Internment in Frongach

EASTER 1916, On 15th January, 1916 Michael Collins crossed to Dublin and took a job with the accountants, Craig Gardiners, in Dawson Street. He became a member of the Keating Branch of the Gaelic League where he was friendly with Richard Mulcahy and Gearoid O’Sullivan from Skibbereen who was a teacher in St. Peter’s National School, Phibsboro. He was a regular visitor to the “refugees” – a group of Irish camping in Kimmage who had come over from England to escape conscription.

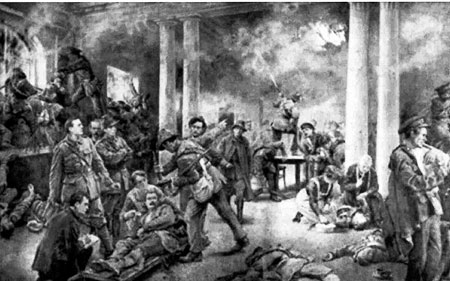

On Friday British guns began to hit the G.P.O. with incendiary shells and, despite valiant efforts to shell it, fire took hold of the building. Volunteers tried to break through the encircling British barricades but failed. In one of those attempts Collins boyhood friend, Sean Hurley was killed. At 4 pm on Saturday 9th April, Pearse issued an order declaring an unconditional surrender “in order to prevent the further slaughter of Dublin citizens and in the hope of saving the lives of our followers now surrounded and hopelessly out-numbered. After their surrender the G.P.O. prisoners were brought to O’Connell Street where later they were joined by those from the Four Courts, then brought in front of the Rotunda Hospital, grouped close together and surrounded by British soldiers with fixed bayonets. While under guard, the officer in charge, Captain Lee Wilson had some prisoners, including the aged Thomas Clarke and his brother-in-law, Ned Daly, hauled before him, stripped naked and publicly degraded. Collins and Liam Tobin witnessed this. Later, in 1920, when it was discovered that Captain Wilson was a District Inspector of the R.I.C. in Gorey, an order for his execution was issued and carried out..

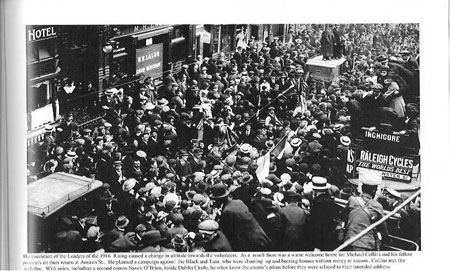

The reaction of some Dublin citizens to the Easter Week rising was hostile and the prisoners, on their way to internment were abused and spat upon, but that was to change quickly. John Dillon of the Irish Parliamentary Party, who was in his family house in Dublin all that week, foresaw the changing mood and advised caution on the British Government. He wrote “the wisest course is to execute no one for the present, and if there is shooting of prisoners on a large scale, the effect on public opinion might be disastrous in the extreme”. The British Commanding officer, General Maxwell, decided to deal with the offenders with the utmost severity. After secret trials fifteen death sentences were carried out between 3rd and 11th May – a long drawn-out period of rising anger in Ireland. In the House of Commons Dillon declared that “thousands of people who ten days ago were bitterly opposed to the whole Sinn Fein movement were now infuriated against the Government” and continued: “It is not murderers who are being executed; it is insurgents who have fought a clean fight.” However, seven hundred and sixty-three influential Dublin businessmen all Unionists, signed a memorandum protesting against interfering with the discretion of the Commander-in-Chief of the British forces in Ireland and the operation of martial law. Henry Asquith, the Liberal Premier, visited Ireland after Dillon’s speech and General Maxwell, who wished to execute the Countess Markiewicz who had played a fighting part in the Rising as “bloody guilty and dangerous”, was ordered to cease all further executions. The poet, W.B. Yeats caught the mood of the nation at this time in his poem, The Rose Tree.

“It needs to be but watered,

James Connolly replied,

To make the green come out again

And spread on every side,

And shake the blossom from the bud

To be the garden’s pride.

But where can we draw water,

Said Pearse to Connolly,

When all the wells are parched away?

O plain as plain can be

There’s nothing but our own red blood

Can make a right Rose tree.”

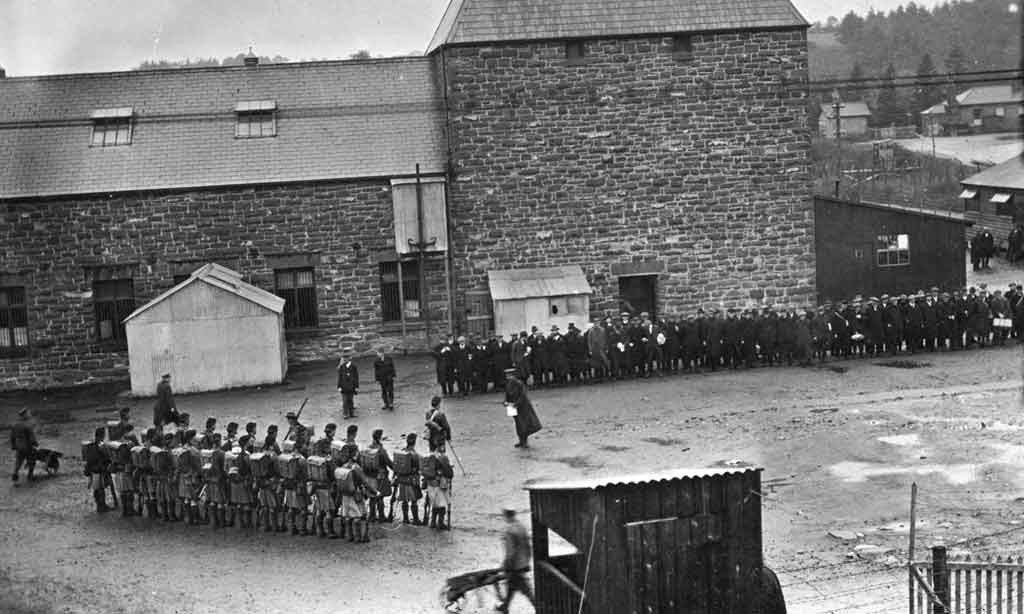

The camp was an old distillery with a number of wooden huts surrounded by barbed wire. Into it were crowded some one thousand eight hundred Irishmen. Some were involved in the Dublin Rising, others were men taken prisoners in Co. Galway after their association with Liam Mellows. A large number were men rounded up because they were deemed by the police to be Sinn Fein sympathisers although, in many instances, the suspicions of the police had no basis in fact.

The dedicated Republicans in the camp separated themselves from the others and formed their own groups from which the I.R.B. formed a nucleus of men dedicated to the national cause. These men gained positions of power and influence over the rest of the camp. Collins was chosen as the leader of Hut no. 10. Much of the prisoner’s time was devoted to reading, lecturers and discussions.

Collins favourite companion was Sean Hales, later to be Vice O.C. of the 3rd Cork Brigade of the I.R.A. There was constant friction in the camp between the prisoners and the soldiers guarding it. The prisoners refused to clear away the refuse from the soldiers’ quarters and were then sent to the North Camp and deprived of privileges. The authorities tried desperately to identify men like Collins, who had worked in England, so that they could be pressed into military service but large numbers of prisoners refused to identify themselves and in only a few cases were the authorities able to identify prisoners deemed eligible for service in the British forces.

Frongoch was the I.R.A. University where, as Batt O’Connor said “many a lad came in a harmless gossoon and left it with the seeds of Fenianism deep in his heart”. The foundations for the policy of resistance in jails and internment camps were laid there. It provided many of the leaders of the I.R.A. during the Anglo-Irish war. Among its prisoners were the aforesaid Batt O’Connor, Thomas Malone, Thomas McCurtain, Terence MacSwiney, Padraig O’Caoimh, Seamas Robinson, Sean Hales and Gearoid O’Sullivan. The camp contained nine hundred and twenty-six prisoners from Dublin and ninety two from Cork, but every county had representatives. Its ex-internees who became T.D.s would later split eventually on the Anglo-Irish Treaty, fifteen voting each way.