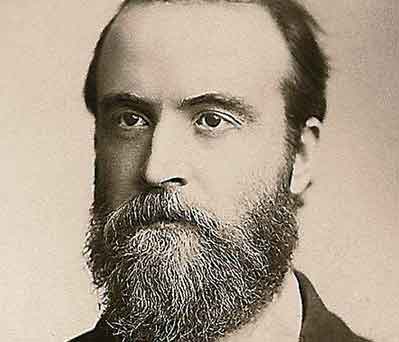

Charles Stewart Parnell

Parnell was a protestant landlord whose family estate was at Avondale, Co. Wicklow. He was first elected to parliament in the Meath by-election of April 1875 and joined the Home Rule Party led by Isaac Butt. Parnell was only twenty-nine when he entered parliament. His mother, Delia Stewart, was American. He received most of his education in England, and later on fell in love with an English woman, Mrs. O’Shea. Yet he appeared to despise everything English. Parnell, on entering parliament, found that he could give vent to his anti-English feelings by joining Joseph Biggar in obstructing the work of the House of Commons. They did this by making extremely long and boring speeches on any matter which lay before the House. The obstructionists attracted support in Ireland and in Fenian circles and as they became more popular the prestige of Butt decreased.

Parnell was a protestant landlord whose family estate was at Avondale, Co. Wicklow. He was first elected to parliament in the Meath by-election of April 1875 and joined the Home Rule Party led by Isaac Butt. Parnell was only twenty-nine when he entered parliament. His mother, Delia Stewart, was American. He received most of his education in England, and later on fell in love with an English woman, Mrs. O’Shea. Yet he appeared to despise everything English. Parnell, on entering parliament, found that he could give vent to his anti-English feelings by joining Joseph Biggar in obstructing the work of the House of Commons. They did this by making extremely long and boring speeches on any matter which lay before the House. The obstructionists attracted support in Ireland and in Fenian circles and as they became more popular the prestige of Butt decreased.

On 21 October 1879, Davitt founded the Irish National Land League in Dublin with Parnell as President. The main objectives of the League were to provide tenants with a fair rent, fixed tenure and free sale. The long term aim was that farmers would own the land (peasant proprietorship). The Land League became a hugely popular movement overnight. The Land League taught the Irish farmers to stand on their own feet and assert their rights. Gladstone became Prime Minister for the second time in April 1880 and hoped to pass an emergency Land Bill through parliament that summer. When he was defeated in the House of Lords, the Land League took law into its own hands.

Speaking at Ennis on 19 September 1880, Parnell declared : “When a man takes a farm from which another had been evicted you must shun him on the roadside when you meet him, you must shun him in the streets of the town, you must shun him in the shop, you must shun him in the fairgreen and in the marketplace, and even in the place of worship, by leaving him alone, by putting him in a moral Coventry, by isolating him from the rest of his country as if he were the leper of old, you must show your detestation of the crime he has committed”. This type of “moral Coventry” was used in the cast of Captain Boycott, a County Mayo land agent, who was isolated by the local people until his nerve broke. This led to a new word entering in to the English language, boycotting.

Parnell became the accepted leader of the Irish nationalist movement during the years 1880-1882. He was referred to as the “Uncrowned King of Ireland”. Parnell received considerable financial support from America which he used to channel funds into the Irish Parliamentary Party. (Parnell went to America in 1880 with John Dillon and collected more than 26,000 pounds). Unrest about the Land Question erupted at times into violence. The British government passed a new Coercion Act. Parnell and other leaders were arrested in October 1881 and the League was put down. Gladstone came to terms with Parnell in March 1882 with the “Kilmainham Treaty”, (Parnell was at this time in Kilmainham Jail). The prisoners were released, the agitation about the land question was discontinued and the policy of land reform begun with the Land Act of 1881 continued. On the release of Parnell, Lord Frederick Cavendish was sent to Ireland as chief secretary to begin a new era of peace, but on the day he arrived, he and his under-secretary, Burke, were murdered in the Phoenix Park by members of a secret society, the Invincibles. Parnell condemned the murders and despite the setback Gladstone’s attitude to Parnell and the Home Rule question remained basically unchanged. Parnell always believed that solving the Land Question should be the first step on the road to Home Rule. In December 1882, when the suppressed Land League was replaced by the Irish National League, he ensured that the new organisation was under the control of his party and that its primary objective was the winning of Home Rule. By 1884, Parnell’s authority was so secure that he was able to impose a party pledge. He managed to unite the party into a single unit under his own command and finally overcame one of Issac Butt’s greatest difficulties.

The general election of 1885 was a huge success for Parnell. His party won every seat outside eastern Ulster and Dublin University. Gladstone, who had won a victory for the Liberals in England, convinced by Parnell’s success and gave the Home Rule Movement his support for the rest of his career. The Home Rule Bill of 1886 met with fierce opposition from the Conservatives who saw it as a betrayal of empire and of the loyalist and Protestant elements of Ireland. Gladstone lost office in the general election of 1186, the first in Britain to be fought on the Home Rule question. This marked a turning point in British relations with Ireland, as for the first time a major political party had committed itself to granting at least a measure of self-government to Ireland.

In 1887, the Times of London published a series of articles, “Parnellism and Crime”, in which the Home Rule leaders were accused of being involved in murder and outrage during the land war. The Times, produced a number of facsimile letters, allegedly bearing Parnell’s signature and in one of the letters Parnell had excused and condoned the murder of T.H. Burke in the Phoenix Park which he had publicly condemned. Parnell immediately declared the letter a forgery and the government set up a Special Commission to investigate the charges made against Parnell and his party. The commission sat for nearly two years. In February 1889, one of the witnesses admitted to having forged the letters; he then fled to Madrid, where he shot himself. Parnell’s name was fully cleared and the Times paid a large sum of money by way of compensation. The closing months of 1889 marked the high point of Parnell’s popularity. He received a standing ovation in the House of Commons, was presented with the freedom of the city of Edinburgh, and stayed as Gladstone’s guest at Hawarden.

In 1887, the Times of London published a series of articles, “Parnellism and Crime”, in which the Home Rule leaders were accused of being involved in murder and outrage during the land war. The Times, produced a number of facsimile letters, allegedly bearing Parnell’s signature and in one of the letters Parnell had excused and condoned the murder of T.H. Burke in the Phoenix Park which he had publicly condemned. Parnell immediately declared the letter a forgery and the government set up a Special Commission to investigate the charges made against Parnell and his party. The commission sat for nearly two years. In February 1889, one of the witnesses admitted to having forged the letters; he then fled to Madrid, where he shot himself. Parnell’s name was fully cleared and the Times paid a large sum of money by way of compensation. The closing months of 1889 marked the high point of Parnell’s popularity. He received a standing ovation in the House of Commons, was presented with the freedom of the city of Edinburgh, and stayed as Gladstone’s guest at Hawarden.

This was the summit of Parnell’s career but a much more serious threat to Parnell’s career was to follow. In December 1889, Captain O’Shea, filed for divorce from his wife, and Parnell was name d in the proceedings. Parnell did not defend himself and to most people it appeared to be another trumped-up charge. This time, however, Parnell was not innocent. He and Mrs. Katherine O’Shea had fallen in love when they first met in 1880. By that time her marriage to Captain O’Shea was breaking down. From 1886, Parnell and Katherine O’Shea lived together. There is no doubt that Captain O’Shea had been aware of Parnell’s relationship with his wife. To keep him happy Parnell had O’Shea elected as an unpledged Home Ruler to the Galway City seat in February 1886, despite opposition from his party. It is not clear why O’Shea delayed until December 1889 before seeking a divorce. One possible reason was the hope of obtaining a large sum of money from his wife, when her aunt, Mrs. Woods, died. Mrs. Woods left her entire fortune to Katherine, but in such a way that her husband could not get his hands on it. Captain O’Shea is said to have resorted to blackmail, asking for 20,000 pounds from his wife but she refused to pay. It was after this that he went ahead with the divorce case.

The divorce case caused a sensation in England and Ireland. On all sides there was a belief that the Irish leader would retire from public life, at least for a short time. Parnell, a proud man, showed no intention of retiring. His refusal to step down produced a bitter spilt in the party. A meeting of the Irish Parliamentary Party was held during the first week of December 1890. After a long discussion as to whether the man (Parnell) was more important than the cause (Home Rule), the party split in two. Forty four members sided with Justin McCarthy, the vice-chairman, and remained in favour of the alliance with the Liberals, and twenty seven sided with Parnell. Parnell had now lost the leadership of the parliamentary party. He refused to accept the verdict given against him. He carried his campaign to Ireland and throughout 1891 fought three by-elections. In all three by-elections, Parnell’s candidate was defeated. As far as Parnell was concerned it was a “war to the death” although he suffered a lot of indignity such as mud-throwing, personal abuse, etc. In June 1891, he married Katherine O’Shea but still refused to retire from public life. Eventually the strain of addressing meetings up and down the country proved too much for him. On 6 October 1891, he died at Brighton. He was only forty-five years of age.

Parnell was the architect of his own downfall. He refused to co-operate with the party during the critical time of the divorce dispute. His attitude was that of a “loner” and so he was prepared to ignore the advice of his best friends. Despite this his achievements were real and lasting. He brought Home Rule from being a faint hope to the forefront of national politics. Both the English political parties and successive governments had to recognise the importance of the Irish question and declare their standpoint on it. The land question had not yet been solved but Parnell’s involvement in it during the years 1879-1882 was a vital factor and he helped future reforms to get underway. By his creation of a disciplined party, he proved that Irishmen were capable of ruling themselves.