The Ambush

The Ambush at Béal na mBláth

From “Michael Collins his life and Times” by Edward O’Mahony

History records that Michael Collins died at Bealnablath. Modern writers have decided that the proper name is Beal-na-mBlath meaning the “mouth of the Flowers”. However, authorities like Bruno O’Donoghue in his published Place Names of West Cork state that the correct name is Beal-na-Blaithe that means a “hollow between hills”, or a ravine, and this is an apt description of the place. The modern road signpost reads Beal-na-mBlath. The actual spot where Collins died is in the townland of Glanarouge and is a distance of one mile from the tiny village of Beal-na-mBlath. The Collins monument stands on the right-hand side of the road from Newcestown to Beal-na-mBlath. It was erected in 1924 on two roods of land purchased by the Irish National Army. Why it was erected on that particular position is a mystery since it does not mark the spot or even the side of the road where he died. Perhaps the engineers siting the monument decided that it would be unwise to erect it close to the stream on the left hand side and choose a site that allowed adequate space for military honours to be rendered to the First Commander-in-Chief.

The author’s memory of the place in the early 1930′s is of a narrow twisted road with a continuous strip of grass in the centre and a mud bank on the left-hand side close to the stream (the little river Noneen). There was very little tree or scrub growth. Since then, the Cork County Council have widened and surfaced the road. In the process they have removed the mud bank in places but more importantly the curve in the road for a length of over 200 yards has been removed. It is important to remember that the road and road fence were differently aligned in 1922 when the Collins convoy passed that way.

Who shot Michael Collins has been a matter of controversy since his death. The initial information was based on a statement made by Lt. Smith – the motorcyclist with the Collins convoy – to newspaper reporters in the week subsequent to the ambush. Emmet Dalton- wrote a much fuller report in the Freeman’s Journal newspaper a year after the event. It is thought that Dalton also wrote a report for the Government and that this is the report that forms the basis of the final chapter in Piaras Beaslai’s book – Michael Collins and the Making of a New Ireland. Dalton is quoted extensively in that chapter. In 1978, Dalton contributed to a film of his life and times made by Cathal O’Shannon for R.T.E. He gave a long interview on the site at Beal-na-mBlath, pointing out the position of the vehicles in the convoy and where the varying combatants were at different times during the ambush. He remarked how the site had changed in the intervening years and showed where Collins “moved from there up around the bend out of my vision.” before he was shot. Two other accounts, by private Michael Corry, co-driver of the Leyland touring-car conveying Collins and Dalton, and by Sean O’Connell who acted as a guide, represent with those already mentioned the total information from convoy personnel.

There are three official accounts from the I.R.A. side. The first is the report by Liam Deasy O/C First Southern Division to his commanding officer, Liam Lynch, on the day after the engagement, in which he stated that Collins was shot in a rearguard action in which four men participated. The second account is that which Deasy gave in his book, Brother against Brother published in 1975. Thirdly, there is the 1964 account by six then surviving Republican officers compiled by Florence O’Donoghue is in the National Library and has recently become available. In addition, the author, a native of the area, spoke with three of the twelve men whom Deasy described as walking towards Newcestown before the ambush took place. All are now dead. They spoke in confidence and were loath to name other participants but each named one person. Ten were 1st Brigade and one a 3rd Brigade man from near the locality. The twelfth man was unarmed and had acted as a judged in the Republican courts. He had heard during the day that there was something on at Beal-na-mBlath and walked over there after the day’s work. The twelve men who had been walking homewards heard the noise of the approaching convoy and ran back to the bohereen (by-road) fence and fired at the Leyland touring-car from the back of the road fence.

Bill Powell, who was walking with John Lordan on the road towards Beal-na-mBlath cross, told the writer how both of them jumped the fence of their right hand side and began to climb the steep rough hill seeking to get into a firing position. Republicans who participated in the engagement told the author that they took an oath of secrecy at the time not to reveal who was there or what happened. There were good reasons for their silence – the fear of retaliatory action by Government forces. When later, the Government imprisoned some of the participants; they gave false names and address. Life was cheap in those confused days. The death of Captain O’Brien and others near Macroom roused the anger of the Irish Free State army personnel and increased the danger of retaliation. Dreadful deeds were committed of which one of the worst was at Ballyseedy in nearby Co. Kerry where nine prisoners were tied with a rope around a mine which was then exploded, blowing the prisoners, with the exception of one who survived, to pieces.

A number of I.R.A. officers and men retreating from the fighting in Limerick and Buttevant had arrived at Beal-na-mBlath on the evening before the ambush and had made Bill Murray’s farm house Brigade Head Quarters. The sentry on duty at Beal-na-mBlath cross was a local man, by name, Denis Long. He identified Michael Collins in the military convoy that passed through on the morning of 22nd August and informed the senior officers at Murray’s. They in turn informed their commanding officer, Liam Deasy, when, he and de Valera, arrived at Murrays a short while afterwards. The O’Donoghue document shows that the Divisional officers decided in conformity with the general policy of attacking Free State convoy’s to lay an ambush on the assumption that the convoy would probably return later in the day by the same route.

When Stephen Griffin, the driver of a four-wheel dray from Bandon Brewery called to collect empty bottles from Long’s pub, his vehicle was commandeered. Griffith was ordered to drive to the selected ambush site. The horse was untackled there, a wheel was taken off and it and the unloaded crates of bottles formed into a barricade blocking the main Newcestown – Crooks town road. Griffith was sent with the horse to the Foley farmhouse at Maulnadruck and instructed to wait. A farm butt (cart) was also commandeered and used to block the bohereen on the eastern side of the ambush site.

A mine –a metal case containing sticks of gelignite – was collected by Tom Foley, Maulnadruck from John Lordan’s house near Newcestown and buried in the road on the Bandon approach to the barricade. The command wire for detonating the mine led to a plunger which was under the control of First Battalion engineer, John O’Callaghan, positioned near the entrance to the bohereen on the eastern side of the ambush site. Dan Holland O/C First Battalion was posted with him.

The ambush was laid about noon according to the O’Donoghue account. The ambush party numbered between 20 and 25 men although Lt. Smith, the motorcycle scout leading the convoy, estimated that there were “200 attackers” in his newspaper interview but his figure is not suggested by any other source. Men in the ambush left their positions from time-to-time throughout the afternoon for a quick snack in neighbouring farmhouses. The majority returned to their positions. However, a group of about ten men are reported to have pulled southwards out of the ambush party that afternoon and not to have returned but this report cannot be corroborated. It was a dry August day until a mist fell as evening approached. Liam Deasy and his adjutant Tom Crofts having returned to Divisional H.Q. in Gurranereagh shortly after the departure of de Valera from Beal-na-mBlath remained at H.Q. for the rest of the day. In the evening they both left H.Q. and walked the four miles to Beal-na-mBlath arrived there about 7 pm and then walked to the ambush site. There they met Tom Hales who was in charge and after a discussion decided that the convoy would not return that evening. A decision was made, probably by Liam Deasy, calling off the ambush and to evacuate the position.

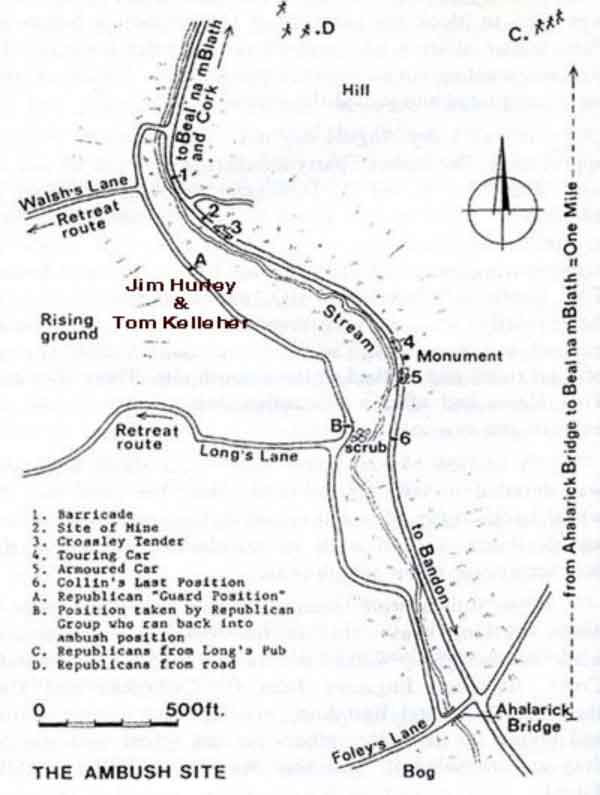

Tom Hales issued orders to take up the mine and remove the barricade. A section from Cork No. 3 Brigade under the command of Jim Hurley and consisting of Tom Kelleher and a few other men was ordered to cover the withdrawal from a position on the bohereen on the western side of the road. Tom Hales also ordered that the horse and driver be sent for and the road site tidied up. Gelignite is an extremely dangerous substance even when under the control of experts and lifting a mine a hazardous operation and it was standard Brigade practice that only those necessarily involved should be within 150 yards of the operation. Accordingly the main party left the site, about a dozen men walking south the road in the Newcestown direction while others took the road north to Beal-na-mBlath village. The 3rd Brigade section took up covering positions on the ‘bohereen’. Dan Holland and John O’Callaghan proceeded to disconnect and uncover the mine and remove the sticks of gelignite. The covering section with the exception of Jim Hurley and Dan Holland came down to the main road, began to reload the crates of bottles and tidy up the site. A few stragglers who had delayed assisted them, to go as one group to Beal-na-mBlath. It was a cloudy misty evening and about 7.30pm.

Daylight-saving time began in Ireland on 8th April 1917 and while used in railway timetables, public clocks etc. was not generally adopted by the public. Light and climate conditions determine visibility and visibility is of major importance in what happened at Beal-na-mBlath. Three accounts – those of Dalton, Deasy and O’Donoghue – fix the commencement of the ambush at between 7.15 and 7.30pm (equivalent to 8.15 and 8.30 official time) while Private Michael Corry the driver of Collins’ car shows the convoy leaving Bandon at 8.00 pm (official time). Local people fixed the time at which firing commenced as “dusk on a misty evening about half past seven”. Sunset on 22nd August was 7.37 was lighting up time 8.07 local time and the ambush almost coincided with the twilight period. The convoy left Lee’s Hotel (now the Munster Arms), Bandon about 7 pm (local time) in a happy mood, the men in the escort group standing up in the back of the Crossley tender and singing as they came northwards down the hill from Newcestown. Lt. Smith, the motor-cycle scout, was ahead, next came the Crossley tender travelling at about twenty miles per hour, then the Leyland touring-car carrying Collins, Dalton and a relief driver and, ambling some distance behind, the more-slowly-moving armoured-car, with Captain Dolan, a member of the famous “Squad”, sitting outside on the back.

Beaslai, quoting Dalton, writes: – “It was now about a quarter past seven and the light was failing. We had just reached a part of the road which was commanded by hills on both sides… when a heavy fusillade of machine-gun and rifle fire swept the road in front of us and behind us shattering the windscreen of our car”. Private Michael Corry the driver describes: “Two men of the convoy observed the time of departure from Bandon town as being 8 pm. After doing some five miles we came around a sharp curve and were then on a straight stretch of road. A single shot rang out from across the hill on our extreme left, some 440 yards away (approximately)! The Beal-na-mBlath ambush had begun!

Beaslai, quoting Dalton, writes: – “It was now about a quarter past seven and the light was failing. We had just reached a part of the road which was commanded by hills on both sides… when a heavy fusillade of machine-gun and rifle fire swept the road in front of us and behind us shattering the windscreen of our car”. Private Michael Corry the driver describes: “Two men of the convoy observed the time of departure from Bandon town as being 8 pm. After doing some five miles we came around a sharp curve and were then on a straight stretch of road. A single shot rang out from across the hill on our extreme left, some 440 yards away (approximately)! The Beal-na-mBlath ambush had begun!

The sharp curve to which Corry refers has been removed. The shot that Corry refers to was that fired at Lt. Smith the motor – cycle scout by Jim Hurley from Republican position A. Tom Kelleher fired at the following Crossley tender. The reason they gave for firing was that they realised that the main party, who earlier had left after the ambush had been called off, were walking towards Beal-na-mBlath village and would be caught by the convoy in the narrow ravine and in a very dangerous position. They had to be alerted to the danger. Some seconds after the Hurley/Kelleher shots the Leyland touring passed by Republican Position B and the men behind the fence fired at it, smashing the windscreen of the car and stopping the brass clock in the windscreen at 7.32pm. For the duration of the entire action that lasted between 20 and 30 minutes four groups of Republicans became involved and the actions of each group will be examined.

Republican Position A

Only Jim Hurley and Tom Kelleher of the 3rd Brigade section remained in position on the bohereen. The others had walked down the bohereen to the road and were helping to clear the road when Jim Hurley and Tom Kelleher heard the noise of the approaching motorcycle and Crossley tender coming from the south. The men clearing the road heard the noise also and ran for the entrance to the bohereen bringing the plunger, the coil and the gelignite but leaving the mine-case in situ (where it was to remain for about forty years when it was removed by County Council workmen in road-widening operations). The motorcycle scout dismounted after the Hurley/Kelleher shots and sought cover along the fence on the western side of the road. The Crossley tender stopped, the soldiers dismounted and loosed machine-gun and rifle fire at the Republicans. The covering section hurriedly took up poor firing positions along the fence of the bohereen. They numbered about ten and were armed with rifles and revolvers. They were out-numbered and out-gunned by the soldiers who had dismounted from the Crossley tender and were armed with two machine guns and rifles.

Lt. Smith remounted his machine, drove past the roadblock, turned left up the bohereen and saw that it was blocked by a farm butt (cart). The retreating Republicans fired on him; he turned his machine and drove back to the main group under Commandant O’Connell. No serious attempt was made by O’Connell’s men to cross the stream or to outflank the ambushers. Having accomplished their purpose of warning the others, the Republicans at position A withdrew westward by the lane leading to the Walsh farmhouse. The actual duration of the fighting at this position is not clear but, in Dalton’s account, the firing at Commandant O’Connells men lasted “only a few minutes”. The firing by the soldiers however, was very intense and, while retreating, Battalion Engineer John O’Callaghan and Jerh Mahony of Cork No.1 Brigade each received a bullet in the backside.

Republican Position B

Liam Deasy describes a group of about twelve men leaving the ambush site and taking the road northwards in the Newcestown direction. The group walked a few hundred yards northwards then left the road, crossed the stream and a small field on their right (west) side and climbed the fence of the bohereen (near its northern end). Some of them were about twelve yards into Long’s field when the last man climbing over the fence heard the motorcycle and saw the Crossley tender in the distance. He raised the alarm. They ran back, reloaded their rifles and took cover behind the bohereen fence on both sides of a dry-stone gap (the fence at this point was closed with large stones which could be rolled away and rebuilt when necessary). The motorcyclist drove by; the Crossley tender followed. The men held their fire waiting for an intimation of what to do from the 3rd Brigade covering section on the bohereen. A shot rang out from that position. Seconds afterwards the Leyland touring car drove past. The Republicans at position B fired on it from a distance of about 35 yards, smashing the windscreen.

Dalton said that he shouted to the driver “Drive like hell!” But the Commander-in-Chief, placing his hand on the man’s shoulders, said, “Stop! Jump out and we’ll fight them,” Dalton continues: ” we leaped from the car and took what cover we could behind the little mud bank on the left-hand side of the road”

Shortly afterwards the armoured car drove into the position, halting behind the Leyland touring car. Captain Dolan (a member of the “Squad”) jumped off and also took cover behind the mud bank that was about two feet high. Collins and his four comrades were then in the comparative safety of the bank. The Republicans were in a higher position on their left side and firing from behind the bohereen fence. Initially, the eleven Republicans exchanged ineffective rifle fire with the five-man Collins group but when the armoured-car with its mounted Vickers machine-gun in its dominating revolving turret began to fire at a range of less than forty yards on the men at Republican position B, they were forced to keep their heads below the top of the fence and it became almost impossible for the Republicans to fire an aimed shot. The unarmed civilian on the extreme left position described the noise as like that “from a mowing machine cutting hay” while an active participant recollected that “sloes (the berries of the black-thorn) began to fall on our faces like snow flakes in winter”.

The Republicans had, each only about ten bullets and after the initial volley got off only a few aimed shots, mainly at the armoured-car. A participant described how he “kept pasting away at the back of the armoured-car which was on his left”. The machine-gunner fired two loaded belts, each of 200 bullets and was into a freshly loaded third belt when the gun “jammed” and ceased firing. Its crew stayed within the armoured-car during the engagement.

Dalton’ s account continues “we continued this fire fight for about 20 minutes without suffering any casualties, when a lull in the enemy’s fire became noticeable. General Collins now jumped up to his feet and walked over behind the armoured-car”. Republicans said that the intense fire from the machine-gun forced them down behind the fence but when the machine-gun fire ceased they began to creep from the bohereen fence to the shelter of an adjacent East/West fence and got away along the lane. It is probable that most of the Republicans left at that time as otherwise Collins, when he stood up, walked behind the armoured-car and later ran south the road would have been an easy target for a Republican rifle-man near the stone-gap. Dalton gives different accounts of what happened next. The account quoted by Beaslai reads: “He (Collins) remained there [behind the armoured-car] firing occasional shots and using the car as cover. Suddenly I heard him shout- ‘Come on boys! There they are running up the road! I immediately opened fire upon two figures that came in view on the opposite road. When next I turned round, the Commander-in-Chief had left the car position and had run almost fifteen yards back up the road. Here he dropped into the prone firing position and opened up on our retreating enemies.” Beaslai, quoting Dalton, wrote: “Dalton, Dolan and O’Connell took up positions on the road further down. Presently the firing of Collins ceased and Dalton fancied he heard a faint cry of ‘Emmet’! He described how he and Sean O’Connell “rushed to the spot and found their beloved Chief motionless in a firing position firmly grasping his rifle”.

Dalton’s 1978 R.T.E. interview on site at Beal-na-mBlath describes how “after ten minutes of the engagement he (Collins) got up and moved to the back of the armoured-car and then moved from there up around the bend and out of my vision. But he was firing from there and I was firing from here.” The interviewer asked Dalton, “At what stage, then did you learn that he had been killed?” and the reply was: “Well, I heard – I thought I heard – the voice calling me, and I jumped up, and at that stage O’Connell had come up the road to me. He said – ‘Where is the Big Fellow?’ So I said – ‘ He’s around the corner, round the bend and we both went up there and he had been shot’ (The bank was then a continuous curve of about 250 yards). Dalton’s account continues: “The enemy must have seen that something had occurred to cause a sudden cessation of our fire because they intensified their own”. Commandant O’Connell knelt besides their dying chief, O’Connell said an Act of Contrition while Dalton kept up bursts of rapid fire. O’Connell dragged the dying man across the road and behind the armoured-car. The wound was bandaged. Then with the aid of Lt. Smith who had come up on his motorbike they lifted Collins on to the armoured-car. While doing so Smith received a shot in the neck. The convoy moved on towards Beal-na-mBlath, stopping after a few hundred yards and transferred the dying man to the back seat of the Leyland touring car with Collins’ head resting on Dalton’s shoulder. The convoy moved off, drove past the turn for Macroom and took the road to Crookstown.

Republican Position C

Republicans, walking northwards along the road towards Beal-na-mBlath on hearing the shots jumped the fence on the east side. The group included John Lordan of the 3rd Brigade and Bill Powell of the 1st Brigade who were walking together. Powell told the writer that after leaving the road they began to climb the hill seeking a position that would overlook the firing. Their progress was slow as the hill was rough and very steep and they had to cross fences. They could hear the heavy firing and the bark of the machine guns. Initially the only help they could give their comrades was to fire some shots in the air and give the impression that a military group was on the east side of the road. At a later stage when some of them got closer they fired shots into the area where the Crossley tender had stopped. Fire was returned. The only effect of this group was that they probably influenced the soldiers from the Crossley tender not to move from the cover of the road-fence. After the firing ceased and darkness had closed in Lordan and Powell moved down towards the road where they overlooked the stopped convoy but in the darkness could not see what took place.

Darkness closed in. The men from Republican positions C and D came down to the road and walked northwards towards Beal-na-mBlath village for an evening meal.

The men from Republican position A with the exception of John O’Callaghan did likewise. The majority attended the Brigade meeting at Murray’s later on. The men from Republican position D who were not scheduled to attend the Brigade meeting had their meal in the houses along Long’s lane. Three of them together with John O’Callaghan, the Battalion Engineer responsible for taking up the mine and who probably came up the interconnecting lane that joins the Walsh and Long farmyards, sat down for an evening meal in the kitchen at the Taylor farmhouse. During the meal O’Callaghan suddenly stood up and exclaimed “Christ! My arse is on fire”. When retreating with his equipment from the site of the mine he had received a bullet in his posterior but in the excitement of battle had not felt the wound.

Republican Position D

Republicans who reached this position towards the end of the action included. L Deasy, T. Crofts, T. Hales and P. Kearney. They had walked from the ambush site after the Ambush had been called off to Long’s pub in Beal-na-mBlath village. Deasy wrote: “We were in the pub about ten minutes when we heard the sound of machine-gun and rifle fire coming from the direction of the ambush position. We rushed out to a higher road, which ran parallel to the lower road. We crossed a few fields… it had not taken us more than fifteen minutes since hearing the first shots. From where we were, some three hundred yards from the actual position, we could see very little – just a lorry and the turret of the armoured car with a few soldiers darting from one position to another. We had fired a few shots when suddenly the whole convoy moved off”. The convoy with the injured Lt. Smith as a passenger in the Crossley tender drove past the sharp turn for Macroom. As it approached Crookstown village, the soldiers stopped a local man, Ted Murphy, a former member of the London Metropolitan Police who told that he was ordered to lead them to the nearest priest and doctor. Murphy went on board the tender and guided the convoy two miles further east to the nearest church at Cloughduve and to its curate, Fr. Timothy Murphy. On the way to Cloughduve a soldier said in a low voice “This is a night that will be remembered”. Ted Murphy asked why and got the answer “the night Michael Collins was killed”.

The convoy stopped at Cloughduve Church, in Kilmurry parish. Ted Murphy, accompanied by a soldier from the Crossley tender, walked to the presbytery close by and knocked at the door. Fr. Timothy Murphy subsequently told the events of that night to the historian, Fr. A Gaughan: “Between 11.00 and 11.15pm (presumably modern time) there was a knock on the door of my house. My housekeeper answered it. She called me and said I was wanted outside. A soldier and a civilian who lived locally were standing at the doorway. The soldier asked me to come outside, as there was a soldier shot. It was a dark night and the soldier carried in his hand an old carbide lamp, which was giving a very bad light. I walked out to the roadside where the convoy had stopped. There was a soldier lying flat with his head resting on the lap of a young officer. The young officer was sobbing and crying and did not speak. There was blood on the side of the man’s face. I said an Act of Contrition and other prayers and made a sign of the Cross. I told an officer to wait until I got the Holy Oils. I went to the house and when I returned the convoy had gone”. Dalton also described how the priest turned his back and walked away and, as he did so, O’Connell pointed the gun at his back, released the clip and was about to fire. He wrote that he snapped at it (the gun) and tilted it skywards. “The shot actually discharged. Had I not jerked it the priest would have been shot”.

Ted Murphy told Donal O’Mahony in the late fifties that earlier in the day he had been in Cork city. Later that evening, after he had come home to Crookstown, he heard very heavy firing form the direction of Beal-na-mBlath. After the firing ceased, he began to walk from his home east of Crookstown Village, towards Beal-na-mBlath.

He was a short distance west of Crookstown, at Bellmount, when the Crossley tender stopped. He was ordered to board and guide them to the nearest priest and doctor. Ted Murphy accompanied the soldier to the door of the priest’s house and he was the local civilian that the priest recognised. Ted Murphy said nothing about an officer pointing a gun at the priest but remembered that an officer went across the road from the Church and began to question and threaten a group of young men standing talking beside the wall. He questioned the men about their Republican views and not getting a satisfactory quick answer fired a shot between the legs of one man. Murphy claimed that he succeeded in persuading the army officer that the men were not Republicans. Murphy heard an army officer say that the priest was not coming back and ordered the lorry to drive away. The priest in a sermon in Kilmurry Church, on the following Sunday regretted that all he “could do for that good man, Michael Collins, was to give him conditional absolution”.

The officer and Ted Murphy heard the order to drive off. They boarded the Crossley tender and Murphy guided them as far as the pub in Aherla village where he was allowed to leave the vehicle. A local man, 24 year-old medical student, Dan Walsh, was picked up there and ordered to guide them to Cork. He remained with the group until they arrived at Ballincollig when he was allowed leave to walk home to Aherla. Dalton described the journey to Cork as a nightmare ride and O’Connell said “we went astray many a by-road” The convoy tried to get to Cork via Ovens Bridge on the main Cork-Macroom road south of the River Lee but the bridge had been blown up by the Republicans earlier that month. The convoy got lost in the maze of roads around Kilumney. They travelled through fields using their army-coats to give traction to the vehicles. The Leyland touring car and the armoured-car bogged down and were abandoned. Collins’ body was taken on the men’s shoulders and put on board the Crossley tender. Eventually the Crossley tender with a shocked, demoralised group on board arrived via the old Cork-Aherla road into Ballincollig and then to Cork city. The body of the dead Commander-in-Chief was brought to the British Military Hospital at Shanakiel, where it was seen by a number of doctors including Dr. L. Ahern who from his army experience concluded that the large wound was probably caused by a dum-dum bullet. An autopsy may have been held but there is no record of it available. No post-mortem was carried out on the body at Shanakiel Hospital.

It was essential to notify the Government as soon as possible of Collins’ death. There was no telephone connection working between Cork and Dublin and the notification of his death was sent to Valentia Radio station, relayed from there to New York, then to London and finally to Dublin. The news shocked his Provisional Government colleagues in Dublin; military barracks were notified and everyone was in deep gloom. General Mulcahy composed his famous message to the Army and country: “Stand calmly by your posts. Bend bravely and undaunted to your work. Let no cruel act of reprisal blemish your bright honour. Every dark hour that Michael Collins met since 1916 seemed but to steel that bright strength of his and temper his gay bravery. You are left, each inheritors of that strength, and of that bravery. To each of your falls his unfinished work. No darkness in the hour; no loss of comrades will daunt you at it. Ireland! The Army serves – strengthened by its sorrow”.

General Tom Barry, a prisoner in Kilmainham Jail since the capture of the Four Courts, recalled what happened when the prisoners heard the news of Collins’ death in West Cork. “There was a heavy silence throughout the jail and ten minutes later from the corridor outside the top-tier of cells, I looked down at the extraordinary spectacle of about a thousand kneeling Republican prisoners spontaneously reciting the Rosary aloud for the repose of the soul of the dead Michael Collins…………. I have yet to hear of a better tribute to the part played by any man in the struggle with the English for Irish Independence”. For Tom Barry, it was a very special day. He had been married on 22nd August a year earlier, and among the wedding guests were Michael Collins, de Valera, Liam Deasy, Harry Boland, Dick Mulcahy and Emmet Dalton. A year later Collins and Boland were dead and the guests were waging war on each other. Liam Deasy would write in 1974, “when I first met him, fifty-six years ago, I considered him then to be the greatest leader of our generation and I have not since changed that opinion.” Jackie O’Brien, Mallow – a dispatch rider with the First Southern Division – recalled being with de Valera on 23rd August at Glashabee, Beeing (North Cork) when they heard of Michael Collins’ death. On hearing the news de Valera said with great emotion: “My God, it is too bad; there is no hope for it now”.

The message from General Mulcahy had a steadying effect on the Army and, with the exception of three young Republicans shot in cold blood at the Red Cow Inn in Clondalkin, the Army obeyed General Mulcahy’s order. Emmet Dalton prevented some Cork-based officers and men from setting out on a revenge mission. Army lorries from Bandon and Macroom patrolled the Beal-na-mBlath area, but carried out no act of revenge. A few days later, Republican Divisional Headquarters having shifted further west towards Coppeen, an army search party surrounded the Wood’s home in Muinegave. Richard Woods said to the officer in charge: – “Why didn’t ye come a few days earlier and ye would have got them all – was it that ye were afraid of them?” The house was thoroughly searched and some beds were ripped open, but otherwise no harm was done and the search yielded nothing.

Collins’ body was brought by boat to Dublin and then removed to St. Vincent’s Hospital for embalming by Oliver St. John Gogarty. It was later brought to the City Hall where it lay in state. The state funeral to Glasnevin was an impressive event. With a strange touch of irony, the body of the dead Commander-in-Chief was carried on the gun carriage that had been used for the attack on the Four Courts. The huge attendance that lined the streets, or was part of the three-mile funeral procession, was visibly affected with grief. His I.R.B. friend, General Mulcahy, delivered the funeral oration at the graveside. Tributes flowed in from abroad. English newspapers had banner headlines. The Daily Telegraph wrote: “The dead man was of the stuff of which great men are made”.

To return to the immediate aftermath of the ambush, after the convoy had left the scene of the ambush Stephen Griffin, having collected the dray, drove home in the darkness to Bandon. The postponed Brigade meeting convened at Murray’s at 9.30 pm. Those in attendance included, Tom Crofts Divisional Adjutant; Con Lucey, Divisional Director of Medical Services; Sean Culhane, Divisional I/O; Tom Hales, Brigade Commandant; Jim Hurley, Brigade Commandant; Tadhg O’Sullivan, Brigade Commandant; John Lordan, Brigade Commandant; Pete Kearney, O/C Third Battalion; Tom Kelleher, O/C Fifth Battalion; Sean Hyde, O/C Western Command; Dan Holland O/C First Battalion; Mick Crowley, Brigade Engineer.

Participating officers who stated that as far as they knew there was no casualty on either side made a report on the ambush.

The main purpose of the meeting was to discuss the proposal “as the towns are now occupied the struggle should be discontinued” Deasy elaborated on the views expressed at his meeting with de Valera the previous night. With the exception of one officer, all of those present were in favour of peace provided an honourable means could be found for ending the conflict. The Collins-convoy guide, Ted Murphy, was allowed to leave the convoy at Aherla and walk (through Cloughduve) home to Crookstown. He told the news of Collins death to a few people and it spread quickly through the village. At the forge in Crookstown that night getting his black pony shod was Sean Galvin, a brother of Michael of Lissarda. Sean Galvin, on hearing this information, mounted his pony, rode the two miles to Murray’s house and told the assembled staff the momentous news that he had heard. This caused an immediate emergency. Galvin was ordered to return to Crookstown, to question Ted Muprhy personally and establish the facts.

The Brigade staff fearing, if the information about Collins’ death proved true, an immediate descent by Government troops on the area and possible reprisals on families, made preparations to leave Murray’s house and the surrounding area. Galvin returned to Murray’s shortly before midnight to confirm his earlier report. The evacuation began immediately. The entire group marched out, having placed scouts ahead, behind and on the wings and took the road, guided by men of the Kilmurry Company, northwest towards Kilmurry village. They by-passed this village and, at about two in the morning, arrived at the Taylor farmhouse, in Deermount, where they laid down for the night and remained for a few days.

On the night of the ambush, Lieutenant Smith’s motorcycle was found by the roadside. It was kept by Tom Hales for many years and then given to Bruno O’Donoghue for use by him in his work as a Cow Testing Supervisor. An officer’s cap, presumably Collins’, was taken from the site the following morning and brought to Jim Murray’s house at Raheen. A local person, the now Secretary of Kilmurry Historical Society, remembers Brigade Commandant Tom Hales sitting on the settle-seat where the cap was thrown into the kitchen. Hales showed strong displeasure. The young chaps from the locality who brought the cap were ordered to take it out. They then threw it into a bunch of briars near a pool of water. It was retrieved with a hayfork the next day. Fr. Jeremiah Coakley, at the Newcestown parish station in October at Murrays, asked for the cap, so that he could give it to a sister of Michael Collins. The cap (which did not have a badge) was given to Fr. Coakley.