Austrialians Easter Rising 1916

Journal of the Australian War Memorial

Called to arms: Australian soldiers in the Easter Rising 1916

Jeff Kildea

On 24 April 1916, Easter Monday, members of the Irish Volunteers and the Irish Citizen Army, under orders from the Military Council of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, occupied buildings in strategic locations throughout the city of Dublin. At 12.30 pm their leader, Padraic Pearse, a teacher and barrister turned revolutionary, emerged from the General Post Office, which had been seized by the insurgents shortly before, and read aloud to the small but bemused crowd gathered in Sackville Street (now O’Connell Street) the proclamation of the Irish Republic. For the next six days the insurgents, armed only with rifles and shotguns and numbering less than 1000, maintained their hold on the city against the military might of the British Empire, which assembled a force of at least 16,000 with armaments that included artillery and the gunboat Helga.

Diggers in Dublin

{2} Among the Crown forces who put down the rising were Australian soldiers in Dublin at the time the fighting broke out. This little known involvement of Australian soldiers in the Easter Rising is alluded to in a biography of Michael Collins by Tim Pat Coogan who, after describing the treatment of Irish prisoners by soldiers of the British Army, wrote:

And the cheery word, and even the cup of tea, was not unknown, particularly when an Australian unit relieved the Royal Irish Rifles from Belfast.

Unfortunately, Coogan did not identify the Australian unit or disclose his source for saying there was such a unit in Dublin during the Easter Rising. Nevertheless, other published works on the rising also mention the presence of Australians in Dublin.

{3} Roger McHugh’s 50th anniversary anthology of the rising Dublin 1916 contains two eye-witness accounts that refer to “Anzacs” being at Trinity College. One is an article by “One of the Garrison”, which originally appeared in Blackwood’s Magazine in July 1916.The article describes the defence of the College, a strategic location in the heart of Dublin that the insurgents inexplicably failed to occupy at the outbreak of the rising. The writer related how “the Anzacs”, whom he said had been on the roof of the College since an early hour, shot “a despatch-rider of the enemy”:

It was wonderful shooting. He was one of three who were riding past on bicycles. Four shots were fired. Three found their mark in the head of the unfortunate victim. Another of the riders was wounded and escaped on foot. The third abandoned his bicycle and also escaped. This shooting was done by the uncertain light of the electric lamps, and at a high angle downwards from a lofty building.

The writer later met the soldiers:

After being relieved, I joined the Anzacs on the roof. They were undoubtedly men fashioned for the enjoyment of danger. And certainly it would be harder to find nicer comrades. Alas for thousands of these fine soldiers who have left their bones on Gallipoli!

And he gave them even higher praise by claiming: “There can be no doubt that the accurate fire maintained from the College was an important factor in the salvation of the City.”

Trinity College (left). Anzac marksmen on the roof fired on the insurgents.

{4} The other eye-witness account republished in Dublin 1916 is the diary of Miss Lilly Stokes, originally published in Nonplus in 1916. In her diary Miss Stokes wrote:

I went to the Provost’s House [at Trinity College], where the Mahaffeys gave me a welcome cup of tea. They had barred and shut themselves in. They told me Mr. Healy of the Irish Times said it was feared that the same state of affairs reigned in all the other towns, but of course nothing was known, the telegraph wires being cut. While at tea, Mr. Alton, the Fellow and an O.T.C. Captain, came in to ask for beer for the 30 Anzacs he had collected to help to defend the College.

However, neither witness identified the Anzacs or their units, or specified how many were from Australia and how many were from New Zealand. Furthermore, Miss Stokes had no personal knowledge of the Anzacs, relying rather on what Mr Alton had said.

Captain E. H. Alton took command of the Trinity College OTC during the rising

{5} Another contemporary reference to Anzacs is contained in the 1916 account by Wells and Marlow, which states:

Stray soldiers were summoned from the adjacent streets and from the Central Soldiers’ Club hard by the College to reinforce the garrison; these included some “Anzac” sharpshooters.

{6} More recent published accounts of the rising also refer to Anzacs at Trinity College. Max Caulfield in his 1963 work, The Easter Rebellion, included a number of references:

Trinity was put into a state of siege by the University O.T.C. within an hour of the Rebellion starting. Early in the afternoon, a handful of Canadian and Anzac soldiers, in Ireland for a brief furlough, made their way into the university when they learned it was being held for the Government. Several more were recruited by Trinity students who paraded the streets in mufti, looking for anyone who would help. …

[The military] had opened up intermittent sniping on the Sackville Street positions from three different places: the roof of Trinity College, where the Canadians and Anzacs, aided by the O.T.C. and units of the Leinster Regiment, were heavily entrenched; …

Premises on both sides of [Abbey Street] were soon blazing furiously, the fire spreading both north and south. Taking advantage of this gap which opened a ready way into Sackville Street, the military began infiltrating until they were stopped by fire from the rebels under Lieutenant Oscar Traynor … . Traynor’s men brought on themselves a double wrath—first, of the military in Lower Abbey Street and second, of the Canadian and Anzacs on the buildings at the corner of D’Olier and Westmoreland streets—by returning the fierce fire so effectively that the military advance was halted. …

But, like Coogan, Caulfield did not identify the sources for these statements.

{7} In 1967 F. X. Martin wrote an article surveying the historiography of the rising in which he described Caulfield’s The Easter Rebellion in these terms:

For an impression of Easter Week Caulfield’s book can hardly be bettered … But … Caulfield falls lamentably short of the standards required for reliable historical writing. He gives no footnotes and therefore his statements are not necessarily verifiable. Caulfield is a novelist and this quality shows in his artistic touching up of incidents. … When all has been said it must be admitted that Caulfield’s book is a tour de force, the fruit of extraordinary industry and research

{8} Applying the narrator’s skill that Martin attributes to him, Caulfield described an encounter between “an Australian sergeant” and W. J. Brennan-Whitmore, one of the Irish prisoners, which took place after the insurgents had surrendered.

Later an Australian sergeant came to the doorway and shouted obscenities at them. Then he asked, “‘Ere, what about the German sniper?”

“We had no German snipers,” insisted Brennan Whitmore indignantly. “By the way, you British had some pretty good snipers yourselves. We had a cable across Sackville Street and one of your fellows hit the canister from Trinity.”

The Aussie gave a whoop. “Do you mean I got it?”

“You mean it was you?” asked Brennan Whitmore astonished. “Well, you didn’t cut the cable, but you were within half-an-inch of doing so.”

“Listen,” said the Aussie, suddenly friendly. “I’ll try to find you something to eat.” Smiling happily he went away.

“You know, that fellow’s crazy,” said Thornton.

In a short time the Aussie returned carrying a big biscuit tin and a jug of cold tea.

“I’m sorry, but this is all I could scrounge,” he apologized. “But anyway, here, take it,” and added, “for Auld Lang Syne!”

Brennan Whitmore looked at the tin of biscuits—everyone broken—at the jug of cold tea, and at the eager, friendly face of the Australian. Then he reached out for them. “For Auld Lang Syne,” he said.”

{9} Even though Caulfield did not identify the source for this detailed narrative, the description of the episode is probably based on Brennan-Whitmore’s own account of the event, which appears in his memoir Dublin burning. This work was completed in 1961, some forty-five years after the rising, but it incorporates material Brennan-Whitmore wrote closer to the event, including an article that appeared in An tglach in 1926 which he revised and republished in 1953.

{10} Brennan-Whitmore is most likely also the source for the reference to an “Aussie marksman” in Peter de Rosa’s Rebels:

The GPO had no radio or telephone link-up even with its outposts across the street.

Captain Brennan Whitmore on the east side threw a ball of twine across the boulevard. A can was fixed on the twine to carry messages. It was on the third journey across when a volunteer Aussie marksman in Trinity scored a direct hit on it.

From then on, the rebels simply sent over pieces of paper, some of which arrived with perforations.

{11} More recently, Michael Foy and Brian Barton in The Easter Rising refer to the presence of Empire troops in Trinity College:

A motley crew of vacationing Irish, Australian and South African soldiers came under fire in O’Connell Street and took refuge in Trinity College

But once again, there are no details that identify the Australians or their unit (or units).

{12} Among the published literature, there is one account that does identify the Empire defenders of Trinity College: the 1916 Rebellion Handbook. In a section headed “Colonial Soldiers who Assisted in Defence of TCD” it names six South Africans, five New Zealanders, two Canadians and one Australian, the last identified as “1985 Pte McHugh, 9th Aus. Infantry Force”. This is the most specific of the published sources, but the list includes only six Anzacs, not the thirty to whom Miss Stokes referred, and it does not square with Brennan-Whitmore’s reference to an Australian sergeant being at Trinity College. However, a New Zealand sergeant is among the colonial defenders named in the 1916 Rebellion Handbook, so it is possible that Brennan-Whitmore mistook the New Zealander for an Australian.

{13} All in all, the published literature confirms the presence in Trinity College of a group of Anzacs, who by acting effectively as snipers participated in putting down the rising. One of the Anzacs is named and identified as an Australian, but beyond that the published literature does not provide much other information; nor does it verify Tim Pat Coogan’s reference to an Australian unit being involved in looking after Irish prisoners.

{14} The Australian War Memorial’s personal records collection includes diaries and letters of Australian soldiers who visited Ireland during the war. Two of the records are of particular relevance. One is the diary of Lieutenant John Joseph Chapman of the 9th Battalion, and the other is the diary of Driver George Edward Davis of the 2nd Australian Motor Transport Company – both of whom were in Dublin during the rising.

Private Chapman

{15} Chapman was a private in April 1916 when he visited Ireland while on convalescent leave. He had been on Gallipoli since the first day of the landing, 25 April 1915, until illness caused his evacuation in August 1915 to Malta and from there to England. On the night of Thursday, 20 April 1916, Chapman and an unnamed companion caught the train and ferry to Dublin, checking in the next morning at the Waverley Hotel in Sackville Street. They spent the Friday sightseeing in Dublin before taking a train the next morning to Killarney to visit the lakes, a popular spot for Australian soldiers on leave in Ireland. On the journey Chapman and his mate teamed up with two Australian nurses, who were members of the Red Cross Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) and who were staying in Dublin at Ross’s Hotel in Parkgate Street (now rebuilt as the Ashling Hotel).

{16} After a weekend of sightseeing, horse riding and boating on the lakes the tourists caught the train back to Dublin on Easter Monday, but they only travelled as far as Limerick before the train was stopped, no doubt due to events then unfolding in Dublin. After a delay the train was diverted to the south but it was again delayed at Cork, where Chapman and his fellow travellers were forced to stay aboard the train overnight. The train left Cork the next afternoon at 2.30 but the journey to Dublin, usually three hours, took twice as long. When they arrived at Kingsbridge station (now Heuston station) Chapman was escorted to the nearby Royal Barracks (now known as Collins Barracks) and told to be ready for duty at any time.

{17} The next morning, Wednesday 26 April, Chapman found himself in the thick of the fighting. When the rising began the Royal Barracks had been home to the 10th Battalion of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers – 37 officers and 430 men. The insurgents had seized buildings on both sides of the Liffey in the vicinity of the barracks and a group of about twenty men under Sean Heuston occupied the Mendicity Institution on the south side, thus preventing troops moving along the northern quays toward another insurgent stronghold at the Four Courts. The British decided to capture Heuston’s position in order to free up their access along the quays. Foy and Barton describe the attack in The Easter Rising:

By now Heuston estimated that he was surrounded by 300 to 400 troops. The British attack began with rifle and machine-gun fire and as combat developed the shooting was frequently at close quarters, sometimes as close as 20 feet. At about noon the British tried a new tactic by sending soldiers creeping along the quay until they reached a wall in front of the Mendicity, from behind which they hurled hand grenades into the building. … Gradually, as one of the defenders later wrote, “The small garrison had reached the end of its endurance. We were weary, without food and short of ammunition. We were hopelessly outnumbered and trapped.” As he faced the certainty of being shortly overrun Heuston consulted his men and decided that the condition of the wounded and the safety of his entire garrison necessitated surrender. Although a number of men dissented, the order to that effect was obeyed and the Mendicity became the first rebel garrison of the Easter Rising to capitulate.

{18} Chapman’s account is much briefer:

Given rifle and ammunition and had to fight enemy in the streets. Nearly got hit several times. Only a few casualties on our side.

{19} Chapman remained on duty all that day and night, not returning to the barracks until the following morning. Thereafter, his tour of duty in Dublin consisted mostly of guard duty at the barracks or the nearby Arbour Hill military prison, which was filling up with captured insurgents. Sir Roger Casement had been held there briefly the week before on his way to London and Pdraic Pearse was imprisoned there after he had surrendered to Brigadier William Lowe on the afternoon of Saturday, 29 April. Chapman’s diary does not record whether Chapman was aware that he was guarding the leader of the rising. What it does indicate, however, is that on the first night of Pearse’s captivity Chapman was only a short distance away visiting Ross’s Hotel where he took tea with the Australian VADs exchanging stories of their experiences during the rising.

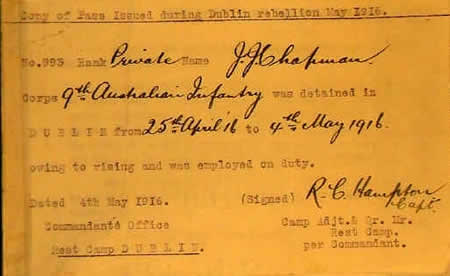

{20} On the afternoon of Tuesday, 2 May, Chapman was given leave until 9 o’clock the next morning. He took the opportunity to walk into the city centre to view the damage caused during the rising. Two days later he was on his way back to England armed with a chit signed by Captain R. C. Hampton, Adjutant and Quarter Master at the Dublin Rest Camp certifying that Private J. J. Chapman of the 9th Australian Infantry had been detained in Dublin from 25th April to 4 May 1916 “owing to rising and was employed on duty”. Following his brief but action-packed sojourn in Ireland, Chapman remained in England for another three months before crossing the Channel to France where he rejoined the 9th Battalion on 9 August.

Private Chapman’s chit explaining his absence.

Private Chapman’s chit explaining his absence.

{21} Chapman’s diary makes frustrating reading because of its brevity – much of interest is hinted at, but not spelt out in detail. This is particularly so in relation to his stay in Dublin. He wrote only a few lines about each day, with not much description of the part he played in the suppression of the rising. If Chapman’s diary is frustratingly brief, that of Driver George Edward Davis makes up for it – at least in vivid detail.

Private Davis and Private Grant

{22} Davis, like Chapman, was on leave in Ireland when the rising broke out. He, too, had served on Gallipoli – in his case, from 11 May to August, when enteric resulted in him being sent away to recuperate. Initially evacuated to Lemnos, from there he was transferred to England aboard the Aquitania in October. Davis was treated in military hospitals at Hammersmith and then Feltham, and upon discharge was posted to AIF Headquarters in Horseferry Road, London, where he became an ambulance driver.

{23} In April 1916 Davis was given leave and on the evening of Thursday, 20 April, he left London by train, crossing over to Kingstown (now Dn Laoghaire) by ferry on Good Friday morning. He was with a mate from the Australian Motor Transport Section, Private Bob Grant. Like Davis he was invalided to England after falling ill at Gallipoli in September 1915.

{24} On Easter Saturday the two men took the train to Killarney to visit the lakes. They spent the weekend seeing the sights, before catching the Sunday evening train back to Dublin. Unlike Chapman and his mate, who did not leave Killarney until the next day, Davis and Grant were in Dublin when the rising broke out. In fact, they witnessed a group of Volunteers making their way to the post office:

A squad of about forty men and boys, all carrying firearms, passed us. There were all makes of deadly weapons and all calibres from pea-rifles to shot-guns. Many of them wore a bluish-grey uniform similar to those worn by German soldiers. They were a motley crew, but the grim look on their faces told us they were not on pleasure bent, and were not then interested enough to enquire.

{25} A short while later, a sergeant in the Royal Dublin Fusiliers approached the two Australians and warned them to leave Dublin as the Sinn Feiners were about to rise and attack the city. At first Davis did not take the warning seriously. After hearing rifle fire, they joined a crowd of onlookers that had gathered on the corner opposite the old Parliament House, near Trinity College, and observed insurgents on the roof of the City Hall firing at people in the street below. People implored the Australians to hide, telling them they would be shot, but they nonchalantly replied that they were tourists and disclaimed any interest in the fight. But their complacency was soon dispelled:

walking towards Parliament Street, we were brought to our senses by a rifle bullet which struck the kerb nearby, and was followed by a quick succession of shots. I ducked into the doorway as a bullet struck the concrete pillar close to my head, the chips stinging in my face. My pal dodged around the corner, and knowing discretion to be the better part of valour, I followed.

{26} As they joined the civilians fleeing the scene, a man running alongside them was shot in the back and fell to the ground. They dragged the man around the corner and bundled him into a taxi. Davis and his companion crossed over the river to the north side, but upon sighting two insurgents with rifles they took refuge in a second-hand furniture shop where they discovered a small family of refugees whose motor car had been confiscated by the insurgents. The family lived at Rathmines, one of the better suburbs of Dublin, and offered to take Davis and Grant with them to their home. Covering their uniforms with civilian clothes, the two Australians tagged along with the locals as they walked through the streets to Rathmines, eventually arriving at a large mansion where Davis was impressed at being waited on by liveried servants. Invited to stay with the family until the rioting had ceased, they decided it would be wiser to report themselves to the military authorities, which they did after dinner.

{27} At Portobello Barracks (now known as Cathal Brugha Barracks) just off Rathmines Road, they were informed there was no transport back to England and were given a rifle and ammunition and told to protect themselves and the barracks. That night they joined a party of 70 men detailed to escort arms and ammunition to Dublin Castle. They set out on a roundabout route that brought them down near the Liffey. As they passed under a street lamp a volley of rifle shots rained down on them “from a dozen rifles across the river from the windows of the upper storeys of the Four Courts Hotel.” Davis described the scene:

Above and around us bullets “pinged” and broken glass clattered to the footpath. The horses bolted and vanished in the darkness, and the troops did likewise. I ducked for cover with the rest and dodged with several of my comrades round the pillars of a nearby building. … I at once knew where to find shelter, and bending as low as I could, I ran forward to the cover of a low stone wall skirting the river. Our men in charge had vanished, our ammunition waggons had done likewise, and apparently no one knew exactly where the barracks lay.

{28} The remaining men, thirty out of the original party of seventy, made their way to Kingsbridge station where they stayed the night, and for the next few days they were assigned to guard duty, though not very conscientiously, judging by Davis’s account of Wednesday 26 April:

I was having a nap in a railway carriage about midday, and failed to hear our guard alarm sound. Waking a few minutes afterwards, the place was a scene of activity. The station was being attacked, and jumping up, I could see plainly that the attacking party had no chance as they were hopelessly outnumbered. However, in the affray, one Tommy officer fell wounded. The end came when a small howitzer opened fire on a group of brick buildings close by, and shot several gaping holes in the walls. At dark the guards were doubled.

{29} The next day he went with a party escorting stores to various parts of the city, including Trinity College where he records that he “noticed a digger and several ‘Enzedders’ amongst the armed guard. They were evidently in a similar predicament to ourselves.” Presumably the digger was Private McHugh.

{30} Like Private Chapman, Davis and Grant on their trip to Killarney Lakes had met up with Australian nurses who were staying at Ross’s Hotel. On the Saturday the two men visited them:

Hearing that the Ross Hotel was under observation by the military, my pal and I went over to [visit] two Australian nurses, who journeyed to Killarney with us, [and] were staying there. We found them safe but a little scared as a stray bullet occasionally whistled through their window; and, after a good meal of bread and butter and tea (a contrast to bully beef), we returned to our billett [sic].

The nurses may well have been the same VADs that Chapman referred to, as they were all in Killarney on that Easter weekend and would have travelled down there on the same train.

{31} Once the fighting had ended, Davis was keen to return to England, so on Monday, 1 May, he and Grant called on Colonel Cruce to obtain a letter explaining their absence. The colonel refused, saying he would be glad to do so in a day or two, after the sniping danger was over. Despite Cruce’s opposition, Davis and Grant managed to obtain the necessary documentation enabling them to catch the Holyhead ferry that night, reporting for duty at Horseferry Road the next day.

{32} Despite efforts by his commanding officer to retain him in London, Private Davis crossed over to France at the end of July 1916 and joined the 4th Ammunition Sub Park. Bob Grant remained in England where he worked as a driver with the Red Cross and the Australian Motor Transport Section.

Private McHugh

{33} Private McHugh, the Australian soldier who assisted in the defence of Trinity College, did not leave any papers, and the 1916 Rebellion Handbook provides no further information about him or his activities at the College. But a combination of his AIF personal file and documents in the Manuscripts Department of Trinity College Library enable the events in which he was involved to be reconstructed.

Private M. J. McHugh, 9th Battalion, AIF.

Private M. J. McHugh, 9th Battalion, AIF.

{34} Michael John McHugh had sailed from Australia with the 5th Reinforcements for the 9th Battalion in April 1915. Two months later he joined the battalion on Gallipoli, and remained until he was admitted to hospital with influenza and enteric fever and evacuated to Malta on board the hospital ship Somali. After a month at the Imtarfa Military Hospital, he was transferred to England and admitted to the 1st Southern General Hospital, Edgbaston. At the end of November he was discharged to duty but did not return to the 9th Battalion until July 1916. In the meantime, during Easter week, he spent an eventful few days in Dublin.

{35} When news of the rising reached the College, the Chief Steward Joseph Marshall directed Porters Halpin and Wilson, whom he armed “with Fenian Pikes, which I had seized whilst in the DMP in 1867”, to lock the front gate and to invite into the College all passing soldiers. Those invited in included McHugh who is recorded as having served there from 24 April to 5 May. James Glen in an account of the rising wrote that while walking down O’Connell Street he and a colleague were fired upon. He continued:

We realized that we were probably the target and ran down to O’Connell Bridge, where we were joined by about half a dozen soldiers (Australians and I think one or two South Africans) who were on leave and had been attracted by the firing.

My friend and I … took the party into College. … The Australians and South Africans volunteered to man the roof overlooking College Green where there were the best opportunities for experienced riflemen.

{36} Glen’s account is dated 1 December 1967, more than fifty years after the events he describes, which may account for his reference to Australians in the plural when other evidence suggests that McHugh was the only Australian in the College. Nevertheless, it is not possible to be categorical, as there are other documents in the Trinity archive that suggest that not all of the defenders received recognition for their part in the defence of the College. And another eye-witness account (albeit also written well after the event) raises the possibility that there might have been more than one Australian at the College. Arthur Aston Luce, a lieutenant in the 12th Royal Irish Rifles, was on leave in Dublin at the outbreak of the rising and in 1965 he wrote:

There were soldiers on leave or holiday, like myself; there were several soldiers who came into College to take refuge from the firing in the streets. I remember one or two Australians among them.

{37} Luce does not provide any more information on the Australians and does not specifically refer to McHugh, but he does identify the pseudonymous author of the Blackwood‘s article “Inside Trinity College” as John Joly, FRS, Professor of Geology. As set out above, Joly’s article described the shooting of a despatch rider, an event that in all probability involved McHugh. James Glen also described that incident:

[O]ne of the marksmen on the College roof shot and killed a motor dispatch rider in SF [Sinn Fin] uniform in the street outside the Provost’s house, his body being brought into College through the Front Gate.

{38} The dead insurgent is identified in the 1916 Rebellion Handbook as Gerald Keogh aged 20 years. The shooting is also mentioned in a handwritten letter dated 10 May 1916 from Gerard Fitzgibbon to William Hugh Blake:

We had five Anzacs, two, or perhaps three, Canadians … three South Africans, one in a Kilt … almost all men on leave or sick furlough in Dublin, who had been fired upon when – unarmed – as they were walking through the streets. … One thing that terrified was early on Tuesday morning, just after Dawn. Three of their dispatch riders came pelting down on bicycles from Stephen’s Green, bringing dispatches to the Post Office, and we had twelve or fifteen men posted in windows and on the roof in front of College. They fired on the cyclists. Killed one, wounded another, and the third left his bicycle & rifle & bolted down a side street. No doubt he went back to his headquarters and told them the College was stuffed with armed men. The booty collected was three bicycles, five rifles, 400 rounds of ammunition, & their dispatches, and of course the corp [sic – corpse]. We planted him out later on to fertilise the Provost’s daffodils. … One Anzac got nine, but he was a marksman, and the Anzacs were given all the eligible situations, which it must be allowed they deserved. They were an extraordinary gang. I have never seen their like. The man they shot on the bicycle in the early dawn was riding fast, it was a hard shot at a downward angle from a high window, I believe they only fired four or five shots and he had two through his head, one through his right lung, and a fourth that hit and winged the second man of the party. If they hadn’t concentrated so much they would have bagged all three.

{39} The despatch rider’s body was brought into the College by Acting Porter George Crawford, who the next day wrote in a report:

At 4.15 A.M. on the 25th I was ordered by Lieut Luce to arouse the Provosts House, so that a Sinn Feiner, who was shot at the foot of Grafton Street, could be brought in that way, three more men and myself succeeded in bringing in the dead body, also two bicycles, two Rifles, 1 Revolver, 1 Bandolier & Kit.

{40} Elsie Mahaffy, the daughter of the Provost of Trinity College described in her diary kept during Easter Week how the dead insurgent was brought into the Provost’s house. She wrote that he had been carrying a rifle, a revolver and plenty of ammunition and money, and added:

For 3 days he lay in College, in an empty room. When necessary he was buried in the Park and later when quiet was restored was disinterred and sent to the morgue, but during the fortnight while he lay in College; though well dressed and from a respectable street, no one ever came to ask for his body.

His friends must have seen him fall but apparently were too cowardly or too callous to come & secure him decent burial.

{41} It is interesting to note that in his letter, Fitzgibbon claimed “One Anzac got nine” in a way that suggests he meant that the Anzac had killed nine insurgents. But that does not square with the information available on casualties suffered by the insurgents, which suggests that Gerald Keogh was the only one killed in the sniping war conducted in the College Green area. Nevertheless, he was not the only contemporary to claim that the death toll was higher than has been acknowledged. In Sinn Fin and the Irish Rebellion, a polemical pamphlet published in Melbourne in 1916, D. P. Russell quoted from a letter said to have been written by a New Zealander, Corporal John Godwin Garland, to his father:

On Saturday morning we killed a woman who was sniping from an hotel window in Dame Street. When the RAMC brought her in we saw she was only a girl about 20, stylishly dressed, and not at all bad-looking. She was armed with an automatic revolver and a Winchester repeater. Altogether we Anzacs were responsible for 27 rebels (twenty-four men and three women).

{42} Russell’s pamphlet provides no further information about Garland or the provenance of the letter. However, one of the colonial defenders of Trinity College identified by the 1916 Rebellion Handbook was “3/1315 Corporal Garland, New Zealand MC”. New Zealand military service records reveal that that serial number belonged to Private John Godwin Garland of Auckland, a medical orderly who from December 1915 to October 1916 served on board the NZ Hospital Ship Marama. Although Russell’s letter writer may have been a real person, the claims made in the letter as published by Russell cannot be verified and are inconsistent with the available evidence on insurgent casualties both as to numbers and gender – not one woman is listed among the dead in the list published by Brian Barton in From behind a closed door.

{43} On 5 August 1916, three months after the rising had been put down, a ceremony was held in the Provost’s garden at Trinity College to present the commandant of the Officers’ Training Corps with two large silver presentation cups, each valued at 50 and weighing 170 oz. Silver replicas were to be presented to all ranks of the Corps who participated in the defence of the College as well as to certain other individuals including the colonial soldiers who had assisted. By then, however, Private McHugh was in France, having rejoined the 9th Battalion on 29 July 1916, two days after it had been relieved from the desperate fighting around Pozires. The battalion had been severely savaged during the action and McHugh marched into a badly depleted unit that had lost 17 officers and 299 men during the previous week. Three weeks later, the battalion returned to the front line in the attack on Mouquet Farm but, unlike Private Chapman, his fellow 9th Battalion veteran of the Dublin fighting, McHugh survived the ordeal unwounded, while the battalion sustained further casualties of 5 officers and 158 men.

Ceremony at Trinity College to present silver cups to the OTC and those who participated in the defence of the College.

Ceremony at Trinity College to present silver cups to the OTC and those who participated in the defence of the College.

{44} Nevertheless, three months later McHugh once again found himself on board a hospital ship heading to England after being admitted to hospital with appendicitis. Upon discharge from the 3rd Southern General Hospital on 30 December 1916, he was posted to the 2nd Command Depot at Weymouth. Generally this depot was “for receiving men unfit for return to service within six months and therefore to be returned to Australia”, but that was not McHugh’s fate. In March 1917 he was posted to Wareham where he joined the 69th Battalion, one of the four battalions of the newly-formed 16th Brigade which was intended to be the foundation of a 6th Australian Division. The new formation consisted mainly of men like McHugh who were recovering from sickness or wounds in England. However, the huge losses at Bullecourt and Messines a few months later put paid to the new division, and in September 1917 Private McHugh found himself posted back to the 9th Battalion, though he did not rejoin the unit in France until 22 November.

{45} In the meantime, he had received his replica cup commemorating his part in the defence of Trinity College. In July 1917, while with the 69th Battalion at Hurdcott, Wiltshire, McHugh received a letter from Lieutenant C. L. Robinson, Adjutant of the Trinity College OTC, advising him of the cup and requesting an address to which he might send it. Hoping to wheedle a bit of leave in Dublin, McHugh replied:

I am to get a few days leave to proceed to Dublin and my Colonel is not the kind of man to grant leave without he has a reasonable excuse put before him.

Now just between you and I Sir I wish you would do me a favour by dropping me a line stating that you should like me to be present at your OTC to be presented personally with this cup.

If you could do me such favour Sir I would be very thankful to you.

{46} He must have thought his chances slim because he added an address to which the cup might be sent in the event that it was to be posted. In a letter dated 23 July Robinson confirmed the bad news, and on 1 August McHugh wrote back acknowledging receipt of the cup and advising that he would call on him personally when he went on leave. Whether he in fact received his Dublin leave and returned to Trinity College is not known.

An “Australian officer … on leave in Ireland”

{47} Another Australian in Dublin during Easter Week wrote of his experiences in a letter to Richard Garland, the general manager of the Dunlop Rubber Co. The text of the letter was published in the Age newspaper on 1 July 1916. The Age did not name the soldier but described him as an “Australian officer … on leave in Ireland” who had offered his services when the rising broke out.

{48} The letter describes a series of events in which members of the Crown forces committed atrocities against Irish civilians. Without admitting any personal part in killing or wounding innocent civilians, the tone of the letter suggests, at the very least, indifference rather than outrage at the conduct the “Australian officer” witnessed:

They called for bombers and I was turned over to a captain, an enormous man about 6 feet 4 inches. At 10.30 am we went, with fourteen others, to attack a shop. Martial law had been declared. Near the barracks we saw three men. The captain wanted to know their business, and one answered back, so the captain just knocked him insensible with the butt of his rifle. The other two ran and one shouted something about “down with the military” and the captain just shot him dead. When 100 yards away from the suspected shop I advanced alone with bombs ready. There was a tram in front and I crept up to it and dashed round, putting in a bomb at short range through the front window. It did a lot of damage, and I then went straight through the window, followed by the others. There was a light showing from a room downstairs. I went down carefully, and told the people there to put up their hands, just allowing them to see a bomb I was holding. This had the right effect, and I went down and found five men and three women. They were marched to the barracks. Two were let go. The three others turned out to be head men of the gang and were shot.

{49} The letter provoked a strong reaction in Australia, particularly from Irish Catholics who were already incensed by the British Government’s methods of suppressing the rising and the execution of its leaders. Catholic newspapers published comments highly critical of the Australian officer’s conduct. One correspondent to the Tribune, a Melbourne Catholic newspaper, wrote:

As a specimen of cold-blooded atrocity I venture to say that the Hun in his worst alleged excesses has not equalled it. … The letter of this “Australian officer on leave”, which is a disgrace to Australian manhood … stirs up rebel instincts that I thought had perished.

{50} The correspondent’s hyperbole illustrates the passion which the letter aroused. And it was not only Catholic newspapers and their readers that were outraged. A few months after the rising, the socialist activist D. P. Russell republished the letter in his pamphlet Sinn Fin and the Irish Rebellion, adding the comment:

Did Australia’s sons in Dublin add lustre to the deeds of the heroes who fought and died in Gallipoli for the “Rights of Small Nations”?

{51} Today, more than eighty five years after the event, the letter’s callous tone still retains its capacity to shock, even if it no longer stirs up rebel instincts. Yet, a reader today with a detailed knowledge of the rising is more likely to be intrigued by the similarity between the incidents the letter describes and the events leading up to one of the most notorious episodes of the rising – the murder by Captain John Bowen-Colthurst of a prominent newspaper journalist, Francis Sheehy Skeffington.

{52} According to Michael Foy and Brian Barton, authors of The Easter Rising, Sheehy Skeffington was

a well-known, loved and somewhat eccentric Dublin character dressed in a knickerbocker suit who was actively involved in every worthy cause such as pacifism, socialism, vegetarianism, alcohol abstinence and votes for women. He had become an object of resentment in military circles because of his opposition to the war which the authorities believed hindered recruiting.

{53} Bowen-Colthurst, of an Anglo-Irish family from County Cork, was a captain in the 3rd Battalion of the Royal Irish Rifles stationed at Portobello Barracks. An honours graduate from Sandhurst and a veteran of the Boer War, India and Tibet, he had taken part in the Battle of Mons in August 1914 and had been severely wounded at the Aisne the following month, leading to his being invalided home. He had appeared before a medical board in March 1915 but had not been returned to the front, due more to an adverse report as to his competence written by his commanding officer than to his medical condition. Lieut.-Colonel W. D. Bird (later Major General Sir Wilkinson Dent Bird) had accused Colthurst of attacking a German position at the Aisne without orders, thereby leading to a counter-attack that resulted in the battalion’s suffering many casualties, including Colthurst himself. Bird had also accused him of breaking down during the fighting. Colthurst denied Bird’s charges, arguing that Bird had a personal vendetta against him because of an argument the two men had had in 1914 after Bird had offered the regiment for service in Belfast to enforce the Home Rule legislation. Colthurst later wrote, “[H]is crowning folly was volunteering the services of the Royal Irish Rifles he commanded for active service in Belfast and Ulster. … I as an Irishman declined to give my men orders to fire, on the peaceful citizens of Belfast.”

{54} With the outbreak of the rising, Bowen-Colthurst once again found himself in action. On the morning of Wednesday, 26 April 1916, he transferred three prisoners, Sheehy Skeffington and two other journalists, Thomas Dickson and Patrick MacIntyre, from the barracks guardroom to an adjoining yard where he ordered a party of seven soldiers to shoot them, which they did. Were it not for the persistence of a fellow officer in the Royal Irish Rifles, Major Sir Francis Vane, the murders might have been hushed up. Colthurst had his supporters and to them he had simply done his duty under difficult circumstances. In her diary of the rising, Elsie Mahaffy wrote of Colthurst in glowing terms: “one of the best young men I have ever met” and described Skeffington as “a man whose life and principles were vicious” and the other two shot with him as “ruffians, editors of sedition & indecent papers”. But Vane took the matter to the top, laying his allegations before the Secretary of State for War, Lord Kitchener, who ordered that Bowen-Colthurst be arrested and charged.

{55} On 10 June 1916 a General Court Martial found Bowen-Colthurst guilty of the murder of Sheehy Skeffington and the two other men. But the court also found he was insane at the time he committed those acts. It was largely the evidence of Major General Bird as to Colthurst’s behaviour in France that persuaded the court martial that Colthurst was mentally unsound. Therefore, instead of being hanged for the murders, he was detained in Broadmoor criminal lunatic asylum at His Majesty’s pleasure. This lasted less than two years, until January 1918, when Colthurst was granted conditional release. On 26 April 1921 – five years to the day after the murder of the three journalists – Colthurst, with his wife and four children, emigrated to Canada, where he resided until his death on 11 December 1965 at the grand age of 85 years.

{56} Public opinion was not assuaged by the court martial and eventually the Government established a royal commission under the chairmanship of Sir John Simon to inquire into the murders. The commission took evidence between 23 and 31 August 1916 and issued its report on 29 September that year. It is difficult to establish from the published accounts of the evidence before the court martial and of the evidence and report of the royal commission precisely what occurred, as the testimony of the witnesses is often inconsistent. Nevertheless, subject to a few discrepancies, the events described in that material bears an uncanny resemblance to those to which the “Australian officer” referred in his letter.

{57} The episode began on the evening of Tuesday, 25 April 1916, when Sheehy Skeffington was walking toward his home in Rathmines from a meeting in the city, which he had convened to discuss ways to prevent the looting that had broken out in Dublin following the break down of law and order. As he approached Portobello Bridge, which spans the Grand Canal not far from Portobello Barracks, he was being followed by a small crowd who were making a noise and heckling the odd-looking eccentric. Lieutenant Morris, who was in command of a detachment of troops guarding the bridge, detained Sheehy Skeffington and brought him into the barracks. Bowen-Colthurst then took charge of the prisoner and searched him, but found nothing of an incriminating nature. Nevertheless, Sheehy Skeffington was detained in the guardroom.

{58} Later that night Bowen-Colthurst was given command of a patrol whose task was to enter and occupy the shop premises of a suspected Sinn Fin sympathiser Alderman James Kelly at the corner of Camden Street and Harrington Street, about a kilometre from the barracks in the direction of the city. On his way out of the barracks at about 10.30 pm, Bowen-Colthurst removed Sheehy Skeffington from the guardroom and forced him to accompany the patrol as a hostage, threatening to shoot him if the party were fired upon. The patrol left the barracks and proceeded along the lane that leads from the main gate of the barracks to Rathmines Road. This is where the evidence given to the royal commission and the events described in the letter of the “Australian officer” begin to coincide.

{59} As the patrol turned into Rathmines Road, it came upon three men by the name of Coade, Keogh and Byrne. Byrne later gave evidence to the royal commission that they had been at a sodality meeting at the nearby Catholic Church of Our Lady of Refuge. Byrne’s evidence continued:

Coade was smoking a cigarette when the officer came forward and asked what they were doing out at that hour of the night, and if they did not know martial law had been proclaimed. Witness said they did not know. The officer turned to a soldier and said “Bash him”. Coade was then struck with the butt-end of a rifle. … They then separated, Keogh going off on his bicycle one way, and Coade and witness in the opposite direction. Then witness saw a flash and heard a report, and looking back he saw that Coade had fallen.

Rathmines Road near the entrance to Portobello Barracks where Captain Bowen-Colthurst shot Coade. The dome of Our Lady of Refuge Church is in the centre of the photograph.

Rathmines Road near the entrance to Portobello Barracks where Captain Bowen-Colthurst shot Coade. The dome of Our Lady of Refuge Church is in the centre of the photograph.

{60} The patrol continued along Rathmines Road to the Portobello Bridge where Bowen-Colthurst divided the party into two. Leaving one half of the men at the bridge under the command of Lieutenant Leslie Wilson, he took the rest forward to attack Kelly’s shop. Sheehy Skeffington remained with Lieutenant Wilson.

{61} What happened thereafter is described by Miss Kelly, Alderman Kelly’s sister, who gave evidence to the royal commission:

The military threw a bomb into the shop, and the shop assistant was wounded by it. The door had been closed, and it was forced open by the soldiers with their bayonets. When the soldiers entered they looked for the telephone, and she was going to show it to them when she heard an officer say: “Now lads, another bomb for upstairs.” The bomb, however, was not thrown, for she saw that officer coming downstairs with the bomb in his hand. The officer shouted to those in the house, “hands up”, and said: “Remember, I could shoot you like dogs. Martial law is proclaimed. I am an Irishman myself. We have shot persons on the street before we came in.” The lieutenant confirmed that by saying: “We have done it.”

{62} Lieutenant Wilson in his evidence at the court martial said, “Captain Colthurst came back with five prisoners, including Messrs Dickson and MacIntyre. Two prisoners were allowed to go away, and two were taken into the guardroom.” The patrol then returned to the barracks where Sheehy Skeffington, Dickson and MacIntyre were locked up for the night. The next morning Bowen-Colthurst ordered the three prisoners to be shot.

{63} The similarities between these events and those described by the “Australian officer” are striking. Yet there are differences. For instance, the letter describes the three men who were shot as “head men of the gang”, whereas the royal commission cleared the three journalists of any involvement in the rising. However, Bowen-Colthurst had written in his report of the incident that he knew them to be “dangerous characters”, subsequently describing them as “leaders of the rebels”. Presumably he did so to provide some justification for his actions. The “Australian officer” might therefore have been relying on the self-serving rationalisation that Bowen-Colthurst was himself retailing, or might have been repeating the talk that was current in Dublin at the time. For instance, on Friday 28 April 1916, Mary Louisa Norway (the wife of Arthur Hamilton Norway, the secretary of the General Post Office who was often at the Castle during Easter week) wrote in a letter: “On Wednesday three of the ringleaders were caught, and it is said they were shot immediately!”

{64} Nevertheless, there are other discrepancies between the letter and some of the accounts of the events of that night. Most are within the normal bounds of variance that occurs when eye-witnesses describe an incident. But the most significant discrepancy between the account in the letter and the events surrounding the raid on Kelly’s shop falls outside that normal variance. The letter gives the time of the patrol as 10.30 am, while all other accounts place the raid as having occurred at night. Although the evidence as to precisely when the patrol left the barracks is not totally consistent, most accounts suggest that it would have been about 10.30 pm. Therefore, what on its face is a disqualifying discrepancy might simply be the result of an error in the writing or the transcription of the letter – a substitution of “am” for “pm”. Furthermore, after describing the raid and the shooting of the three men, the letter continues “Anyone out after dark was shot.”

{65} Similar considerations might explain another significant variance. Whereas the letter describes the party as consisting of a total of sixteen men (being the letter writer, the captain and fourteen others), the royal commission evidence indicates a larger party – probably forty. Again the figure of fourteen in the letter might be the result of an error in writing or transcription or, alternatively, the writer might have been referring to the number who actually attacked Kelly’s shop, as opposed to the whole group – one half of whom remained at the bridge under Lieutenant Wilson.

{66} Apart from these discrepancies, the coincidence between the events described in the letter and the evidence of what happened on the patrol to Kelly’s shop is so close that it would be remarkable if they described different incidents. True it is that there were many occasions when British soldiers shot and summarily executed civilians during Easter week, and after the rising the British did officially execute fourteen of the Dublin insurgents by firing squad. But, apart from the Bowen-Colthurst affair, there is no account in the literature of an incident involving three men being captured, imprisoned and shot in circumstances similar to those described in the letter. It is possible that it did happen and was covered up; but on the publicly available information concerning the activities of Crown forces during the rising that possibility is mere speculation.

{67} It is also possible that the letter was a fabrication – a fictionalised account based on the events of the Bowen-Colthurst affair but given a local flavour by the inclusion of an Australian officer, perhaps to inflame Irish-Australian readers at a time when sectarianism was on the rise. But such an explanation beggars belief. Although the letter writer is unnamed, the letter itself was identified as having been sent to Richard Garland, presumably by someone known to him whose veracity he trusted sufficiently to make the letter publicly available. Garland, an Irish born Canadian, was a senior official of a significant public company, and apart from a prejudicial view of his origins there is nothing to suggest he had a motive or the propensity to forge the letter, or to be a party to such a hoax on the Australian public. But even more telling is the fact that it was published on 1 July 1916, nearly two months before the royal commission convened. Even though this was after the court martial, the events at Kelly’s shop and the shooting of Coade did not form part of the evidence at Bowen-Colthurst’s trial. If the letter was a hoax, the hoaxer must have been well informed.

{68} Nevertheless, the identity of the “Australian officer” remains a mystery, and until that can be ascertained the letter’s authenticity cannot be categorically established. One piece of evidence that is troubling is a list containing the names and units of officers who reported at Portobello Barracks during Easter week. The list, which is in a War Office file covering the inquiry into the deaths of the three journalists, does not include any Australian officer. However, the identification of the letter writer as an “Australian officer … on leave in Ireland” comes not from the text of the letter itself but the newspaper’s introductory comments. Should it be the case that he was not an officer, then there is yet another link between the events described in the letter and the evidence given to the royal commission. Lieutenant Leslie Wilson was a key witness at the royal commission. He was on the patrol the night of the raid, being placed in charge of the party that stayed at the bridge. In the notebook that Sir John Simon kept during the royal commission there appears the following note of Wilson’s evidence (which does not appear in the extracts published in the 1916 Rebellion Handbook):

Colthurst had with him a man who carried bombs. I don’t know what regiment. Party consisted mostly of R[oyal] Irish Rifles.

I heard Capt Colthurst ask if any man was efficient bomber. One man came forward.

{69} The “Australian officer” in his letter had written: “They called for bombers and I was turned over to a captain, an enormous man about 6 feet 4 inches.” Once again the coincidence is remarkable, particularly given that Colthurst was about 6 feet 4 inches (193 cm) tall. Both accounts of the recruitment of the bomber suggest a degree of subordination that implies that he was not an officer. This makes sense given that an officer, whose role is to lead and direct, is unlikely to have been appointed the raiding party’s bomber. And who would be better suited to that role than a soldier who had acquired his bombing skills in the trenches of Gallipoli? Furthermore, Wilson’s inability to recognise the bomber’s regiment is consistent with the man being from a force outside the British Army.

{70} Monk Gibbon, a lieutenant in the British Army’s Service Corps, was at Portobello Barracks during Easter Week. In his war memoirs, Inglorious soldier, he wrote of the Colthurst affair and “the tall bomber” whom he met the morning after the raid on Kelly’s shop. Gibbon formed a more favourable impression of the man than Russell or the correspondent to the Tribune, whose opinions were based solely on the letter. Expanding on a brief note he had made in his diary, which included “Pot shots at windows. Bomber knocking up his rifles”, Gibbon wrote in his memoirs:

It appears from this that whenever Colthurst, out on patrol, saw a figure at a lighted window he promptly fired; and that, but for the bomber’s action, a quite innocent person might have been killed. … He [the tall bomber] was lost in admiration of Skeffington’s behaviour. “He was just wonderful, sir. I never heard a man talk like that before. And he showed no fear, no fear at all.”

Everything the young NCO said made me wish to meet this man who had won such respect and admiration from one member of his escort.

Attitudes to the Easter rising

{71} As remarked above, the diary of Private Chapman is lacking in detail about his activities in Dublin during Easter week. It also does not tell us what he thought about the rising or his part in its suppression. He was already an experienced soldier, having been on active service at Gallipoli. Yet street fighting against civilian insurgents would have been a completely different kind of war for him. As a soldier, he no doubt did his duty, but whether he felt any concerns about fighting the Irish insurgents is not disclosed. Chapman was not a Catholic; he was Presbyterian. Whether his religion contributed to his attitudes to the rising can only be a matter of speculation. Certainly, Private Davis, a Methodist, was not happy about what he was asked to do. He recorded in his diary: “We were in a very unenviable position, for we personally had no quarrel with the rioters.” But as a pragmatic Australian soldier he did his duty: “We are making the best of a bad job, but would prefer to be anywhere but in this unenviable city.” Private McHugh was a Catholic of Irish descent, but it seems he, too, did his duty. Whether he shot the dispatch rider who passed by Trinity College is not known, but by all accounts he would have been on the roof of the College when the event occurred. What he felt about being called to arms by the British military authorities and ordered to fight his cousins has not been recorded, and on his return to Australia he does not seem to have spoken much about it, if at all. Members of his family, who still live in North Queensland, were unaware of “Uncle Mick’s” adventure until told about it in 2002.

{72} But being Irish, or a Catholic, did not necessarily translate into sympathy with the insurgents or their cause, let alone a propensity to disobey an order to fight against them. When the rising broke out, a majority of the 2,400 British Army soldiers in Dublin were Irishmen, mostly from regiments that recruited in the south of Ireland. It was these Irish troops that initially confronted and fought the insurgents. It was not until reinforcements from the 59th (North Midland) Division began arriving in the city on the Wednesday that the Crown forces assumed a predominantly English composition. John Dillon, the Irish Party MP who was in Dublin during Easter week and witnessed events there, told the House of Commons:

I asked Sir John Maxwell himself, “Have you any cause of complaint of the Dublins [the Royal Dublin Fusiliers] who had to go down and fight their own people in the streets of Dublin? Did a single man turn back and betray the uniform he wears?” He told me, “Not a man.”

{73} Irishmen in the British Army, including nationalists who before the war had been in the paramilitary Irish Volunteers, had already made a commitment to serve the Empire and reject the arguments of the separatist nationalists that they were traitors to Ireland and degenerates for having taken the king’s shilling. Attempts by the German Army to incite disaffection among the Irish regiments on the Western Front in the wake of the rising were met by derision and defiance. Keith Jeffery has written:

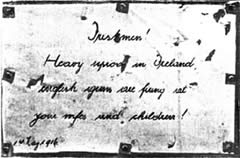

During May 1916 the 8th (Service) Battalion of the Royal Munster Fusiliers … found themselves faced by two German placards. One read “Irishmen! Heavy uproar in Ireland. English guns are firing at your wifes [sic] and children.” The other announced the fall of Kut to Turkish forces. According to the regimental history (not an entirely unbiased source) the men responded by singing “God Save the King” and captured the placards which were later presented to King George V

German sign taunting Irish troops over the rising.

German sign taunting Irish troops over the rising.

{74} Some Irishmen, like the nationalist intellectuals Tom Kettle and Frank Ledwidge, were troubled by their choice, but nevertheless considered that by enlisting in the British Army they were serving Ireland and the cause of Home Rule. It was only after Pearse had surrendered and the British began to execute the leaders that the insurgents of Easter Week started to assume the mantle of Irish heroes. In the early days of the rising, they were largely seen as wreckers who had stabbed Ireland in the back.

{75} It is also the case that the rising was unpopular with those sections of Dublin’s inhabitants who were dependent on the separation allowance paid to them while their husbands were serving in the British Army in France, either as regulars or as recruits to the New Army. Many of them feared the rising would threaten their economic well-being. Others had lost loved ones during the Gallipoli campaign, which saw the slaughter of the Dublin Fusiliers at V Beach on 25 April 1915 and the destruction of the 10th (Irish) Division at Suvla Bay in August. To many of them, the rising was an insult to the memory of those who had died fighting for the Empire.

{76} It is not surprising, therefore, that the immediate response of Australian Irish to the rising was generally negative, both in Australia and at the front. Even Archbishop Mannix initially described the rising as deplorable and its leaders as misguided, a sentiment shared by Sergeant James Joseph Makin of the 21st Battalion, a Catholic, who wrote to his mother:

Is it not deplorable that trouble has broken out in Ireland? It is astounding, in as much as there are thousands of fine men in the Irish regiments here, who are moved by the highest sense of patriotism. Who can deny that these Irish regiments are not among the best of the British fighting units and are fighting to uphold British integrity and traditions? I have mixed with them for a month and I know their spirit. And yet they are having their honor and name filched away by a ruffian horde, blinded by long-past wrongs and kindled by German gold and influence. Let me hope that the trouble will be stamped out this time for good and all, as assuredly it will be, but at the expense of much needed lives at a critical moment. This is another instance illustrating the saneness of the “Keep your eye on Germany” policy.

{77} The reference to German gold and German policy reflected a widespread belief at the time that the rising was instigated and financed by Germany to distract Britain from the war effort. An intelligence summary issued by General Headquarters Egyptian Expeditionary Force on 28 April 1916 included the following:

The capture of the notorious SIR ROGER CASEMENT and two German officers (on the very day when the disturbances broke out) whilst being landed off the Irish Coast from a disguised German Auxiliary cruiser has probably robbed the rebellion of all direction. … Inspired articles have already appeared in the Dutch and Italian papers which show clearly that this rebellion has been organized in Germany to co-incide with the approach of the spring when an Allied offensive was to be expected, and also relied [sic] to find in Ireland (excused from the Military Service Act) many men of military age who could be used to further the designs of the enemy.

{78} Casement had, in fact, been arrested on the preceding Friday, after he had come ashore with two Irishmen, Bob Monteith and Dan Bailey. Ironically, his mission had been to persuade Pearse and Connolly to call off the rising because of the lack of German support. Nevertheless, the intelligence report is indicative of the belief that the Germans were behind the rising, a view that had currency well before Easter Week. An Australian officer from the 9th Light Horse had written home in November 1915 that while in Ireland on convalescent leave he had seen “a full battalion of ‘Sinn Feiners’ at Limerick dressed in German uniforms and armed with Mausers.”

{79} Yet Australian soldiers drew a distinction between Sinn Feiners and the Irish soldiers with whom they had served at the front. In a letter to his father, Sergeant Makin wrote:

It is pleasing that the Irish rebellion is not as alarming as it was thought and is now dying out. It is most regrettable that it should have occurred at this time. It is the fanatical Sinn Feiners at the bottom of the trouble, & the Nationalist Party under John Redmond is absolutely against them. It is astounding when you see the Irish regiments here in France, fighting along with the rest of us: – Australians, N.Z.ers, & Canadians.

{80} Makin’s references to the Irish regiments and the unity of purpose of the Empire soldiers touches on one of the key issues that divided constitutional nationalists from the separatists: the idea that one could serve severally the country of your birth and the Empire at one and the same time – a view shared by most Australians, though not all. Ironically, in Australia it was not nationalists but Empire loyalists who opposed the notion of dual loyalty, believing that the Empire was one and indivisible.

{81} The attitude of many Australian soldiers to the rising was probably summed up by Private John Collingwood Angus of the 28th Battalion who, in a letter to his sister on 5 May 1916, wrote:

things seem to be pretty lively in Ireland just now, well I wish they would send some of our boys there we would make things hot enough for them rebels in a pretty short time.

Conclusion

{81} How many Australian soldiers were in Dublin during Easter week 1916 is not known and may never be known – given that AIF records which might provide such information were destroyed in the late 1950s, when staff of the Australian War Memorial culled what they then considered to be superfluous material. While records in England and Ireland provide information about the rising and in some cases about individuals, such as Private McHugh and the anonymous Australian soldier, they do not include a list of names or even a return of the numbers involved.

{82} Nevertheless, it is reasonable to assume that there were more than the handful whose stories are told here. Although by April 1916 the AIF had only just moved from Egypt to France and its administration was still in the process of transferring from Cairo to London, more than 13,000 Australians had by then been sent to the United Kingdom either sick or wounded, who upon discharge from hospital were entitled to convalescent leave. It seems clear that there was not a unit in Dublin as claimed by Tim Pat Coogan – none of the primary or secondary sources supports such a proposition. But Ireland was a popular destination for Australian soldiers, both those officially on leave and others who had absented themselves, either temporarily or permanently from service. Private Davis wrote in his diary that Australian soldiers in England were often harassed by overzealous police who were paid a bounty for every deserter or absentee they caught:

Perhaps that is why most diggers make off to Ireland, and to the furthest places in North Scotland. According to Headquarters’ reports, the number of diggers who have not returned from their furlough is very high – quite a few thousand. Most deserters are reported dressed in mufti and favour Ireland, where they evidently get more sympathy and receive passes and railway warrants.

{83} Certainly, the attractions of Ireland for deserters and absentees was recognised as a problem later in the war, sufficient to justify the Assistant Provost Martial, Lieutenant Colonel John Williams, making a special trip there in April 1918 to investigate the situation. In his report, Williams confirmed what Davis had learned while working at AIF Headquarters two years before. He referred to Ireland as “a perfect haven for absentees and deserters” and described how “‘Sinn Feiners’ and other people … not only harbour absentees and deserters, but provide them with civilian clothes, food, and accommodation, free of charge, in order to hide their identity, and very frequently find them some reasonably lucrative employment.” Williams returned to Ireland two months later with a detachment of military police and made “several arrests”.

{84} So far, only a few of the Australian soldiers who would have been in Dublin during Easter week have been identified. But undoubtedly there were others, like the unnamed Australian treated at Dublin Castle hospital by a VAD who wrote of her experiences in Blackwood’s Magazine. There were also Australian VADs there, who, though not soldiers, had volunteered to assist the Red Cross in treating the sick and wounded during the war. Presumably the deserters and absentees would have avoided joining the Crown forces in suppressing the rising. But for those Australians who did lend a hand, it would have not have been an easy time. They had enlisted and travelled half way round the world to fight Germans, not Irishmen. It was also dangerous work, as attested by Chapman and Davis. But as with so many of the deeds of the diggers during the Great War, one is left wondering what motivated them to do what they did. Veterans of the Dardanelles campaign, who had survived the hell-hole of Gallipoli since the landing, had well and truly lost their thirst for adventure. By September 1915, when Davis, Grant, Chapman and McHugh were on their way to England, morale was low, illness was rife and the glory of war had proved illusory. Men who a few months before had been enthralled by the idea of the great adventure had become envious of the sick and wounded who were being evacuated.

{85} Nevertheless, there was ingrained in these men a strong sense of duty that kept them going, long after their martial enthusiasm had waned. In his graphic portrayal of life on the Western Front, Eye-deep in Hell, John Ellis wrote:

In the war as a whole, on all sides, most men simply did what they conceived to be their duty. When they were told to hold, they held; when told to advance, they went forward even to almost certain death. The reasons for this lay in their sense of patriotism, duty, honour and deference to authority; all much more important concepts than they are today.

{86} More than eighty-five years on, we know a lot more about the rising, its causes and consequences than those in the thick of the action in 1916. But that should not colour our judgment of the deeds of the diggers in Dublin. At the time they would have shared Sergeant Makin’s opinion of the insurgents. And although they might not have liked doing what they were ordered to do, they would have seen it as their duty as loyal soldiers of the Empire to answer the call to arms and “to resist His Majesty’s enemies and cause His Majesty’s peace to be kept and maintained”.

The author

Dr Jeff Kildea is a barrister with a PhD in History from UNSW. He is currently writing a book on Australian soldiers in Ireland during the First World War. His research on the involvement of members of the AIF in the Easter Rising was carried out with assistance from the Army History Research Grants Scheme

References

[1] P. J. Hally, “The Easter 1916 rising in Dublin: the military aspects”, The Irish Sword, vol.7, pp.312-326.

[2] Tim Pat Coogan, Michael Collins: a biography (London: Arrow Books, 1991), p.44.

[3] Roger McHugh (ed.), Dublin 1916 (London: Arlington Books, 1966).

[4] The article is republished as “Inside Trinity College”, pp.158-174.

[5] “Inside Trinity College”, p.161.

[6] “Inside Trinity College”, p.163.

[7] “Inside Trinity College”, p.162.

[8] The diary is republished as “Easter Week Diary of Miss Lilly Stokes” in McHugh, Dublin 1916, pp.63-78.

[9] “Easter Week Diary of Miss Lilly Stokes”, p.66.

[10] Warre B. Wells & N. Marlowe, A history of the Irish Rebellion of 1916 (Dublin: Maunsell & Co., 1916). Wells was a newspaperman employed by the Irish Times.

[11]Wells and Marlowe, A history of the Irish Rebellion, p.154.

[12] Max Caulfield, The Easter Rebellion, 2nd edn (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan, 1995), pp.94-5.

[13] Caulfield, The Easter Rebellion, p.156.

[14] Caulfield, The Easter Rebellion, pp.215-16.

[15] F. X. Martin, “1916 – Myth, Fact and Mystery”, Studia Hibernica, no.7, 1967, pp.1-124. See particularly pp.35-36.

[16] Caulfield, The Easter Rebellion, p.250.

[17] W. J. Brennan-Whitmore, Dublin burning: the Easter Rising from behind the barricades (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan, 1996), pp.116-18.

[18] Brennan-Whitmore, Dublin burning, p.x (Introduction by Pauric Travers).

[19] P. de Rosa, Rebels: the Irish Rising of 1916 (New York: Ballantine Books, 1992).

[20] De Rosa, Rebels, p.330. See Brennan-Whitmore, Dublin burning, pp.84-5 and 116-18, although he does not refer to perforations.

[21] Michael Foy and Brian Barton, The Easter Rising (Stroud, England: Sutton Publishing, 1999), p.180.

[22] 1916 Rebellion Handbook (Dublin: Mourne River Press, 1998). It was originally published in 1916 by the Weekly Irish Times as the Sinn Fin Rebellion Handbook: Easter 1916, with an augmented edition appearing in 1917. It is a comprehensive reference source on many aspects of the rising, providing, inter alia, extracts from official reports and lists of names under various categories.

[23] 1916 Rebellion Handbook, pp.260-1.

[24] Many of the standard accounts of the rising do not mention Anzacs or Australians at all. For example, Thomas M. Coffey, Agony at Easter: the 1916 Irish Uprising (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1971); Owen Dudley Edwards and Fergus Pyle (eds), 1916: the Easter Rising (London: MacGibbon & Kee, 1968); Kevin B. Nowlan (ed.), The making of 1916: studies in the history of the rising (Dublin: Stationery Office, 1969); Lon Broin, Dublin Castle and the 1916 rising (Dublin: Helicon, 1966); M. Dubhghaill, Insurrection fires at Eastertide: a golden jubilee anthology of the Easter rising (Cork: Mercier Press, 1966); Desmond Ryan, The rising: the complete story of Easter Week, 3rd edn (Dublin: Golden Eagle Books, 1957); James Stephens, The insurrection in Dublin, 3rd edn (Chicago: Scepter Books, 1965). Charles Duff, Six days to shake an empire (London: J. M. Dent & Sons, 1966), refers to “some Canadian and other colonial soldiers” being recruited to defend Trinity College, while Michael Taaffe, in a personal memoir, Those days are gone away (London: Hutchinson, 1959), refers to his part in the defence of Trinity College, including service on the roof, without mentioning the Anzacs.

[25] Australian War Memorial (AWM) 1DRL/0197.

[26] AWM PR88/203.

[27] Foy and Barton, The Easter Rising, p.116.

[28] Unless otherwise indicated, the personal details of Private Chapman referred to in this article are taken from the Personnel Dossier of Lt John Joseph Chapman, National Archives of Australia (NAA), Canberra: B2455, CHAPMAN J J. Neither Chapman’s nor McHugh’s service in Dublin are mentioned in the 9th Battalion unit histories – Norman K. Harvey, From Anzac to the Hindenburg Line: the history of the 9th Battalion (Brisbane: 9th Battalion A.I.F Association, 1941) and C.M. Wrench, Campaigning with the Fighting 9th (In and Out of the Line with the 9BN A.I.F.) 1914-1919 (Brisbane: Boolarong Publications for 9th Battalion Association, 1985).

[29] AWM PR88/203. Although described in the AWM database as “copy of diary”, it is in fact a combination of a typescript copy of a series of articles published in the Trundle Star in 1933, which Davis had prepared from the first four books of his diary, and an unedited typescript copy compiled in 1985 from the remaining nine books of Davis’s diary. Although the first part, covering the period 22 December 1914 to 2 December 1916, is laid out in the form of a diary, it is clearly a retrospective account as it contains anachronisms (eg. the use in entries as early as February 1915 of “digger” to describe Australian soldiers when the term had not yet begun to be used) and details of the progress of the war that would not have been known to a private soldier at the time.

[30] Personnel Dossier of 2052 Driver George Edward Davis, NAA, Canberra, B2455.

[31] Unless otherwise indicated, Private Grant’s personal details are taken from the Personnel Dossier of 786 Private Robert Henry Grant, NAA, Canberra, B2455.

[32] Unless otherwise indicated, Private McHugh’s personal details are taken from the Personnel Dossier of 1985 Michael John McHugh, NAA, Canberra, B2455.

[33] Trinity College Dublin Library Manuscripts Department (TCDLMD): MS 2783 Dublin University Officer Training Corps: Reports on the defence of the College in 1916 and correspondence relating to the distribution of silver cups to the defenders, Item 19 Report of Joseph Marshall, Chief Steward, to Major G. W. Harris, Adjt, DUOTC.

[34] TCDLMD, MS 2783, item 58.

[35] TCDLMD, MS 4456 Glen, James A.: His account of Trinity College Dublin in Easter Week 1916, pp.1-2.

[36] TCDLMD, MS 2783, items 32 and 58.

[37] TCDLMD, MS 2783, items 25-27.

[38] TCDLMD, MS 4874/2 Luce, Rev Prof A. Aston Lieutenant, 12th Royal Irish Rifles: Recollections of Easter 1916: memoirs of the defence of Trinity College Dublin during the Sinn Fin rebellion, 14 October 1965, p.2. Luce was ordained in 1908 and served with the 12th RIR from 1915-1918, being awarded the MC in 1917. He was Professor of Moral Philosophy at TCD 1928-49.

[39] TCDLMD, MS 4456 Glen, James A.: His account of Trinity College Dublin in Easter Week 1916, p.2. His reference to “motor dispatch rider” differs from Joly’s and other accounts that refer to the messengers being on bicycles.

[40] 1916 Rebellion Handbook, p.276.

[41] TCDLMD, MS 11107/1, Fitzgibbon, Gerard: Letters to William Hume Blake 1916-1923, Letter 10 May 1916, pp.3-7.

[42] TCDLMD, MS 2783, item 20, George Crawford Acting Porter report to Chief Steward, 26 April 1916.

[43] TCDLMD, MS 2074, Ireland in 1916, an account of the Rising in Dublin, illustrated with printed items, letters and photographs, pp.11-12.

[44] See, for example, Barton, From behind a closed door: secret court martial records of the 1916 Easter Rising (Belfast: Blackstaff Press, 2002), pp.316-18.

[45] D. P. Russell, Sinn Fin and the Irish Rebellion (Melbourne: Fraser & Jenkinson, 1916), pp.70-71.

[46] C. E. W. Bean, The Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918, vol.3: The AIF in France, p.593n.