Michael Collins and the 1916 Rising

Research, James Langton

Michael Collins is widely remembered today for the significant role he played during the Irish War of Independence. His abilities then as director of intelligence, president of the IRB and Minister of Finance to name but a few have all been documented in the extraordinary amount of books and articles that have been written about him since his untimely death in 1922. However, these stories tend to overshadow other aspects of his short life which include the part he played in the Easter Rising of 1916. Although some historians have previously described his role in the rebellion as a minor one, evidence today suggests otherwise. The following account will therefore focus on his life from the time he left London to take part in the Rising until his subsequent release from Frongoch Prison in Wales.

Sometime around 15 January 1916, Michael Collins along with other members of the IRB left London after being summoned by Sean Mac Diarmiada to return to Ireland. Before he departed he secured release form his employment by telling his manager that he wished to go to Dublin to ‘sign up’ in an Irish regiment. His manager however assumed that Michael was seeking leave to join the British army in order to go fight in the Great War that was raging across Europe at that time. After warmly congratulating him on his decision, his boss allowed him to leave immediately, paying him an extra month’s salary to enable him to take a holiday before he went away. He later changed the cheque for gold in the Bank of England, and on arriving in Dublin handed it over to Sean Mac Diarmuida.

Sometime around 15 January 1916, Michael Collins along with other members of the IRB left London after being summoned by Sean Mac Diarmiada to return to Ireland. Before he departed he secured release form his employment by telling his manager that he wished to go to Dublin to ‘sign up’ in an Irish regiment. His manager however assumed that Michael was seeking leave to join the British army in order to go fight in the Great War that was raging across Europe at that time. After warmly congratulating him on his decision, his boss allowed him to leave immediately, paying him an extra month’s salary to enable him to take a holiday before he went away. He later changed the cheque for gold in the Bank of England, and on arriving in Dublin handed it over to Sean Mac Diarmuida.

Through Mac Diarmuida he obtained part-time employment working three days a week as financial advisor to Count Plunkett who resided in Kimmage on the outskirts of Dublin city. With its extensive grounds, Count Plunkett allowed it to be used as a training area for the newly formed Irish Volunteers, especially those who had returned from London in a bid to avoid conscription. As April approached and plans for an uprising were being finalised, Michael also worked very closely with Sean Mac Diarmiada. Nancy O’Brien had met them both during Easter week. In fact, both men openly discussed details of the rebellion in front of her while having tea and buns in a Dublin Café. That Saturday, Nancy bumped into Michael again and they talked briefly in Sackville Street (now O’Connell Street) before they bid farewell to each other on the bridge. She had originally planned to go home to Sams Cross for the Easter, but her transfer to the GPO had come through and she was due to report there for work the following Tuesday. When she informed Michael of this, he simply quipped “you might have a rather long wait”. She would later recall that this thought was uppermost in her mind the following week as she watched the progress of the insurrection from the vicinity of Howth Head. Other people who had met Michael during the week leading up to the Rising described him as being ‘jocular and fooling about as usual’.

Although he was working in the Plunkett home at Kimmage and also a member of the Irish Volunteers, an impressed Joe Plunkett put Collins on his staff and they both got on very well together exchanging books and ideas. Collins it was said was very good to the sickly Joe who was seriously ill with tuberculosis. Michael also sometimes acted as bodyguard for both Joe and Sean Mac Diarmiada at this time. Sean was the most active and effective IRB organiser throughout the whole of Ireland and a prime mover in the Irish Volunteers. Every day, Collins would leave Larkfield in Kimmage to collect letters from Plunkett who was in a nursing home and deliver them to the other members of the military council.

Joe had slept every night in that nursing home until that Friday when his aide-de-camp, Michael Collins, brought him and his luggage to the Metropole Hotel on O’Connell Street. On Easter Monday 24 April 1916, Commandant Brennan Whitmore was appointed to Joseph Plunkett’s staff by Thomas MacDonagh to help Michael Collins bring him from the nursing home to Liberty Hall. Before leaving, Collins helped Plunkett into his tunic and called a cab to take them to his previously rented room in the Metropole Hotel. When they arrived Plunkett had to rest again, and then he took maps, books and three revolvers from his trunk and as they were leaving he said to Collins, “You lead out and down the stairs, I and the Commandant will follow. We must not allow ourselves to be arrested under any circumstances. If necessary we must shoot our way out, but not unless it’s necessary. There is an intelligence officer in the vestibule, a stout dark man. If he attempts to interfere he is to be shot at once”. However, as they arrived at the bottom of the stairs the stout dark man just simply bid them good day.

When they arrived at Liberty Hall it was alive with activity, and as Plunkett got out of the cab he was greeted with salutes which he returned with smiles as Michael Collins helped him up the steps towards the main door. Once inside Plunkett received a warm welcome from Pearse and Connolly. Just before noon that day the whole column left Liberty Hall with James Connolly at the head, Padraig Pearse on his right and Joseph Plunkett on his left. Although some left to take up different positions around the city, the main body turned left up Abbey Street and on into O’Connell Street where they halted outside the GPO. Here, Michael Collins stood alongside Plunkett, Pearse, Connolly, Clarke and MacDiarmiada. Then James Connolly gave the order to charge and the men rushed in and stormed the building. A constable of the DMP was quickly disarmed and the counter clerks and customers were ejected from the building. Windows on the ground floor were then smashed and barricaded and shortly after mid-day the seizure of the building was complete. One of the flags that was hoisted on the roof of the GPO that day was a Tri-Colour by the youngest officer present, Gearóid O’ Sullivan, Michael’s cousin. Shortly after, Padraig Pearse emerged from the building and began to read the Proclamation. Michael Collins stood immediately behind him as he did so, scanning the street carefully while his Commander-in Chief read the Proclamation to the end. When they went back inside the GPO, Michael carried out an intensive search of the building, checking provisions and stores that might come in useful for the siege ahead. When he discovered two tierces of porter, he had the alcohol poured down the drain while explaining to those present, “They said we were drunk in ’98, but they won’t be able to say that now”. Then he helped to tie up a captured British officer, Lieutenant A.D. Chalmers of the 14th Royal Fussiliers. “Don’t worry Michael reassured the terrified officer as he bundled him into one of the telephone kiosks, we don’t shoot prisoners”.

As the rebels secured other posts throughout the city and word of the insurrection spread, government forces were brought into action. In the early hours of Tuesday morning 800 infantry troops from the Curragh and 150 troops from Belfast were galvanised into action. Within twenty-four hours after the Rising had started, 3500 troops and the gunboat Helga were poised for action against a force of 1200 insurgents. During that terrible week Michael frequently showed himself resourceful and resolute under fire. His courage was cool and calculating rather than reckless. He had a calming effect on his comrades and an inner strength that communicated itself to them. His cheerful good humour never once deserted him, even when the carnage and destruction seemed appalling, where he quipped to one Volunteer “Don’t worry ye old cod, we’ll rebuild it, and the whole city, in ten years if necessary”.

Michael himself would later recall: Although I was never actually scared in the GPO, I was, and others also witless enough to do the most stupid things. As the flames and heat increased, so apparently did the shelling. Machine-gun fire made escape more and more impossible. Not that we wished to escape. No man wished to budge. In that building, the defiance of our men, and the gallantry reached unimaginable proportions.

However, his name does not emerge again until Tuesday morning when a squabble broke out in the GPO between the London Irish and Desmond Fitzgerald who was in charge of the commissary and refusing them rations on the basis that they didn’t have the requisite documentation. Desmond recalled what happened next:

Michael Collins… strolled in one morning with some of his men who were covered with dust and had been demolishing walls and building barricades, and announced that these men were to be fed if it took the last food in the place. I did not attempt to argue with him, and these men sat down openly rejoicing that I had been crushed… but while they were eating, those of our most regular and assiduous customers who appeared at the door of the room were told to disappear or they would be dealt with.

Fitzgerald added that Michael was the most efficient officer in the whole building. He alone it seems, had the good sense to compile a list of the names and addresses of the Volunteers under siege in the GPO in case it would be difficult later on to identify casualties.

• He led the evacuation from the GPO to Moore Street.

• Was held in the area with other prisoners outside the Rotunda Hospital where he witnessed Thomas Clarke and Sean Mac Diarmiada being beaten and abused by Dist. Inspector Lee Wilson R.I.C.. He never forgot this and when the War of Independence came into play, he had the Squad shoot him dead at Gorey in Co. Wexford.

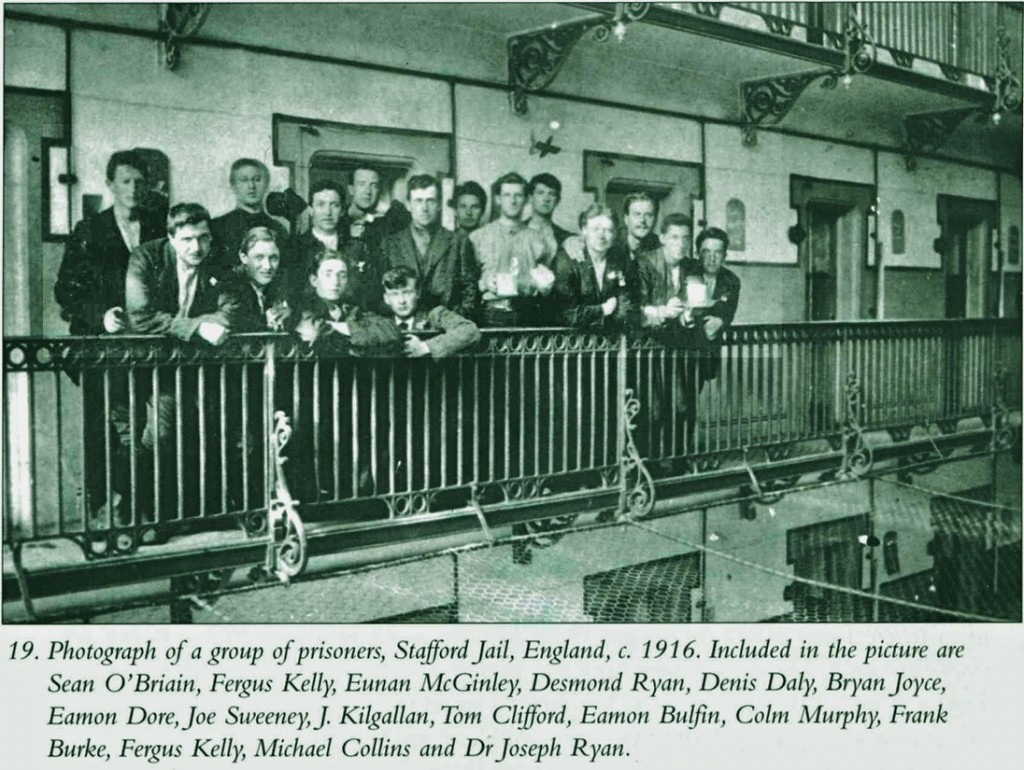

• Jail in Stafford England, then Frongoch in Wales. Then back to Ireland with a plan for Freedom.