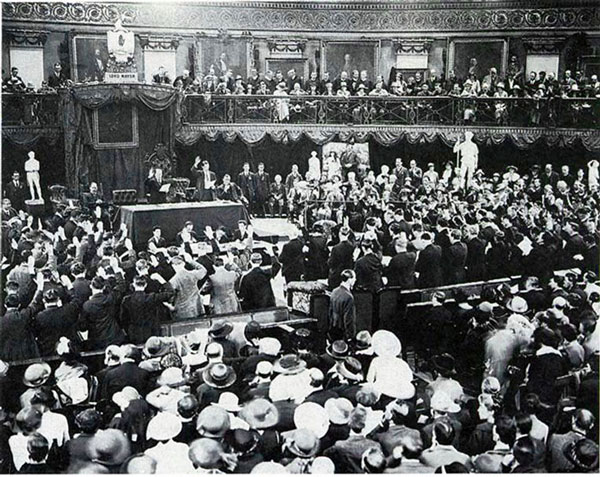

Kings Speech June 22nd 1921

THE KING’S SPEECH.

”The Northern Parliament on June 22, 1921′.

THE following is the text of the King’s Speech from the Throne in opening the Northern Parliament:-

Members of the Senate and of the House of Commons—For all who love Ireland, as I do with all my heart, this is a profoundly moving occasion in Irish history.

My memories of the Irish people date back to the time when I spent many happy days in Ireland as a midshipman. My affection for the Irish people has been deepened by successive visits since that time, and I have watched with constant sympathy the course of their affairs.

I could not have allowed myself to give Ireland, by deputy alone, my earnest prayers and good wishes.in the new era which opens with this ceremony, and I have, therefore, come in person, as Head of the Empire, to inaugurate this

Parliament on Irish soil. I inaugurate it with deep-felt hope, and I feel assured that you will do your utmost to make it an instrument of happiness and good government for all parts of the community which you represent.

This,is a great and critical occasion in the history of the six counties, but not for the six counties alone; for everything which interests them touches Ireland, and everything which touches Ireland finds an echo in the remotest parts of the Empire.

Few things are more earnestly desired throughout the English-speaking world than a satisfactory solution of the age-long Irish problems, which for generations embarrassed our forefathers, as they now weigh heavily upon us. Most certainly there is no wish nearer my own heart than that every man of Irish birth, whatever be his creeds and wherever be his home, should work in co-operation with the free communities on which the British Empire is based. I am confident that the important matters entrusted to the control and guidance of the Northern Parliament will be managed with wisdom and moderation; with fairness and due regard to every faith and interest, and with no abatement of that patriotic devotion to the Empire which you proved so gallantly in the Great War.

Full partnership in the United Kingdom and religious freedom Ireland has long enjoyed. She now has conferred upon her the duty of dealing with all the essential tasks of domestic legislation and government, and I feel no misgiving as to the spirit in which you who stand here to-day will carry out the all-important functions entrusted to your care. My hope is broader still. The eyes of the whole Empire are on Ireland to-day—that Empire in which so many nations and races have come together in spite of the ancient feuds, and in which new nations have come to birth within the life-time of the youngest in this hall. I am emboldened by that thought to look beyond the sorrow and anxiety which have clouded of late my vision of Irish affairs. I speak from a full heart when I pray that my coming to Ireland to-day may prove to be the first step towards the end of strife amongst her people, whatever their race or creed. In that hope I appeal to all Irishmen to pause, to stretch out the hand offorbearance and conciliation, to forgive and forget, and to join in making for the land they love a new era of peace, contentment and goodwill. It is my earnest desire that in Southern Ireland, too, there may, ere long, take place a parallel to what is now passing in this hall; that there a similar occasion may present itself, and a similar ceremony be performed.

For this the Parliament of the United Kingdom has in the fullest measure provided the powers. For this the Parliament of Ulster is pointing the way. The future lies in the hands of my Irish people themselves. May this historic gathering be the prelude of the day in which the Irish people, north and south, under one Parliament or two, as those Parliaments may themselves decide, shall work together in common love for Ireland upon the sure foundation of mutual justice and respect.

II.

The Prime Ministers Message to the King.

I am confident that I can speak not only for the Government of the United Kingdom, but for the whole Empire, in offering Your Majesty and the Queen thehearty congratulations of all your loyal subjects on the success of your visit to Belfast. We have been deeply moved by the devotion and enthusiasm with which you were greeted, and our faith in the future is strengthened by the reception given to Your Majesty’s words in inaugurating the Parliament of Northern Ireland. None but the King could have made that personal appeal; none but the King could have evoked so instantaneous a response. No effort shall be lacking on the part of your Ministers to bring Northern and Southern Ireland together in recognition of a common Irish responsibility, and I trust that from now onwards a new spirit of forbearance and accommodation may breathe upon the troubled waters of the Irish question. Your Majesty may rest assured of the deep gratitude of your peoples for this new act of Royal service to their ideals and interests.

III.

The King’s Reply to the. Prime Minister.

His Majesty sent the following reply :— The Queen and I have received with warm gratitude your message of congratulations upon the happy conclusions of our visit to Belfast. W e are moved beyond expression, not only by the enthusiastic greeting given to us in Northern Ireland, but also by the general reception in all quarters of the words which I spoke, and spoke with all my heart. Those services to my people, to which you so generously refer in your message, will be more than amply rewarded if they assist in any way the efforts of my Government to bridge over the unhappy differences standing between the Irish people, and that peaceful settlement for which the whole English-speaking world so earnestly looks.

II.

The Prime Ministers Message to the King.

I am confident that I can speak not only for the Government of the United Kingdom, but for the whole Empire, in offering Your Majesty and the Queen thehearty congratulations of all your loyal subjects on the success of your visit to Belfast. We have been deeply moved by the devotion and enthusiasm with which you were greeted, and our faith in the future is strengthened by the reception given to Your Majesty’s words in inaugurating the Parliament of Northern Ireland. None but the King could have made that personal appeal; none but the King could have evoked so instantaneous a response. No effort shall be lacking on the part of your Ministers to bring Northern and Southern Ireland together in recognition of a common Irish responsibility, and I trust that from now onwards a new spirit of forbearance and accommodation may breathe upon the troubled waters of the Irish question. Your Majesty may rest assured of the deep gratitude of your peoples for this new act of Royal service to their ideals and interests.

III.

The King’s Reply to the. Prime Minister.

His Majesty sent the following reply :— The Queen and I have received with warm gratitude your message of congratulations upon the happy conclusions of our visit to Belfast. W e are moved beyond expression, not only by the enthusiastic greeting given to us in Northern Ireland, but also by the general reception in all quarters of the words which I spoke, and spoke with all my heart. Those services to my people, to which you so generously refer in your message, will be more than amply rewarded if they assist in any way the efforts of my Government to bridge over the unhappy differences standing between the Irish people, and that peaceful settlement for which the whole English-speaking world so earnestly looks.

IV.

The Terms of the Armistice.

The following conditions were agreed to on Saturday, the 9th July, 1921 :—On behalf of the British Army it was agreed as follows :—

1. No incoming troops, R.I.C., and Auxiliary Police and munitions except maintenance drafts.

2. No provocative display of troops, armed or unarmed..

3. It is understood that all provisions of this truce apply to the martial law area equally with the rest of Ireland.

4. No pursuit of Irish officers or men, or war material or military stores.

5. No secret agents noting descriptions or movements, and no interference with the movements of Irish persons, military or civil, and no attempts to discover the haunts or habits of Irish officers and men. Note: This supposes the abandonment of curfew restrictions. No pursuit or observance of lines of communication or connection.

On behalf of the Irish Army it is agreed :—

(a.) Attacks on Crown Forces and civilians to cease.

(6.) No provocative displays of forces, armed or unarmed.

(c.) No interference with Government or private property.

id.) To discountenance and prevent any action likely to cause disturbance of the peace which might necessitate military interference.

V.

Letter from the Prime Minister to Sir James Craig and Mr. de Valera.

Sir, 10, Downing Street, S.W., June 24, 1921.

The British Government are deeply anxious that, so far as they can assure it, the King’s appeal for reconciliation in Ireland shall not have been made in vain.

Rather than allow yet another opportunity of settlement in Ireland to be cast aside, they feel it incumbent upon them to make a final appeal in the spirit of the King’s words for a conference between themselves and the representatives of Southern and Northern Ireland.

I write, therefore, to convey the following invitation to you as the chosen leader of the great majority in Southern Ireland, and to Sir James Craig, the Premier of Northern Ireland :—

1. That you attend a conference here in London, in company with Sir James Craig, to explore to the utmost the possibility of a settlement.

2. That you should bring with you for the purpose any colleagues whom you may select. The Government will, of course, give a safe conduct to all who may be chosen to participate in the conference.

* *

We make this invitation with a fervent desire to end the ruinous conflict which has for centuries divided Ireland and embittered the relations of the peoples of these two islands, who ought to live in neighbourly harmony with each other, and whose co-operation would mean so much, not only to the Empire, but to humanity.

We wish that no endeavour should be lacking on our part to realise the King’s prayer, and we ask you to meet us, as we will meet you, in the spirit of conciliation for which His Majesty appealed.

I am, Sir,

Your obedient servant,

(Signed) D. LLOYD GEORGE.

The Prime Minister sent simultaneously an invitation in like terms to Sir James Craig, Premier of Northern Ireland.

VI.

Sir James Craig’s Reply to the Prime Minister.

My Dear Prime Minister, Belfast, June 26, 1921.

I am in receipt of your letter of the 24th inst., conveying an invitation to a conference in London at an early date; I avail myself of your courier to intimate that I am summoning a meeting of my Cabinet for Tuesday, when I hope to be able to obtain the presence of all the members, and you may rest assured that no time will be lost in intimating the result of our deliberations.

JAMES CRAIG.

VIl.

Mr. de Valera’s Reply to the Prime Minister.

The Right Hon. David Lloyd George,

10, Downing Street, London.

Sir, ” Dublin, June 28, 1921.

I have received your letter. I am in consultation with such of the principal representatives of our nation as are available. We most earnestly desire to help in bringing about a lasting peace between the peoples of these two islands, but see no avenue by which it can be reached if you deny Ireland’s essential unity and set aside the principle of national self-determination.

Before replying more fully to your letter, I am seeking a conference with certain representatives of the political minority in this country.

(Signed) EAMON D E VALERA,

Mansion House, Dublin.

VIII.

Letter from Mr. de Valera to:—

Sir James Craig.

The Earl of Midleton.

Sir Maurice E. Dockrell.

Sir Robert H. Woods.

Mr. Andrew Jameson.

A Chara, Dublin, June 28, 1921.

The reply which I, as spokesman for the Irish nation, shall make to Mr. Lloyd George will affect the lives and fortunes of the political minority in this island, no less than those of the majority.

Before sending that reply, therefore, I would like to ,confer with you and to learn from you -at first hand the views of a certain section of our people, of whom you are representative.

I am confident that you will not refuse this, service to Ireland, and I shall await you at the Mansion House, Dublin, at 11 A . M . on Monday next, in the hope that you will find it possible to attend.

Mise

(Signed) ‘ EAMON D E VALERA.

IX.

Sir James Craig’s further Reply to the Prime Minister.

(Telegram,.)

Prime Minister, 10, Downing Street, S.W.

Dear Prime Minister, Belfast, June 28, 1921.

With further reference to your communication of the 24th instant, as a result of the decision of my Cabinet this morning, I am now in a position to reply. In view of the appeal conveyed to us by His Majesty in His gracious message on the opening of the Northern Parliament for peace throughout Ireland, we cannot refuse to accept your invitation to a conference to discuss how best this can be accomplished. I propose to bring with me :—

Right Hon. H. M. Pollock, Minister of Finance.

Right Hon. J. M. Andrews, Minister of Labour

Right Hon. the Marquis of Londonderry, K.G., Minister of Education.

Right Hon. E. M. Archdale, Minister of Agriculture-.

Will you kindly inform me of the place and hour of meeting,

Yours sincerely,

(Signed) JAMES CRAIG.

Right Hon. D. Lloyd George, M.P.

X.

To Sir James Craig, Craigavon, co. Down.

Can you come Dublin Monday next, 11 a.m.’? On receipt of your reply will write you.

Eamon de Valera, Mansion House, Dublin.

XI.

Telegram from Sir James Craig to Mr. de Valera.

In reply to this Sir James Craig immediately telegraphed:—

Impossible for me to arrange any meeting. I haye already accepted the Prime Ministers invitation to London Conference, and, in order to obviate misunderstanding in press between my namesake in the Southern Parliament and myself I am publishing these telegrams.

(Signed) JAMES CRAIG.

Prime Minister of Northern Ireland.

Note.—Mr. de Valera’s telegram was wrongly addressed, Sir James Craig being resident at Cabin Hill and not at Craigavon.

XII.

Mr. de Valera’s Reply to Sir James Craig.

Sir James Craig, City Hall, Belfast.

Sir, ‘ Dublin, June 29, 1921.

I greatly regret you cannot come to conference here on Monday. Mr. Lloyd George’s-proposal, because of its implications, impossible of acceptance in its present form. Irish political differences ought to be adjusted, and can, I believe, be adjusted, on Irish soil. But it is obvious that in negotiating peace with Great Britain the Irish delegation ought not to be divided, but should act as a unit on some common principle.

(Signed) E. DE VALERA:

XIII.

The Prime Minister Letter to Lord Midleton.

Dear Lord Midleton, 10, Downing Street, S.W., July 7, 1921.

In reference to the conversation I had with you this morning, the Government fully realise that it would be impossible to conduct negotiations, with any hope of achieving satisfactory results, if there is bloodshed and violence in Ireland. It would disturb the atmosphere, and make the attainment of peace diflicult. As soon as we hear that Mr. de Valera is prepared to enter into conference with the British Government, and to give instructions to those under his control to cease from all acts of violence, we should give instructions to the troops and to the police to suspend active operations against those who are engaged in this unfortunate conflict.

Yours sincerely,

(Signed) D. LLOYD GEORGE.

Xllll

The Right Honourable David Lloyd George,

10, Downing Street, London.

Sir, Mansion House, -Dublin, July 8, 1921.

The desire you’ express on the part of the British’ Government to end the centuries of conflict between the peoples of these two islands, and to establish relations of neighbourly harmony, is the genuine desire of the people of Ireland. I have consulted with my colleagues, and secured the views of representatives of the minority of our nation in regard to the invitation you have sent me. In reply, I desire to say that I am ready to meet and discuss with you on what bases such a conference as that proposed can reasonably hope to achieve the object desired.

I am, Sir, faithfully yours,

(Signed) EAMON D E VALERA.

XV.

The Prime Ministers Reply to Mr. de Valera.

E. de Valera, Mansion House, Dublin. London, July 10 1921

I have received your letter of acceptance, and shall be happy to see you and any colleagues whom you wish to bring with you at Downing Street any day this week -Please wire the date of your arrival in London.

XVI.

Telegram from Mr. de Valera to the Prime Minister.

Right Honourable David Lloyd George, Dublin, July 10, 1921.

Telegram received. I will be in London for conference on Thursday next.

(Signed) E..D E VALERA.

XVII.

Proposals of the British Government for an Irish Settlement,

July 20, 1921.

(Handed by the Prime Minister to Mr. de Valera on July 20, 1921.)

The British Government are actuated by an earnest desire to end the unhappy divisions between Great Britain and Ireland which have produced so many conflicts in the past and which have – once more shattered the peace and well-being of Ireland at the present time. They long with His Majesty the King, in the words of His Gracious Speech in Ireland last month, for a satisfactory solution of “those age-long Irish problems which for generations embarrassed our forefathers; as they now weigh heavily upon us”; and they wish to do their utmost to secure that ” every man of Irish birth, whatever be his creed and wherever be his home, should work in loyal co-opera/tion with the free communities on which the British Empire is based.” They are convinced that the Irish people may find as worthy and as complete an expression of their political and spiritual ideals within the Empire as any of the numerous and varied nations united in allegiance to His Majesty’s Throne ; and they desire such a consummation, not only for the welfare of Great Britain, Ireland and the Empire as a whole, but also for the cause of peace and harmony throughout the world. There is no part of the world where Irishmen have made their home but suffers from our ancient feuds; no part of it but looks to this meeting between the British Government and the Irish leaders to resolve these feuds in a new understanding, honourable and satisfactory to all the peoples involved.

The free nations which compose the British Empire are drawn from many races, with different histories, traditions and ideals. In the Dominion of Canada, British and French have long forgotten the bitter conflicts which divided their ancestors. In South Africa the Transvaal Republic and the Orange Free State have joined with two British colonies to make a great self-governing union under His Majesty’s sway. The British people cannot believe that where Canada and- South Africa, with equal or even greater difficulties, have so signally succeeded, Ireland will fail; and they are determined that, so far as they themselves can assure it, nothing shall hinder Irish statesmen from joining together to build up an Irish State in free and willing co-operation with the other peoples of the Empire.

Moved by.these considerations, the British Government invite Ireland to take her place in the great association of free nations over which His Majesty reigns. As earnest of their desire to obliterate old quarrels and to enable Ireland to face the future with her own strength and hope, they propose that Ireland shall assume forthwith the status of a Dominion, with all the powers and privileges set forth in this document. By the adoption of Dominion status it is understood that Ireland shall enjoy complete autonomy in taxation and finance ; that she shall maintain her own courts of law and judges ; that she shall maintain her own military forces for home defence, her own constabulary and her own police ; that she shall take over the Irish postal services and all matters relating thereto, education, land, agriculture, mines and minerals, forestry, housing, labour, unemployment, transport, trade, public health, health insurance and the liquor traffic ; and, in sum, that the shall exercise all those powers and privileges upon which the autonomy of the self-governing Dominions is based, subject only to the considerations set out in the ensuing paragraphs. Guaranteed in these liberties, which no foreign people can challenge without challenging the Empire as a whole, the Dominions hold each and severally by virtue of their British fellowship a standing amongst the nations equivalent, not merely to their individual strength, but to the combined power and influence of all the nations of the Commonwealth. That guarantee, that fellowship, that freedom the whole Empire looks to Ireland to accept.

To this settlement the British Government are prepared to give immediate effect upon the following conditions, which are, in their opinion, vital to the welfare and safety of both Great Britain and Ireland, forming as they do the heart of the Commonwealth:—

I. The common concern of Great Britain and Ireland in the defence of their interests by land and sea shall be mutually recognised. Great Britain lives by sea-borne food ; her communications depend upon the freedom of the great sea routes. Ireland lies at Britain’s side across the sea-ways north and south that link her with the sister nations of the Empire, the markets of the world and the vital sources of her food supply. In recognition of this fact, which nature has imposed and no statesmanship can change, it is essential that the Royal Navy alone should control the seas around Ireland and Great Britain, and that such rights and liberties should be accorded to it by the Irish State as are essential for naval purposes in the Irish harbours and on the Irish coasts.

II . In order that the movement towards the limitation of armaments which is now making progress in the world should in no way be hampered, it is stipulated that the Irish Territorial Force shall, within reasonable limits, conform in respect of numbers to the military establishments of the other parts of these islands.

III . The position of Ireland is also of great importance for the air services, both military and civil. The Royal Air Force will need facilities for all purposes that it serves, and Ireland will.form an essential link in the development of air routes between the British Isles and the North American continent. It is therefore stipulated that Great Britain shall have all necessary facilities for the development of-defence and of communications by air.

IV. Great Britain hopes that Ireland will, in due course and of her own free will, contribute in proportion-to her wealth to the Regular Naval, Military and Air Forces of the Empire. It is further assumed that voluntary recruitment for these forces will be permitted throughout Ireland, particularly for those famous Irish regiments which have so long and so gallantly served His Majesty in all parts of the, world.

Letter from Sir James Craig to the Prime Minister.

My Dear Prime Minister, . Belfast, July 29, 1921.

Your proposals for an Irish settlement have now been exhaustively examined by my Cabinet and myself. We realise that the preamble is specially addressed to Mr. de Valera and his followers, and observe that it implies that difficulties have long existed throughout the Empire and America attributable to persons of Irish extraction. In fairness to the Ulster people, I must point out that they have always aimed at the retention of their citizenship in the United Kingdom and Empire of which they are proud to form part, and that there are not to be found in any quarter of the world more loyal citizens than those of Ulster descent. They hold fast to cherished traditions, and deeply resent any infringement of their rights and privileges, which belong equally to them and to the other citizens within the Empire.

In order that you may correctly understand the attitude we propose to adoptit is necessary that I should call to your mind the sacrifices we have so recently made in agreeing to self-government and consenting to the establishment of a Parliament for Northern Ireland. Much against our wish, but in the interests of peace, we accepted this as a final settlement of the long-outstanding difficulty with which Great Britain has been confronted. We are now busily engaged in ratifying our part of this solemn bargain, while Irishmen outside the Northern area, who in the past struggled for Home Rule, have chosen to repudiate the Government of Ireland Act and to press Great Britain for wider power. To join in such pressure is repugnant to the people of Northern Ireland.

In the further interest of peace we therefore respectfully decline to determine or interfere with the terms of settlement between Great Britain and Southern Ireland. It cannot then be said that ” Ulster blocks the way.” Similarly, if there exists an equal desire for peace on the part of Sinn Eein, they will respect the status quo in Ulster and will refrain from any interference with our Parliament and rights, which under no circumstances can we permit. In adopting this course we rely on the British people, who charged us with the responsibility of undertaking our parliamentary institutions, to safeguard the ties that bind us to Great Britain and the Empire, to ensure that we are not prejudiced by any terms entered into between them and Mr. de Valera, and to maintain the just equality exhibited throughout the Government of Ireland Act.

Our acceptance of your original invitation to meet in conference still holds good, and if at any time our assistance is again desired we are available, but I feel bound to acquaint you that no meeting is possible between Mr. de Valera and myself until he recognises that Northern Ireland will not submit to any authority other than His Majesty the King and the Parliament of the United Kingdom, and admits the sanctity of the existing powers and privileges of the Parliament and Government of Northern Ireland. In conclusion, let me assure you that peace is as earnestly desired by my Government and myself as by you and yours, and that, although we have nothing left to us to give away, we are prepared, when you and Mr. de Valera arrive at a satisfactory settlement, to co-operate with Southern Ireland on equal terms for the future welfare of our common country. In order to avoid any misunderstanding or misrepresentation of our views I intend to publish this letter when your proposals are made public.

Yours sincerely,

(Signed) JAMES CRAIG.

V. While the Irish people shall enjoy complete autonomy in taxation and finance, it is essential to prevent a recurrence of ancient differences between the two Islands, and in particular to avert the possibility of ruinous trade wars.

With this object in view, the British and Irish Governments shall agree to impose no protective duties or other restrictions upon the flow of transport, trade and commerce between all parts of these islands.

VI. The Irish people shall agree to assume responsibility for a share of the present debt of the United Kingdom and of the liability for pensions arising out of the great war, the share, in default of agreement between the Governments concerned, to be determined by an independent arbitrator appointed from within His Majesty’s dominions. In accordance with these principles, the British Government propose that the conditions of settlement between Great Britain and Ireland shall be embodied in the form, of a treaty, to which effect shall in due course be given by the British and Irish Parliaments. They look to such an instrument to obliterate old conflicts forthwith, to clear the way for a detailed settlement in full accordance with Irish conditions and needs, and thus to establish.a new and happier relation between Irish patriotism and that wider community of aims ‘and interests by which the unity of the whole Empire is freely sustained. The form in which the settlement is to take effect will depend upon Ireland herself. It must allow for full recognition of the existing powers and privileges of the Parliament and Government of Northern Ireland, which cannot be abrogated except by their own consent. For their part, the British Government entertain an earnest hope that the necessity of harmonious co-operation amongst Irishmen of all classes and creeds will be recognised throughout Ireland, and they will welcome the day when by these means unity is achieved, but no such common action can be secured by force.

Union came in Canada by the free consent of the provinces. So in Australia; so in South Africa. It will come in Ireland by no other way than consent. There can, in fact, be no settlementon terms involving, on the one side – or the other, that bitter appeal to bloodshed and violence which all men of goodwill are longing to terminate. The British Government will undertake to give effect, so far as that depends on them, to any terms in this respect on which all Ireland unites. But in no conditions can they consent to any proposals which would kindle civil war in Ireland. Such a war would not touch Ireland alone, for partisans would flock to either side from Great Britain, the Empire and elsewhere with consequences more devastating to the welfare both of Ireland and the Empire than the conflict to which a truce has been called this month. Throughout the Empire there is a deep desire that the day of violence should pass and that a solution should be found, consonant with the highest ideals and interests of all parts of Ireland, which will enable her to co-operate as a willing partner in the British Commonwealth.

The British Government will therefore leave Irishmen themselves to determine by negotiations between them whether the new powers which the pact defines shall be taken over by Ireland as a whole and administered by a single Irish body, or taken over separately by Southern and Northern Ireland, with or without a joint authority to harmonise their common interests. They will willingly assist in the negotiation of such a settlement, if Irishmen should so desire. By these proposals the British Government sincerely believe that they will have shattered the foundations of that ancient hatred and distrust which have disfigured our common history for centuries past. The future of Ireland within the Commonwealth is for the Irish people to shape. In the foregoing proposals the British Government have attempted no more than the broad outline of a settlement. The details they leave for discussion when the Irish people have signified their acceptance of the principle of this pact..

(Signed) ‘ D. LLOYD GEORGE.

10, Downing Street, S.W. 1,

July 20, 1921.

Eamon de Valera, Esq.,

Mansion House, Dublin. Savoy Hotel, London,

My dear de Valera, August 4, 1921.

Lane duly reported to me the substance of his conversations with you, and handed me your letter of the 31st July. He told me of your anxiety to meet and discuss the situation with Ulster representatives. Since,then I have, as I wired you yesterday, done my best to bring about such a meeting, but Sir James Craig, while willing to meet you in a conference with Mr. Lloyd George, still remains unwilling to meet you in his absence, and nothing that I have been able to do or say has moved him from that attitude. If you were to request a meeting with him, he will reply setting forth his position and saying that Ulster will not be moved from the constitutional position which she occupies under the existing legislation; she is satisfied with her present status, and will on no account agree to any change.

On the other hand, both in your conversation with Lane and in your letter you insist on Ulster coming into a United Ireland constitution, and unless that is done you say that no further progress can be made. There is therefore an impasse which I do not at present know how to get over. Both you and Craig are equally immovable. Force as a solution of the problem is out of the question both on your and his premises. The process of arriving at an agreement will therefore take time. The result is that at this stage I can be of no further use in this matter, and I have therefore decided to adhere to my plan of sailing for South Africa to-morrow.

This I regret most deeply, as my desire to help in pushing the Irish settlement one stage further has been very great. But I must bow to the inevitable. I should like to add a word in reference to the situation as I have come to view it. I have discussed it very fully with you and your colleagues. I have also probed as deeply as I could into the Ulster position. My conviction is that for the present no solution based on Ulster coining into the Irish State will succeed. Ulster will not agree, she cannot be forced, and any solution on those lines is at present foredoomed to failure. I believe that it is in the interest of Ulster to come in, and that the force of Community of interests will, over a period of years, prove so great and compelling that Ulster will herself decide to join the Irish State. But at present an Irish Settlement is only possible if the hard facts are calmly faced and Ulster is left alone. Not only will she not consent to come in, but even if she does, the Irish State will, I fear, start under such a handicap of internal friction and discordance that the result may well be failure once more.

My strong advice to you is to leave Ulster alone for the present, as the only line along which a solution is practicable ; to concentrate on a free constitution for the remaining twenty-six counties, and, through a successful running of the Irish State and the pull of economic and other peaceful forces, eventually to bring Ulster into that State. I know how repugnant such a solution must be to -all Irish patriots, who look upon Irish unity as a sine qua non of any Irish settlement. But the wise man, while fighting for his ideal to the uttermost, learns also to bow to the inevitable. And a humble acceptance of the facts is often the only way of finally overcoming them. It proved so in South Africa, where ultimate unity was only realised through several stages and a process of years, and where the republican ideal for which we had made unheard-of sacrifices had ultimately to give way to another form of Freedom.

My belief is that Ireland is travelling the same painful road as South Africa, and that with wisdom and moderation in her leadership she is destined to achieve no less success. As I said to you before, I do not consider one single clean-cut solution of the Irish question possible at present. You will have to pass through several stages, of which a free constitution for Southern Ireland is the first, and the inclusion of Ulster and the full recognition of Irish unity will be the last. Only the first stage will render the last possible, as cause generates effect. To reverse the process and to begin with Irish unity as the first step is to imperil the whole settlement. Irish unity should be the ideal to which the whole process should be directed.

I do not ask you to give up your ideal, but only to realise it in the only way which seems to me at present practicable. Freedom will lead inevitably to unity; therefore begin with Freedom—with a free constitution for the twenty-six counties—as the first and most important step in the whole settlement.

As to the form of that Freedom, here, too, you are called upon to choose between two “alternatives. To you, as you say, the republic is the true expression of national self-determination. But it is not the only expression, and it is an expression which means your final and irrevocable severance from the British League. And to this, as you know, the Parliament and people of this country will not agree.

The British Prime Minister has made you an offer of the other form of Freedom—of Dominion status—which is working with complete success in all parts of the British League. Important British Ministers have described Dominion status in terms which must satisfy all you could legitimately wish for. Mr. Lloyd George, in his historic reply to General Hertzog at Paris, Mr. Bonar Law, in a celebrated declaration in the House of Commons, Lord Milner, as Secretary of State for the Colonies, have stated their views, and they coincide with the highest claims which Dominion statesmen have ever put forward on behalf of their free nations. What is good enough for these nations ought surely to be good enough for Ireland, too. For Irishmen to say to the world that they will not be satisfied with the status of the great British Dominions would be to alienate all that sympathy which has so far. been the main support of the Irish cause

The British Prime Minister offers complete Dominion status to the twenty-six counties, subject to certain strategic safeguards which you are asked to agree to voluntarily as a free Dominion, and which we South Africans agreed to as a free nation in the Union of South Africa. To my mind, such an offer by a British Prime Minister, who-unlike his predecessors—is in a position to deliver the goods, is an event of unique importance. You are no longer offered a Home Rule scheme of the Gladstone or Asquith type, with its limited powers and reservations of a fundamental character. Full Dominion status, with all it is and implies, is yours-if you will but take it. It is far more than was offered the Transvaal and Free State, who fought for Freedom one of the greatest wars in the history of Great Britain, and one which reduced their own countries to ashes and their little people to ruins.

They accepted the far less generous offer that was made to them; from that foothold they then proceeded to improve their position, until to-day South Africa is a happy, contented, united and completely free country. What they have finally achieved after years of warfare and political evolution is now offered you-not in doles or instalments, but at once and completely. If, as I hope, you accept, you will become a sister Dominion in a great circle of equal States, who will stand beside you and shield you and protect your new rights as if these were their own rights; who will view an invasion of your rights or a violation of your status as if it was an invasion and a violation of their own, and who will thus give you the most effective guarantee possible against any possible arbitrary interference by the British Government with your rights and position.

In fact, the British Government will have no further basis of interference with your affairs, as your relations with Great Britain will be a concern not of the British Government but of the Imperial Conference, of which Great Britain will be only one of seven members. Any questions in issue between you and the British Government will be for the Imperial Conference to decide. You will be a free member of a great League, of which most of the other members will be in the same position as yourself; and the Conference will be the forum for thrashing out any questions which may arise between members. This is the nature and the constitutional practice of Dominion Freedom.

The difficulty in Ireland is no longer a constitutional difficulty. I am satisfied that from the constitutional point of view a fair settlement of the Irish question is now possible and practicable. It is the human difficulty which remains. The Irish question is no longer a constitutional but mostly a human problem. A history such as yours must breed a temper, an outlook, passions, suspicions, which it is most difficult to deal with. On both sides sympathy is called for, generosity and a real largeness of soul. I am sure that both the English and Irish peoples are ripe for a fresh start. The tragic horror of recent events, followed so suddenly by a truce and fraternising all along the line, has set flowing deep fountains of emotion in both peoples and created a new political situation. It would be the gravest reflection on our statesmanship if this auspicious moment is allowed to pass. You and your friends have now a unique opportunity— such as Parnell and his predecessors and successors never had—to secure an honourable and lasting peace for your people.

I pray to God that \ou may be wisely guided, and that peace may now be concluded, before tempers again change and perhaps another generation of strife ensues.

Ever yours sincerely,

(Signed) J. C. SMUTS.

XIX.

Reply from Mr. de Valera.

The Right Hon. David Lloyd George,

10, Downing Street,

Whitehall, London. Office of the President, Dublin,

Sir, Mansion House, August 10, 1921.

On the occasion of our last interview I gave it as my judgment that Dail Eireann could not, and that the Irish people would not, accept the proposals of your Government as set forth in the draft of the 20th July, which you had presented to me. Having consulted my colleagues, and with them given these proposals the’ most earnest consideration, I now confirm that judgment.

The outline given in the draft is self-contradictory, and ” the principle of the pact” not easy to determine. To the extent that it implies a recognition of Ireland’s separate nationhood and her right to self-determination we appreciate and accept it. But in the stipulations and express conditions concerning the matters that are vital the principle is strangely set aside and a claim advanced by your Government to an interference in our affairs and to a control which we cannot admit.

Ireland’s right to choose for herself the path she shall take to realise her own destiny must be accepted as indefeasible, it is a right that has been maintained through centuries of oppression and at the cost of unparalleled sacrifice and untold suffering, and it will not be surrendered. We cannot propose to abrogate or impair it, nor can Britain or any other foreign State or.group of States legitimately claim to interfere with its exercise in order to serve their own special interests. The Irish people’s belief is that the national destiny can best be-realised in political detachment, free from imperialistic entanglements which they feel will involve enterprises out of harmony with the national character, prove destructive of their ideals, and be fruitful only of ruinous wars, crushing burdens, social discontent, and general unrest and unhappiness. Like “the small States of Europe, they are prepared to hazard their independence on the basis of moral right, confident that as they “would threaten.no nation or people, they would in turn be free from aggression themselves. This is the policy they have declared for in plebiscite after plebiscite, and the degree to which any other line of policy deviates from it must be taken as a measure of the extent to which external pressure is operative and violence is being done to the wishes of the majority.

As for myself and my colleagues, it is our deep conviction that true friendship with England, which military coercion has frustrated for centuries, can be obtained most readily now through amicable but absolute separation. The fear, groundless though we believe it to be, that Irish territory may be used as the basis for an attack upon England’s liberties can be met by reasonable guarantees not inconsistent with Irish sovereignty. “Dominion status” for Ireland everyone who understands the conditions knows to be illusory. The freedom which the British Dominions enjoy is not so much the result of legal enactments or of treaties as of the immense distances which separate them from Britain, and have made interference by her impracticable. The most explicit guarantees, including the Dominions’ acknowledged right to secede, would be necessary to secure for Ireland an equal degree of freedom. There is no suggestion, however, in the proposals made of any such guarantees. Instead, the natural position is reversed; our geographical situation with respect to Britain is made the basis of denials and restrictions unheard of in the case of the Dominions; the smaller island must give military safeguards and guarantees to the larger and suffer itself to be reduced to the position of a helpless dependency.

It should be obvious that we could not urge the acceptance of such proposals upon our people. A certain treaty of free association with the British Commonwealth group, as with a partial League of Nations, we would have been ready to recommend, and as a Government to negotiate and take responsibility for, had we an assurance that the entry of the nation as a whole into such association would secure for it the allegiance of the present dissenting minority, to meet whose sentiment alone this step could be contemplated. Treaties dealing with the proposals for free intertrade and mutual limitation of armaments we are ready at any time to negotiate. Mutual agreement for facilitating air communications, as well as railway and other communications, can, we feel certain, also be effected. No obstacle of any kind will be placed by us in the way of that smooth commercial intercourse which is essential in the life of both islands, each the best customer and the best market of the other. It must of course be understood that all treaties and agreements would have to be submitted for ratification to the National Legislature in the first instance, and subsequently to the Irish people as a whole, under circumstances which would make it evident that their decision would be a free decision, and that every element of military compulsion was absent. The question of Ireland’s liability ” for a share of the present debt of the United Kingdom” we are prepared to leave to be determined by a board of arbitrators, one appointed by Ireland, one by Great Britain, and a third to be chosen by agreement, or in default, to be nominated, say, by the President of the United States of America, if the President would consent.

As regards the question at issue between the political minority and the great majority of the Irish people, that must remain a question for the Irish people themselves to settle. We cannot admit the right of the British Government to mutilate our country, either in its own interest or at the call of any section of our population. We do not contemplate the use of force. If your Government stands aside, we can effect a complete reconciliation. We agree with you ” that no common action can be secured by force.” Our regret is that this wise and-true principle which your Government prescribes to us for the settlement of our local problem it seems unwilling to apply consistently to the fundamental problem of the relations between our island and yours The principle we rely on in the one case we are ready to apply in the other, but should this principle not yield an immediate settlement we are willing that this question too be submitted to.external arbitration.

Thus we are ready to meet you in all that is reasonable and just. The responsibility for initiating and effecting an honourable peace rests primarily not with our Government but with yours. We have no conditions to impose, no claims to advance but the one, that we be. freed from aggression. We reciprocate with a sincerity to be measured only by the terrible sufferings our people have undergone the desire you express for mutual and lasting friendship. The sole cause of the “ancient feuds” which you deplore has been, as we know, and as history proves, the attacks of English rulers upon Irish liberties. These attacks can cease forthwith, if your Government has the will.

The road to peace and understanding lies open.

I am, Sir,

Faithfully yours,

(Signed) EAMON DE VALERA.

August 10,1921.

Sir, , – 10, Downing Street, August 13, 1921.

The earlier part of your letter is so much opposed to our fundamental position that we feel bound to leave you in no doubt of our meaning. You state that after consulting your colleagues you confirm your declaration that our proposals are such as Dail Eireann could not, and the Irish people would not, accept. You add that the outline given in our draft is self-contradictory, and the principle of the pact offered to you not easy to determine. We desire, therefore, to make our position absolutely clear. In our opinion, nothing is to be gained by prolonging a theoretical discussion of the national status which you may be willing to accept as compared with that of the great self-governing Dominions of the British Commonwealth, but we must direct your attention to one point upon which you lay some emphasis, and upon which no British Government can compromise, namely, the claim that we should acknowledge the right of Ireland to secede from her allegiance to the King. No such right can ever be acknowledged by us. The geographical propinquity of Ireland to the British Isles is a fundamental fact. The history of the two islands for many centuries, however it is read, is sufficient proof that their destinies are indissolubly linked. Ireland has sent members to the British Parliament for more than a hundred years. Many thousands of her people during: all that time have enlisted freely and served gallantly in the forces of the Crown. Great numbers in all the Irish provinces are profoundly attached to the Throne. These facts permit of one answer, and one only, to the claim that Britain should negotiate with Ireland as a separate and foreign Power. When you, as the chosen representative of Irish national ideals, came to speak with me, I made one condition only, of which our proposals plainly stated the effect—that Ireland should recognise the force of geographical and historical facts. It is those facts which govern the problem of British and Irish relations. If they did not exist, there would be no problem to discuss. I pass therefore to the conditions which are imposed by these facts. W e set them out clearly in six clauses in our former proposals, and need not restate them here, except to say that the British Government cannot consent to the reference of any such questions, which concern Great Britain and Ireland alone, to the arbitration of a foreign Power.

We are profoundly glad to have your agreement that Northern Ireland cannot be coerced. This point is of great importance, because the resolve of our people to resist with their full power any attempt at secession by one part of Ireland carries with it of necessity an equal resolve to resist any effort to coerce another part of Ireland to abandon its allegiance to the Crown. We gladly give you the assurance that we will concur in any settlement which Southern and Northern Ireland may make for Irish unity within the six conditions already laid- down, which apply to Southern and Northern Ireland alike, but we cannot agree to refer the question of your relations with Northern Ireland to foreign arbitration.

The conditions of the proposed settlement do not arise from any desire to force our will upon people of another race, but from facts which are as vital to Ireland’s welfare as to our own. They contain no derogation from Ireland’s status as a Dominion, no desire for British ascendancy over Ireland, and no impairment of Ireland’s national ideals. Our proposals present to the Irish people an opportunity such as has never dawned in their history before. We have made them in the sincere desire to achieve peace ; but beyond them we cannot go. We trust that you will be able to accept them in principle.

I shall be ready to discuss their application in detail whenever your acceptance in principle is communicated to me.

I am,

Yours faithfully,

(Signed) ‘ D. LLOYD GEORGE.

Eamon de Valera, Esq.,

The Mansion House, Dublin.

The Right Hon. David Lloyd George,

10, Downing Street,

Whitehall, London. Mansion House, Dublin,

Sir, August 24, 1921.

‘ The anticipatory judgment I gave in my reply of the 10th August has been confirmed. I laid the proposals of your Government before Dail Eireann, and, by an unanimous vote, it has rejected them.

From your letter of the 13th August it was clear that the principle we were asked to accept was that the ” geographical propinquity” of Ireland to Britain imposed the condition of the subordination of Ireland’s right to Britain’s strategic interests as she conceives them, and that the very length and persistence of the efforts made in the past to compel Ireland’s acquiescence in a foreign domination imposed the condition of acceptance of that domination now. We cannot believe that your Government intended to commit itself to a principle of sheer militarism destructive of international morality and fatal to the world’s peace. If a small nation’s right to independence is forfeit when a more powerful neighbour covets its territory for the military or other advantages it is supposed to confer, there is an end to liberty. No longer can any small nation claim a right to a separate sovereign existence. Holland and Denmark can be made subservient to Germany, Belgium to Germany or to France, Portugal to Spain. If nations that have been forcibly annexed to empires lose thereby their title to independence, there can be for them no rebirth to freedom. In Ireland’s case, to speak of her seceding from a “partnership she has not accepted, or from an allegiance which she has not undertaken to render, is fundamentally false, just as the claim to subordinate her independence to British strategy is fundamentally unjust. To neither can we, as the representatives of the nation, lend countenance.

If our refusal to betray our nation’s honour and the trust that has been reposed in us is to be made an issue of war by Great Britain, we deplore it. We are as conscious of our responsibilities to the living as we are mindful of principle or of our obligations to the heroic dead. We have not sought war, nor do we seek war, but if war be made upon us we must defend ourselves and shall do so, confident that whether our defence be successful, or unsuccessful no body of representative Irishmen or Irishwomen will ever propose to the nation the surrender of its birthright.

We long to end the conflict between Britain and Ireland. If your Government be determined to impose its will upon us by force and, antecedent to negotiation to insist upon conditions that involve a surrender of our whole national position and make negotiation a mockery, the responsibility for the continuance of the conflict rests upon you.

On the basis of the broad guiding principle of government by the consent of the governed, peace can be secured—a peace that will be just and honourable to all, and fruitful of concord and enduring amity. To negotiate such a peace, Dail Eireann is ready to appoint its representatives, and, if your Government accepts the principle proposed, to invest them with plenary powers to meet and arrange with you for its application in detail.

I am, Sir,

Faithfully yours,

(Signed) EAMON DE VALERA.

August 24, 1921.

Sir, 10, Downing Street, London, S.W. 1, Augtist 26, 1921.

The British Government are’ profoundly disappointed by your letter of the 24th August, which was delivered to me yesterday. You write of the conditions of a meeting between us as though no meeting had ever taken place. I must remind you, therefore, that when I asked you to meet me six weeks ago, I made no preliminary conditions of any sort. You came to London on that invitation and exchanged views with me at three meetings of considerable length. The proposals which I made to you after those meetings were based upon full and sympathetic consideration of the views which you expressed. As I have already said, they were not made in any haggling spirit. On the contrary, my colleagues and I went to the very limit of our powers in endeavouring to reconcile British and Irish interests.

Our proposals have gone far beyond all precedent, and have been approved as liberal by the whole civilised world. Even in quarters which have shown a sympathy with the most extreme of Irish claims, they are regarded as the utmost which the Empire can reasonably offer or Ireland reasonably expect. The only criticism of them which I have yet heard outside Ireland is from those who maintain that our proposals have outstepped both warrant and wisdom in their- liberality. Your letter shows no recognition of this, and further negotiations must, I fear, be futile unless some definite progress is made towards acceptance of a basis. You declare that our proposals involve a surrender of Ireland’s whole national position and reduce her to subservience. What are the facts? Under the settlement which we have outlined Ireland would control every nerve and fibre of her national existence; she would speak her own language and make her own religious life; she would have complete power over taxation and finance, subject only to an agreement

for keeping trade and transport as free as possible between herself and Great Britain, her best market; she’ would have uncontrolled authority over education and all the moral and spiritual interests of her race; she would have it also over law and order, over land and agriculture, over the conditions of labour and industry, over the health and homes of her people, and over her own land defence. She would, in fact, within the shores of Ireland, be free in every aspect of national activity, national expression and national development. The States of the American Union, sovereign though they be, enjoy no such range of rights. And our proposals go even further, for they invite Ireland to take her place as a partner in the great commonwealth of free nations united by allegiance to the King.

We consider that these proposals completely fulfil your wish that the principle of ” government by consent of the governed ” should be the broad guiding principleof the settlement which your plenipotentiaries are to negotiate. That principle was first developed in England, and is the mainspring of the representative institutions which she was the first to create. It was spread by her throughout the world, and is now.the very life of the British Commonwealth. We could not have invited the Irish people to take their place in that Commonwealth on any other principle, and we are convinced that through it we can heal the old misunderstandings and achieve an enduring partnership as honourable to Ireland as to the other nations of which the Commonwealth consists. But when you argue that the relations of Ireland with the British Empire are comparable in principle to those of Holland or Belgium with the German Empire,I find it necessary to repeat once more that those are premises which no British Government, whatever its complexion, can ever accept. In demanding that Ireland should be treated as a separate sovereign Power, with no allegiance to the Crown and no loyalty to the sister nations of the Commonwealth, you are advancing claims which the most famous national leaders in Irish history, from Grattan to Parnelland Redmond, have explicitly disowned. Grattan, in a famous phrase, declared that “the ocean protests against separation^ and the sea against union.” Daniel 0’Connell, the most eloquent perhaps of all the spokesmen of the Irish national cause, protested thus in the House of Commons in 1830 :—

” Never did monarch receive more undivided allegiance than the present King from the men who in Ireland agitate the repeal of the Union. Never, too, was there a grosser calumny than to assert that they wish to produce a separation between the two countries. Never was there a greater mistake than to suppose that we wish to dissolve the connection.”

And in a well-known letter to the Duke of Wellington in 1845, Thomas Davis, the fervent exponent of the ideals of Young Ireland, wrote :—

” I do not seek a raw repeal of the Act.of Union. I want you to retain the Imperial Parliament with its Imperial power. I ask you only to disencumber it of those-cares which exhaust its patience and embarrass its attention. I ask you to give Ireland a Senate of some sort, selected by the people, in part or in whole; levying their Customs and Excise and other taxes; making their roads, harbours, railways, canals, and bridges; encouraging their manufactures, commerce, agriculture and fisheries; settling their Poor Laws, their tithes, tenures, grand juries and franchises; giving a vent to ambition, an opportunity for knowledge, restoring the absentees, securing work, and diminishing poverty, crime, ignorance and discontent. This, were I an Englishman, I should ask for England, besides the Imperial Parliament. So would I for Wales, were I a Welshman, and for Scotland, were I a Scotchman; this I ask for Ireland.”

The British Government have offered Ireland all that O’Connell and Thomas Davis asked, and more; and we are met only by an unqualified demand that we should recognise Ireland as a foreign Power. It is playing with phrases to suggest that the principle of government by consent of the governed compels a recognition of that demand on our part, or that in repudiating it we are straining geographical and historical considerations to justify a claim to ascendency over the Irish race.” There is no political principle, however clear, that can be applied without regard to limitations imposed by physical and historical facts. Those limitations are as necessary as the very principle itself to the structure,of every free nation; to deny them would involve the dissolution of all democratic States. It is on these elementary grounds that we have called attention to the governing force of the geographical propinquity of these two islands, and of their long historic association despite great differences of character and race. We do not believe that the permanent reconciliation of Great Britain and Ireland can ever be attained without a recognition of their physical and historical interdependence, which makes complete political and economic separation impracticable for both.

I cannot better express the British standpoint in this respect than in words used of the Northern and Southern States-by Abraham Lincoln in the First Inaugural Address. They were spoken by him on the brink of the American Civil War. which he”was striving to avert:— “Physically speaking” (he said) “we cannot separate. We cannot remove our respective sections from each other, nor build an impassable wall between them. . . . It is impossible, then, to make that intercourse more advantageous or more satisfactory after separation than before. . . . Suppose you go to war, you cannot fight always; and when, after much loss on both sides and no gain on either, you cease fighting, the identical old questions as to terms of intercourse are again upon you.”

I do not think it can be reasonably contended that the relations of Great Britain and Ireland are in any different case. I thought I had made it clear, both in my conversations with you and in my two subsequent communications, that we can discuss no settlement which involves a refusal on the part of Ireland to accept our invitation to free, equal, and loyal partnership in the British Commonwealth under one Sovereign. We are reluctant to precipitate the issue, but we must point out that a prolongation of the present state of affairs is dangerous. Action is being taken in various directions which, if continued, would prejudice the truce and must ultimately lead to its termination.

This would indeed be deplorable. Whilst, therefore, prepared to make every allowance as to time which will advance the cause of peace, we cannot prolong a mere exchange of notes. It is essential that some definite and immediate progress should be made towards a basis upon which further negotiations can usefully proceed. Your letter seems to us unfortunately to show no such progress. In this and my previous letters I have set forth the considerations which must govern the attitude of His Majesty’s Government in any negotiations which they undertake. If you are prepared to examine how far these considerations can be reconciled with the aspirations which you represent, I shall be happy to meet you and your colleagues.

* I am, Sir,

Yours faithfully,

(Signed) D LLOYD GEORGE

Eamon de Valera, Esq.,

Mansion House, Dublin.

XXIII.

Reply received from Mr. de Valera, August 31, 1921.

The Right Hon. David Lloyd George, -.

10, Downing Street,

Whitehall, London. Mansion House, Dublin-,

Sir, -August 30, 1921.

We, too, are convinced that it is essential that some “definite and immediate progress should be made towards a basis upon which further negotiations can usefully proceed,” and recognise the futility of a “mere exchange” of argumentative notes. I shall therefore refrain from commenting on the fallacious historical references in your last communication. The present is the reality with which we have to deal. The conditions to-day are the resultant of the past, accurately summing it up and giving in simplest form the essential data of the problem. These data are:—

1. The people of Ireland, acknowledging no voluntary union with Great Britain, and claiming as a fundamental natural right to choose freely for themselves the path they shall take to realise their national destiny, have, by an overwhelming majority, declared for independence, set up a republic and more than once confirmed their choice.

2. Great Britain, on the other hand, acts as though Ireland were bound to her by a contract of union that forbade separation. The circumstances of the supposed contract are notorious, yet, on the theory of its validity, the British Government and Parliament claim to rule and legislate forIreland, even to the point of partitioning Irish territory against the will of the Irish people, and killing or casting into prison every Irish citizen who refuses allegiance. The proposals of your Government, submitted in the draft of the 20th July, are based fundamentally on the latter premises. We have rejected these proposals, and our rejection is irrevocable. They were not an invitation to Ireland to enter into ” a free and willing” partnership with the free nations of the British Commonwealth. They were an invitation to Ireland to enter in a guise and under conditions which determine a status definitely inferior to that of these free States. Canada, Australia, South Africa, New Zealand are all guaranteed against the domination of the major State, not only by the acknowledged constitutional rights which give them equality of status with Great Britain and absolute freedom from the control of the British Parliament and Government, but by the thousands of miles that separate them from Great Britain. Ireland would have the guarantees neither of distance nor of right.

The condition sought to be imposed would divide her into two artificial States, each destructive of the other’s influence in any common council, and both subject to the military, naval and economic control of the British Government. The main historical and geographical facts are not in dispute, but your Government insists on viewing them from your standpoint. W e must be allowed to view them from “ours.

The history that you interpret as dictating union we read as dictating separation. Our interpretations of the fact of “geographical propinquity” are no less diametrically opposed. We are convinced that ours is the true and just interpretation, and, as a proof, are willing that a neutral, impartial arbitrator should be the judge. You refuse, and threaten to give effect to your view by force. Our reply must be that if you adopt that course we can only resist, as the generations before us have resisted.Force will not solve the problem. It will never secure the ultimate victory over reason and right; If you again resort to force, and if victory be not on the side of justice, the problem that confronts us will confront our successors.

The fact that for 750 years this problem has resisted a solution by force is evidence and warning sufficient. It is true wisdom, therefore, and true statesmanship, not any false idealism, that prompts me and my colleagues. Threats of force must be set aside. They must be set aside from the beginning, as well as during the actual conduct of the negotiations. The respective plenipotentiaries must meet untrammelled by any conditions save the facts themselves, and must be prepared to reconcile their subsequent differences not by appeals to force, covert or open, but by reference to some guiding principle on which there is common agreement. We have proposed the principle of government by the consent of the governed, and do not mean it as a mere phrase. It is a simple expression of the test to which any proposed solution must respond if it is to prove adequate, and it can be used as a criterion for the details as well as for the whole. That you claim as a peculiarly British principle, instituted by Britain, and ” now the verv life of the British Commonwealth ” should make it peculiarly acceptable to you. On this basis and this only we see a hope of reconciling “the considerations which must govern the attitude” of Britain’s representatives with the considerations that must govern the attitude of Ireland’s representatives,’ and on this basis we are ready at once to appoint plenipotentiaries.

I am, Sir,

Faithfullv. yours,

(Signed) EAMON DE VALERA.

XXIV .

The Prime Minister Reply to Mr. de Valera’s Letter of

August 30, 1921.

Sir, Town Hall, Inverness, September 7, 1921.

His Majesty’s Government have considered your letter of the 30th August, and have to make the following observations upon it : — The principle of government by consent of the governed is the foundation of British constitutional development, but we cannot accept as a basis of practical conference an interpretation of that principle which wrould commit us to any demands which you might present—even to the extent of setting up a Republic and repudiating the Crown. You must be aware that conference on such a basis is impossible. So applied, the principle of government by consent of the governed would undermine the fabric of every democratic State and drive the civilised world back into tribalism.

On the other hand, we have invited you to discuss our proposals on their merits,in order that you may have no doubt as to the scope and sincerity of our intentions. It would be open to you in such a conference to raise the subject of guarantees on any points in which you may consider Irish freedom prejudiced by these proposals. ‘His Majesty’s Government are loth to believe that you will insist upon rejecting their proposals without examining them in conference. To decline to discuss a settlement which would bestow upon the Irish people the fullest freedom of national development within the Empire can only mean that you repudiate all allegiance to the Crown and all membership of the British Commonwealth. If we were to draw this inference from your letter, then further discussion between us could serve no useful purpose, and all conference would be vain. If, however, we are mistaken in this inference, as we still hope, and if your real objection to our proposals is that they offer Ireland less than the liberty which we have described, that objection can be explored at a conference.

You will agree that this correspondence has lasted long enough. His Majesty’s Government must, therefore, ask for a definite reply as to whether you are preparedto enter a conference to ascertain how the association of Ireland with the community of nations known as the British Empire can best be reconciled with Irish national aspirations. If, as we hope, your answer is in the affirmative, I suggest that the conference should meet at Inverness on the 20th instant.

I am, Sir,

Yours faithfully,

(Signed) D. LLOYD GEORGE.

Eamon de Valera, Esq.,

Mansion House, Dublin.

XXV.

Reply received from Mr. de Valera, September 13, 1921.

(Official Translation.)

The Right. Hon. David Lloyd George,

10, Downing Street,

Whitehall, London. Mansion House, Dublin,

Sir, September 12; 1921.

We have no hesitation in declaring our willingness to enter a conference to ascertain how the association of Ireland with the community of nations known as the British Empire can best be reconciled with Irish national aspirations. Our readiness to contemplate such an association was indicated in our letter of the 10th August. We have accordingly summoned Dail Eireann that we may submit to it for ratification the names of the representatives it is our intention to propose.

We hope that these representatives will find it possible to be at Inverness on the date you suggest, the 20th September. In this final note we deem it our duty to reaffirm that our position is and can only be as we have defined it throughout this correspondence. Our nation has formally declared its independence and recognises itself as a sovereign State. It is only as the representatives of that State and as its chosen guardians that we have any authority or powers to act on behalf of our people. As regards the principle of ” government by consent of the governed,” in the very nature of things it must be the basis of any agreement that will achieve the

purpose, we have at heart, that is, tbe final reconciliation of our nation with yours. We have suggested no interpretation of that principle save its every day inter pretation— the sense, for example, in which it was, understood by the plain men and women of the world when on the 5th January, 1918, you said :— ” The settlement of the New Europe must be based on such grounds of reason and justice as will give some promise of stability. Therefore it is that we feel that government with the consent of the governed must be the basis of any territorial settlement in this war.”

These words are the true answer to the criticism of our position which your last letter puts forward. The principle was understood then to mean the right of nations that had been annexed to empires against their will to free themselves from the. grappling hook. That is the sense in which we understood it. In reality it is your Government, when it seeks to rend our ancient nation and to partition its territory, that would give to the principle an interpretation that ” would undermine the fabric of every democratic State, and drive the civilised world back into tribalism.”

(Signed) EAMON DE VALERA.

(Telegraphed.)

“Sir, ‘ : September 15, 1921.

I informed your emissaries who came to me here on Tuesday, the 13th, that the reiteration of your claim to negotiate with His Majesty’s Government as the representafives of an independent and sovereign State would make conference between us impossible. They brought me a letter from you in which you specifically reaffirm that claim, stating that your nation “has formally declared its independence and recognises itself as a sovereign State,” and ” it is only,” you added, ” as the representatives of that State, and as its chosen guardians, that we have any authority or powers to act on behalf of our people.” I asked them to warn you of the very serious effects of such a paragraph, and I offered to regard the letter as undelivered to me in order that you might have time to reconsider it. Despite this intimation, you have now published the letter in its original form. I must accordingly cancel the arrangements for conference next week at Inverness, and must consult my colleagues on the course of action which this new situation necessitates. I will communicate this to you as soon as possible, but, as I am for the moment laid up here, a few days’ delay is inevitable

Meanwhile, I must make it absolutely clear that His Majesty’s Government cannot reconsider the position which I have stated to you. If we accepted conference with your delegates on a formal statement of the claim which you have reaffirmed, it would constitute an official recognition by His Majesty’s Government of the severance of Ireland from the Empire and of its existence as an independent Republic. It would, moreover, entitle you to declare as of right acknowledged by us that in preference to association with the British Empire you would pursue a closer association by treaty with some foreign Power. There is only one answer possible to such a claim as that.

The great concessions which His Majesty’s Government have made to the feeling of your people in order to secure a lasting settlement deserve, in my opinion, some more generous response, but, so far, every advance has been made by us.

On your part you have not come to meet us by a single step, but have merely reiterated in phrases of emphatic challenge the letter and spirit of your, original claim.

I am,

Yours faithfully,

(Signed) D. LLOYD GEORGE.

XXVII.

Reply received from Mr. de Valera, September 16, 1921.

(Telegraphed.)

The Right Hon. D. Lloyd George

-Sir, ” September 16, 1921.

I received you telegram last night.. I am surprised that you do not see that if we on our side accepted the conference on the basis of your letter of the 7th September without making our position equally clear, Ireland’s representatives would enter the conference with their position misunderstood and the cause of Ireland’s right irreparably prejudiced. Throughout the correspondence that has taken place you have defined your Governments position. We have defined ours. If the positions were not so definitely opposed there would indeed be no problem to discuss. It should be obvious that in a case like this if there is to be any result the negotiators must meet without prejudice and untrammelled by any conditions whatsoever, except those imposed by the facts as they know them.

(Signed) EAMON DE VALERA.

September 16, 1921.

(Telegraphed.)

Sir, Gairloch, September 17, 1921.