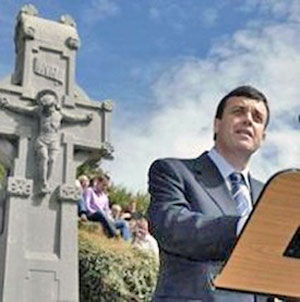

Brian Lenihan TD

Béal na Bláth, Sunday 22 August 2010

Brian Lenihan TD Minister for Finance

First, may I say how great an honour it is to be invited to speak at this annual commemoration of the life and legacy of Michael Collins. When the generous and quite unexpected offer of the Collins family and the Commemoration Committee was conveyed to me I was delighted to accept.

I am acutely conscious that while in recent years there has been a range of speakers at this event, this is the first time someone from the Fianna Fail party, has been given this privilege. It is true that over time the painful divisions from which emerged the two largest political parties in the State have more or less entirely healed. The differences between Fianna Fail and Fine Gael today are no longer defined by the Civil War, nor have they been for many years. It would be absurd if they were. This period of our history is gradually moving out of living memory. We ask and expect those in Northern Ireland to live and work together despite the carnage and grief of a much more recent, and much more protracted, conflict.

Nonetheless, keen competition between Fianna Fail and Fine Gael remains – as I am very aware every time I stand up in the Dail. But the power of symbolism cannot be denied, all the more so as we move towards the centenaries of the Easter Rising and all that followed. If today’s commemoration can be seen as a further public act of historical reconciliation, at one of Irish history’s sacred places, then I will be proud to have played my part.

Today is a day to recall the remarkable qualities of a man who, along with O’Connell, Parnell and De Valera, is part of our national Pantheon. As Dr Garret FitzGerald has written, these other three political leaders “had not only the capacity and ability to play a major political role over an extended period of time, but also the opportunity to do so.” Dr FitzGerald adds: “There are others who if they had lived. . …might have rivalled or even outshone some or all of these three – most notably Michael Collins in this century.”

Fine Gael has of course been the political custodian of the memory of Michael Collins, including at a time when some in Fianna Fail were unwilling to recognise his importance and to salute his greatness. It may be that De Valera himself felt a sense of challenge from the ghost of Collins. Political partisanship led to their followers championing one or the other.

But, not withstanding the very real polarisation in the post-Civil War period, there was more fluidity in the early decades of our politics than is often recalled. My own paternal grandfather, Paddy Lenihan, greatly admired Michael Collins and took the pro-treaty side in 1922. Indeed, he referred to this fact when he was a Fianna Fail backbencher in the Dail in 1969. Speaking during a debate on the eruption of the Troubles in the North he recalled that when he was a young university student in Galway during the Truce, Collins called for Volunteers to invade the North. “I remember putting my name to it,” he told the House. “It was rather stupid when one thinks of it. These were the things done in those days but 1969 is a different day. ….I appeal to young men to keep sane about these things, to catch themselves on”.

Years after the Civil War, after a decade as a civil servant, my grandfather joined Fianna Fail, attracted in particular by Sean Lemass who shared many of the same qualities he had admired in Michael Collins: the talent for organisation, great energy and a modernising tendency.

I should add that my maternal grandfather, Joe Devine, having been in the IRA during the War of Independence, immediately joined An Garda Siochana on its formation in 1922 and loyally served the State, under governments of several different complexions, for many decades.

De Valera’s reputation may have suffered from the fact that he stayed on too long as Taoiseach and leader of his party. But so much of our thinking about Collins is dominated by questions whose answers we will never know. One of the many imponderables that arise from his untimely death is the impact he would have had on the politics of the new State of which he had been a key architect. No man is fully formed at the age of 31 . Had Collins lived, would the Civil War have ended sooner and would its legacy have been less bitter? What kind of leader would he have become and what would have been the shape of the political party he would have fashioned? Would the party to which I belong have been pre-empted by the party he would have created? How would he have approached Northern Ireland and relations with Britain?

There are tantalizing questions. As Professor Joe Lee has written: ,,Almost any answer is plausible, depending on one’s assumptions”. Indeed professor Lee rightly urges students of Collins to spell out explicitly those assumptions so that debate can take place on a proper historical plane and can be rescued from the purposes of propagandists.

In recent decades, however, the full magnitude of Collins’s achievements has, I believe, come to be appreciated and valued by Irishmen and women right across the political spectrum. But at times this has, regrettably and unnecessarily, been accompanied by a denigration of Eamon De Valera, as if only one of the two could win the approbation of history.

But even if we can never know how the relationship between Collins and DeValera might have evolved, surely now we have the maturity to see that, in their very different styles, both made huge contributions to the creation and development of our State.

They shared much, in terms of their devotion to lreland, their interest in its language and culture, their piety, their social conservatism. While in some ways they were temperamental opposites, nonetheless each was quickly identified by his peers as a natural leader. Neither was without flaws, but each had great strengths. Each was, at different periods, prepared to operate within the constraints of the realities facing him, without losing sight of his greater vision of a free, prosperous, distinctive and united Ireland.

It is also true that part of the healing process on our island must be an acknowledgement, aided by the work of modern historians like T Ryle Dwyer and the late Peter Hart, that, alongside great patriotism and self-sacrifice, terrible deeds were done on all sides during the War of Independence and the Civil War. We cannot know today how we as individuals might have thought or acted in those convulsive years. Nor must we forget that many people with little or no connection to the struggle died or suffered by accident, or because of where they worked or where they worshipped.

In the round, however, the generation which laid and built on the foundations of our modem state achieved remarkable things. Collins stood at the very forefront of that generation, and his qualities were remarkable.

Collins was a man of energy and action;

An astute politician:

A man of extraordinary organisational and administrative ability;

A pragmatist who believed he could over time bring Ireland total independence;

A driven, ambitious man who was born to be a leader.

I have been re-reading some of the Collins biographies and historical analyses of his career. You will forgive me ifl have taken a particular interest in his work as Minister for Finance between 1919 and 1922.1n a meeting room in the Department of Finance where I have spent many hours over the last two years, hang pictures of all previous Ministers. They are in sequence. Eoin McNeill’s portrait is the first because he was actually the first to hold that office in the First Dail, though he served for less than ten weeks. The picture of Collins is placed second and regularly catches my eye: he is the youngest and, I daresay, the best looking of us all.

It was Michael Collins who set up in its basic form a system of financial administration, important elements of which persist to this day. Of course, it was the task of raising the loan to finance the work of the revolutionary government that preoccupied him most as Minister for Finance. History has recorded the extraordinary success of that venture in the most adverse circumstances of suppression and constant hindrance by the British authorities. It was a truly remarkable feat and it added greatly to the authority and capacity of the first Dail at home and abroad.

What is less often recognised is Collins’s work in putting in place an accounting system that required government departments to give full reports of expenditure to the Dail, and also required that any financial proposal brought to Cabinet should be first submitted to the Minister for Finance. Here was a man at constant risk of arrest and death, running a ruthless guerrilla war and masterminding the highl efficient intelligence system which secured its success. Yet he still had the time and the ability to build the foundations of a system of financial control. He recognised that such a system was essential to the running of a State. His talent for state-craft was also evident when in the period between the signing of the Treaty and the outbreak of the Civil War he continued to build the administrative apparatus which still serves the modem Irish State.

There is no substantive connection between the economic and financial position we confront today and the totally different challenge faced by Collins and his contemporaries. But as I look at those pictures of my predecessors on the wall in my meeting room I recognise that many of them, from Collins through to Ray McSharry, had in their time to deal with immense, if different, difftculties. I am comforted by what their stories tell me about the essential resilience of our country of our political and administrative system, and above all of the Irish people. That is why I am convinced that we have the ability to work though and to overcome our present difficulties, great though the scale of the challenges may be and devastating though the effects of the crisis have been on the lives of so many of our citizens.

The resolution of the current economic and financial crisis is the key challenge for this generation. The depth of the crisis, and the scale of its human cost has inevitably given rise to sharp and, of course entirely legitimate disagreement between political parties and between individual commentators about how it can be resolved. Very few of even the most eminent economic experts, domestically. within the European Union, or internationally, foresaw the speed and extent of the crisis, either here in Ireland or worldwide. By the same token, none of us should be dogmatic in our certainties. I hope that we can all accept that ow differing approaches and viewpoints do not call into question our sincerity and good faith.

But we must be resolute in our determination to do what is right. Those of us in government have to make decisions in real time based on the best information and advice available to us.

We know we must address the severe difficulties we face with a sense of realism and an awareness of the international environment in which we work. Whatever our disagreernents, I believe we can and must all work together to build a viable economy which can sustain jobs for all our people, We need a national understanding and acceptance that three elements are essential to the recovery and maintenance of future employment:

1. We must improve our competitiveness

2. We must restore sustainable public finances

3. We must ensure that credit is available for businesses and households

In a small open economy like ours, competitiveness is essential to creating sustainable jobs. We know from our own and from international experience that only the private sector can create enough good jobs to meet the demands ofour highly-trained young people and to solve the unemployment problem. We need businesses to compete successfully in the global marketplace so that they will expand employment to meet increased demand for their goods and services. Last year, we recorded a significant improvernent in competitiveness relative to the rest of the eurozone. This helped to keep our exports constant while those of many other countries slurnped. We must build on this improvement in competitiveness in the coming years, throughout all sectors of the economy. That means that costs must be kept under control and reduced wherever possible, especially relative to our European partners. But we must also continue to invest in infrastructure, in research and in education, as the Government is committed to do.

Job creation requires that the public finances be put back on a sustainable path. We know from the 1980s that unless businesses are confident about the Exchequer’s long term position, they will not create new jobs. What we spend on our public services must be funded by an efficient tax system. In the medium term rve cannot borrow to fund day to day services. As I made clear last Decernber, I am committed to delivering budgets for 2011 and 2012 which continue to bring expenditure and revenues towards a sustainable balance. It is also now abundantly clear – as the pressures on the Ewozone this year have made manifest – that neither the bond markets, nor our major EU partners, would tolerate any slippage on our part. So far, they are confident that we will keep to the path we have mapped out.

This inevitably means that the next budgets will continue to require strict control of expenditure. What I can promise is that as Minister I will try to ensure that the burden is borne by those who can best afford iL Recent budgets have, according to the ESRI’ made a positive contribution towards a fairer tax systern’ The budgetary measures have been progressive: those who can afford to pay the most, are paying the most.

Credit must be available to businesses that want to invest and createjobs. To provide such credit banks must attract funding which they can then lend on to these sustainable businesses. The measures adopted to resolve the banking crisis, including the creation of NAMA and support for individual financial institutions, are grormded in realism’ Some elements of these measures have received the support of other political parties. Some have not. I have welcomed the approval of alt parties for the appointments of Professor Patrick Honohan as Govenor of the Central Bank and Matthew Elderfield as Financial Regulator. In advancing solutions to our economic crisis we must listen to these acknowledged experts and other experts to ensure our solutions are realistic. Their expertise cannot be dismissed just because it points the way to rigorous and difficult solutions.

I appreciate and understand continuing public incomprehension and anger at the scale of the funding necessary to rescue the banking sector – above all the vast sums being channelled into Anglo-Irish Bank. Fury is a quite reasonable response to the incredible recklessness and incompetence which fuelled the banking mania of the last Celtic Tiger years. Like others I hope that anyone who broke the law will face its full rigours. But anger is not a policy on its own. The Government has made the difficult decision to support the banks based on the expert advice available to us here at home and also from the EU and IMF. That advice has strongly been that we must stand behind our banks in order to ensure that a sustainable financial system is established and, in the case of Anglo, to ensure that the resolution of its debts does not damage Ireland’s international credit-worthiness and end up costing us even more than we must now pay.

The successful resolution of the three key challenges – competitiveness, the public finances, and the supply of credit – requires that all those in positions of leadership be straight with the people. Solutions that would make Ireland an international pariah, walking away from our financial commitrnents or from our EU obligations, are just not credible. We must be realistic in our approach to this crisis. Collins and the founders of this State were determined that all citizens should have equal rights and equal opportunities. The job of government is to strike a balance between the legitimate interests of individual groups and the greater good. Sometimes, and quite frequently in times of economic difficulty, achieving this balance requires governments to take unpopular decisions. But that is what leadership in a democracy is about: the exercise of power in the interests of the common good. Governments must face up to realities and act; to procrastinate and hope that problems solve themselves is not an option.

Over the last two years our country has been severely shaken. But our economy is beginning to heal. Exports are growing and consumer spending has moved off its lows of late last year. New order books are expanding and business confidence has improved markedly. Most forecasters now expect Ireland to register the strongest pace of economic growth in the eurozone next year. Tax revenues are stabilising and our underlying budget deficit will shrink next year.

As in other countries, our recovery is likely to be somewhat uneven’ And it is a very unfortunate reality that a reduction in unemployment will’ as is usually the case internationally, lag behind other indicators. But let there be no doubt that if we continue to make progress in the three key areas – improved competitiveness, sustainable public finances, and the proper availability of credit – we will return to high employment levels and maintain an average standard of living that is still among the highest in the world’

The challenges we face today are different from those that confronted previous generations since the foundation of this State. But we need to remind ourselves that many of those challenges were as daunting as our own.

In the 1920s, the apparatus of the state was created in the face of conflict and political division. In the 1930s, the first economic enterprises of the State were established in the face of the most severe global economic downturn ever. In the 1940s, the State survived and protected its citizens throughout the greatest conflict in history. In the 1960s, the State began the transformation from an agrarian economy and society to a more balanced modern economy and society. The 1970s saw an opening up of Ireland to the world and the extensive further modernising steps which that required. The 1980s saw a more severe unemployment crisis than the one we face today, and we overcame that through the resiiience of our people and our investment in education. The benefit of this transformation was seen through the 1990s and the start of this decade with Ireland experiencing one of the most sustained and remarkable economic expansions in recent history.

Yes, the current crisis is deep and severe. But we have surmounted similar difficulties in the past.

In meeting challenges and seizing opportunities, the lrish people have shown their courage, determination and creativity -just as Michael Collins and his comrades and colleagues did in the campaign for independence and in the establishment of our State.

The spirit of Collins is the spirit of our nation, and it must continue to inspire all of us in public life, irrespective of party or tradition.