London Years

London, 1906—1915.

Michael Collins: A Life –

‘James Mackay’ author

“You don’t know you’re Irish till you leave Ireland”.

TRADITIONAL SAYING

MICHAEL COLLINS WOULD SPEND NINE AND A HALF YEARS, ALMOST a third of his life, living and working in London. Family tradition, followed by all previous biographers, states that throughout that entire period he lodged with Hannie in a furnished flat at 5 Netherwood Road in West Kensington. In fact, Michael and his sister resided at various addresses in West London, and only settled in Netherwood Road in 1914. Hannie, eleven years older than Michael, had passed the Civil Service Open Competition in March 1899 and three weeks later had been appointed a Clerk Second Class in the Post Office. She went to work as a ledger clerk in the Post Office Savings Bank and retired on 15 April I940, having given a life of faithful if undistinguished service in which her only promotion, to Higher Clerical Officer, had come in 1928.’

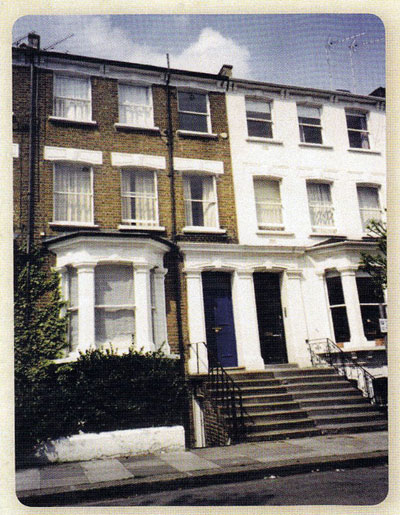

At the turn of the century, on her salary of a pound a week, Hannie had taken a bedsitting-.room not far from her place of work, at 6 Minford Gardens in Shepherds Bush. Her landlord, Albert Lawrence, was a master baker who let out rooms to Scots or Irish clerks and shopmen, but the quiet-spoken girl from West Cork was his favourite and he kept a fatherly eye on Hannie, who touchingly, always addressed him as ‘father’, a habit which Michael easily acquired when he came to London as a Boy Clerk in July 1906. When she got word that her youngest brother was coming to work alongside her, she had asked Lawrence if he could find a room for him. The elderly baker took to the boy immediately, ‘for he was always jolly and sincere”. In 1908 Lawrence moved to Coleherne Terrace, South Kensington, where he opened a bakery on the ground floor and let rooms above. Hannie and Michael moved with him: ‘Don’t think we’re going to leave you, Father,’ said Michael. Lawrence also recalled that ‘There were some fine political arguments n my house. I had an Englishman and a Scotsman as well as other Irishmen living with me, and they would talk politics nineteen to the dozen.’ This cosy arrangement continued until Lawrence retired and sold his business in 1913. Hannie and Michael then moved to a flat at 28 Princes Road, Notting Hill. Eight years later, in Dublin, Michael met Sir William Darling, then on the staff of the British administration in Dublin Castle. They discussed books at great length and discovered a mutual interest in the novels of G.K. Chesterton. It transpired that Michael’s favourite was “The Napoleon of Nottin,g Hill”, Darling concluding that the young Irishman was ‘almost fanatically attached to it’, as he recorded in his memoirs, So It Looks to Me, published in 1952. Early in 1914, however, Michael and his sister returned to Shepherds Bush, renting a substantial flat — two bedrooms, a sitting-room, kitchen and bathroom — on the upper floor of 5 Netherwood Road. The landlords, Willison Brothers, had a dairy on the ground floor. Next door, Henry Brough ran a pharmacy and sub post office. For fifteen years in the 1970s and 1980s the London Irish community tried to persuade the Greater London Council to erect a plaque to Michael’s memory Michael OHalloran, MP for Islington North, had first raised the matter in the 1970s, and latterly Ken Livingstone gave the campaign his backing, but it was not until 1986, when Labour gained control of Hammersmith Borough Council, that the dream became a reality. It was planned to get the newly appointed Irish ambassador to unveil the plaque in April 1987 but due to damage to the terracorta plaque in transit from a pottery in the north of England it was not until 10 July that it was unveiled by Clive Soley. The plaque, mounted high on the wall, bears a facsimile of Michael’s signature with his birth and death dates below. The original idea of including the inscription ‘Irish Nationalist and Soldier’ was dropped and no indication is given on the plaque of who Michael Collins was, other than saying that he resided there in 1914—15. The ceremony was followed by an evening of Irish song and poetry in Shepherds Bush Public Library under the appropriate tide of ‘The Laughing Boy’. The flat latterly occupied by Hannie and Michael was in a typical yellow-brick terraced house; apart from some stucco ornament including mascarons on the window arches, it was no different from countless others thrown up at the end of the nineteenth century to accommodate the vast army of artisans, shop-workers and clerks employed in the metropolis, and nowadays divided into bedsits.

The rooms at Minford Gardens and Coleherne Terrace would have been very similar. In his first year in the Savings Bank Michael’s salary of fifteen shillings a week barely covered the rent and his living expenses though in 1907 Hannie’s salary was raised to £75 per annum. On the basis that two can live as cheaply as one, brother and sister pooled their meagre resources. Inevitably most of the domestic chores fell on Hannie but, devoted to her clever kid brother, she never complained. Early each morning they would leave their lodgings and walk round the corner into Blythe Road, at the far end of which stood the vast red-brick pile of the Post Office Savings Bank. Shortly after Hannie had come to London, this department of the Post Office, which had grown a hundredfold since its inception in 1861, was moved from the City to a site in West Kensington adjoining Olympia. On the very spot where Michael and scores of other clerks laboured daily on the ten million accounts and deposits totalling £200,000,000, a few years previously Buffalo Bill and his cowboys had thrilled multitudes by their daily enactment of the rescue of the Deadwood stagecoach from marauding Indians. The Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII) had laid the foundation stone in June 1899 and the Savings Department completed the move by Easter Monday I 903. Edwardian London was a melting-pot. Thousands of young men and women flocked into the world’s largest city of the time, not only from every part of the British Isles but, increasingly, from the Continent also and farther afield. Although the ethnic mix was not as exotic as it would become forty years later, it was nevertheless a cultural, linguistic and racial maelstrom. Many of the youngsters rapidly became deracinated and acquired the cosmopolitanism and easy tolerance of the typical Londoner of the period. Apart from the Jewish community, largely confined to the Aldgate district in the East End, the one immigrant group which tended to retain its cultural identity was the Irish. Even there, though, the bonds could weaken.

FAMILY VALUES – HIS MOTHERS DEATH

Many a young Irishman, liberated from the claustrophobic constraints of his faith and family, cheerfully abandoned both and assimilated easily marrying a girl who might herself have migrated from Scotland, Wales or the English provinces. If he did not wish to go to Mass on Sunday morning, there was no father (or mother) figure breathing down his neck. If he wanted to read what, at home, had been condemned as ‘bad books’, he was perfectly free to do so. On the other hand, there were many young men and women, cast adrift in an alien environment, who clung together tenaciously and reinforced each other’s Irishness. Things which had been taken for granted at home, or ignored altogether, now became important. If Michael had been tempted by the bright lights and the thousands of blandishments to stray and turn his back on his nationality, there was big sister Hannie at his elbow. He joined the Sinn Fein Club in Chancery Lane and it was in London that he even made his first attempt to learn Irish, attending Gaelic League classes for some time. This first essay into the mysteries of the native language seems not to have progressed very far beyond the ability to write his name Miceal O’Coileain in Gaelic uncials and to make the happy discovery that so many of the words and phrases that peppered everyday conversation in West Cork were, in fact, Irish. In April 1907, at the age of fifty-two, Maryanne died of cancer after a long and painful illness. Her obituary in The West Cork People of 16 April, by ‘one who knew her’ — probably her son-in-law, Pat 0’ Driscoll — included a touching little ode extolling her simple, homely hospitality. She remains a rather shadow figure compared with her husband, yet her influence on Michael was not inconsiderable. It has often been said that the qualities of kindliness and generosity in Michael came from her. Though not as devout as his mother by any stretch of the imagination her son shared her easy-going tolerant attitude to those of other faiths. It is highly significant that, on the night Mary Anne died, it was her Protestant neighbours who were at her bedside, and many others came to her funeral.

Michael himself abhorred the sectarianism which, since the I88Os, had threatened to weaken the cause of Irish independence; in the all-too-brief period allotted to him as head of state he dealt very firmly with any manifestation of partiality or vicrimisation along sectarian lines. Under Hannie’s influence Michael did not kick over the traces, although she must have had some anxious moments. Far worse, in many respects than the temptations of London life in general were the attitudes and outlook of a certain element in the London Irish community which had abandoned the church for the pub and accompanied heavy drinking with a strident anticlericalism. P.S. OHegarty, who got to know him well in the London period left a very perceptive pen-picture of the adolescent Michael: Everybody in Sinn Fein circles knew him, and everybody liked him, but he was not a leader. He had strong individuality, clearly-held opinions and noticeable maturity even as a boy of seventeen when he made his appearance in Irish circles in London. But his place was rather as the raw material of a leader than as a leader.

When he came to London as a mere boy, he fell into spasmodic association with a hard-drinking, hard-living crowd from his own place, and their influence on him was not good. During most of his years in London he was in the ‘blast and bloody’ stage of adolescent evolution, and was regarded as a wild youth with plenty of ability, who was spoiled by his wildness. Not that his wildness was any deeper than the surface. Behind it his mind grew and his ideas enlarged. Michael never lost his faith — that was too deeply ingrained in him — but he went through a phase as he approached manhood when he was decidedly hostile to the Catholic Church. On one occasion in 1909 he caused a furore at a Sinn Fein meeting when he delivered a tirade against the priesthood’s role in Irish history, attacking the spineless attitude of the hierarchy and concluding violently, ‘Exterminate them!’ Despite the advantage of having an elder sister to comfort and guide him, Michael’s immediate feelings on coming to London were homesickness compounded by an immense loneliness. London, with its hustle and bustle and its overwhelming size, was a terrifying prospect for a teenager whose world had hitherto been bounded by Rosscarbery and Clonakilty. ‘Loneliness,’ he once said to Patrick Hodges, ‘can be of two sorts: the delighted loneliness of the traveller in the country; and the desperate loneliness of the stranger to a city’ For many weeks he was thoroughly miserable. The news from Woodfield was far from good; after his departure, Mary Anne seemed to lose the will to live, though in truth her decline was due to a malignant tumour, and nine months later she was dead. Gradually, Michael recovered his equilibrium and found the congenial companionship of Irish boys of his own age. Quite a number, perhaps slightly older, were also employed as clerks at the Savings Bank.

In an organisation of this size, with many hundreds of employees, there was an active social life offering a wide range of sporting, intellectual and recreational facilities. Significantly, Michael did not become involved in any of these. Instead, he gravitated towards the distinctive social milieu of the London Irish. Interestingly, Hannie provided a powerful corrective to the more extreme Irish nationalist tendencies. Her Irishness manifested itself mainly through her regular attendance at Mass and Confession; but she worked alongside mainly English girls and in the years before Michael joined her she had made many close friendships with English families. Through her, Michael was drawn into Hannie’s social circle and thus got to know many English people in a relaxed atmosphere. This social experience was to stand him in good stead years later when he was deeply involved in the critical stages of the negotiations with the British government.

THE GAA AND OTHER INFLUENCES

Michael would lack the awkwardness and the stiffness, perhaps born of a sense of inferiority, that plagued Arthur Griffith. Above all, close contact with the English at work and at home gave Michael a profound understanding of the Ould Enemy. Nevertheless, he was inexorably drawn into a specific section of the London Irish community. It began within months of his arrival when he came to the notice of a group of Irish businessmen in the capital who devoted their spare time and a great deal of their cash to the welfare of young Irish boys and girls working in the strange city. In particular, they organised the distinctively Irish sports under the banner of the Gaelic Athletic Association which had been formed in 1884. Michael, who had never been all that keen on team games, found himself recruited by the Geraldine Hurling Club, and, never having handled a ‘camann’ before, soon took to this Irish brand of shinty with all the zest of a convert. Michael usually played midfield or back. Ned Lynch, who played for a rival team, remembered Michael as ‘an effective though not particularly polished player, a good sportsman as long as the game was fair, but liable to fly into a temper if he suspected foul play. Ever the rugged individualist, Michael tended to dominate his team. Big for his age, tough as nails and loud with it, he polarised the club just as he would the nation. There were those who, even at seventeen, idolised him; just as equally there were those who heartily detested what they regarded as his bullying tactics. In 1908 he put himself forward as candidate for the vice-captaincy of the hurling team. Not surprisingly the election was fiercely contested but Michael won by the narrowest of margins. Once he was on the committee, however, he exhibited qualities of organisation and administration, as well as eloquence and persuasiveness in argument that others found hard to resist. A year later he was elected to the London County Board of the Gaelic Athletic Association, and a few months after that he secured the most powerful position in the Geraldines when he became secretary, a post which he retained until he left London six years later.

The secretaryship came to him at a crucial time in the club’s fortunes, when the initial interest in Gaelic games was on the wane, and there was a move to introduce soccer, rugby and cricket. To Michael, this was rank heresy, and he denounced these ‘garrison games’ by which the British sought insidiously to promote ‘the peaceful penetration of Ireland’. What, one wonders, would he have made of Ireland in the I 990s making a name for herself in world football — and with an Englishman, Jack Charlton, as the national team manager! The controversy split the Association, most of whose clubs seceded, leaving the demoralised Geraldines among the rump. In his first half-yearly report to the club Michael lashed out at the dissension in the ranks: An eventful half-year has followed a somewhat riotous general meeting. Great hopes instead of being fulfilled have been rudely shattered . . . Our internal troubles were saddening, but our efforts in football and hurling were perfectly heartbreaking. In no single contest have our colours been crowned with success . . . In conclusion I can only say that our record for the past half-year leaves no scope for self-congratulation. Signs of decay are unmistakable, and if members are nor prepared in the future to act more harmoniously together and more self-sacrificingly generally — the club will soon have faded into an inglorious and well-deserved oblivion. The following July it was minuted that ‘The Secretary read his report It was not flattering to the members.’ As Michael wrote this minute himself, it shows an uncompromising attitude when he believed himself to be right, even if everyone else was wrong. Significantly, this minute concluded on a triumphant, self-congratulatory note: ‘The report was adopted after the exhibition of marked enthusiasm by a few members.’

Already Michael was attracting a band of devotees who would follow him come what may. One of them was his cousin and old schoolfriend, Sean Hurley, who had now followed him to London. This trait of wanting to have his own way and showing a marked impatience with those who took a contrary view was early evidence of strong will rather than self-will, for in sporting matters as later on in politics Michael sincerely believed that he was working solely for the common good. For this reason he was essentially a realist and a pragmatist, ready to change his mind if he felt that circumstances had altered. This characteristic would be central to his actions a decade later. As Michael reached his majority, the complexity of his character was clearly evident. Those who knew him in the London years paint a picture of a restless young man, a go-getter, whose dynamism was matched by his personal magnetism. Others remembered him ruefully as ruthless, single-minded, domineering and forceful, a man who did not mince his words or suffer fools lightly. He was a driven man, impelled by some sense of destiny, perhaps — but it is easy to say that with the benefit of hindsight. What is clear, though, is that Michael had to excel in anything he undertook, whether it be his clerical work at the Savings Bank or in the promotion of the Geraldines. What made him a bad loser on the hurling field was that he hated to be beaten. In a team game, unfortunately, he had to rely on others, and there were often fierce recriminations when he felt that he had been let down badly. He much preferred sports in which he could compete as an individual. He took part in sports meetings where, in running and jumping, he could pit himself against other athletes. At work and play, Michael approached everything with a manic thoroughness and wholeheartedness. ‘He lived his life with such intensity and at such a power level that the pedestal which he himself had built with his own efforts must never be chipped or even tarnished in any way.”’ Michael Collins, in effect, was a hard act for Michael Collins to live up to, but it explains the strange mixture of bluff geniality and coolness by turns, the extraordinary generosity one moment and the cold calculation the next. When things were going well, especially on the sports field, he would often exhibit a schoolboyish rumbustiousness and a very rough bonhomie which stopped short of hooliganism, but only just. And then his mood would change like lightning and he would be as controlled and self-contained as ever. It is small wonder, therefore, that one of his closest acquaintances from this period would later write: “I can claim to have known Michael Collins as well as, if not better than, most people. Even so, I thought my personal knowledge of him to be no more than surface knowledge. He was a very difficult person to really know”. The clerical work to which Michael was assigned at the Savings Bank was routine and dull, mainly concerned with the checking and issue of dividend warrants and the periodical auditing of passbooks which had to be sent to West Kensington every time withdrawals exceeded a certain limit. The work was relatively simple, and Michael had mastered it within weeks. It is incredible that he stuck it out for four years. At first, however, he had a clear set of goals.

PERSONAL GOALS

There were Civil Service examinations which were the necessary hurdles to promotions and in particular he had set his sights on the newly unified Customs and Excise Service where the prospects were good and the pay excellent. This entailed qualifications in accountancy, taxation, commercial law and economics, so Michael enrolled at the King’s College evening classes.

His reading during this period ranged from Adam Smith to Addison and Locke, the one to give him a broad understanding of economics, the others to improve his style in writing essays. One of the papers he was required to write discussed the British Empire and its future. He wrote passionately about Ireland as England’s oldest colony, acquired by military force and mismanaged for centuries. He concluded on a defiant note: ‘Every country has a right to work out its own destiny in accordance with the laws of its being. . . The first law of nations is self-preservations and let England be wise and not neglect it.

In London, Michael began keeping a little commonplace book in which he jotted down disparate facts and figures, just as he chanced upon them, covering a very wide range of topics. It was all part of the process of self-improvement and it seems to have been undertaken in that same voracious, indiscriminate manner in which he read books. Hannie tried to give some direction to his reading, recommending such contemporary writers as Arnold Bennett, G.K. Chesterton and H.G. Wells. Michael was also an avid theatre-goer, and he both read and saw the plays of Barrie and, above all, Shaw. Significantly his favourite was The Man of Destiny and he copied out passages of it which he carried in his wallet. This led him to read everything he could by or about Napoleon. Did he subconsciously model himself on the young artillery officer who became a general of brigade at twenty-four and First Consul (effectively head of state) at thirty? ‘Centuries will pass before the unique combination of events which led to my career recur in the case of another,’ Napoleon told Las Cases at St Helena in 1821; but exactly one hundred years later history would repeat itself.

One other aspect of Michael that forcibly struck his compatrots in London was his extraordinary clannishness. Even perfect strangers found themselves warmly embraced if Michael detected the Cork accent. If, on the other hand, they hailed from Limerick or Tipperary (let alone points farther east) he would adopt an air of condescension mingled with sorrow. When Robinson’s Patriots was staged in London, Michael went along to boo, because Robinson had dared to suggest that the people of Cork preferred the cinema to a revolutionary meeting. The farther he was from West Cork, in effect, the more intense became his feelings for the place and everything and everyone concerned with it. Often in his mind’s eye he would see the little thatched and whitewashed cottages of Sam’s Cross, or the trim farmhouse up the hill, or Jimmy Santry’s forge.

‘His reading regularly out-distanced his powers of reflection, and whenever we seek the source of action in him it is always in the world of his childhood that we find it.” Once he became an established civil servant, Michael was entitled to two weeks’ annual leave. Invariably he returned home, never pausing to sample the delights of Dublin in passing but going straight from the quay to the railway station for the first train bound to the south-west. Family ties were strengthened when his brother John married Kathy Hurley, Sean’s sister. As the years passed, Michael became the favourite uncle for an ever-increasing tribe of young nephews and nieces. He adored these small children and romped with them like an overgrown schoolboy. It is a great tragedy that Michael never had a family of his own. In an age when people made their own entertainment, ceilidhs were commonplace. Michael, on his own admission, was an indifferent singer, though he took part in the old come-all-ye’s which went on interminably. His forte was the dramatic monologue, his favourite being ‘Kelly and Burke and Shea’ which he would recite with great gusto and appropriate gesture.

According to the contemporary press, relations between Ireland and Britain during this period were, on the surface, fairly satisfactory; but English complacency seemed blind to the realities of the situation. Successive Home Rule bills brought before Parliament by the Liberals had been defeated. On the last such occasion (1893) the bill had passed the Commons, only to be thrown out by the Lords by an overwhelming majority of 419 to 41. Another attempt to settle the Irish question was made by the Irish Council bill of 1907 which was intended to establish a purely Irish body to spend in Ireland the proceeds of Irish taxation. This bill, however, was unacceptable to the Irish people and was withdrawn. Herbert Asquith introduced his Home Rule bill in 1912; again, it comfortably passed the Commons (367 to 267) but was rejected by the Lords. In the interim, however, the Parliament Act of 1911 had ensured that the Lords could not veto bills indefinitely; the bill, if passed in three successive sessions in the same Parliament of the Commons, would automatically become law without the assent of their Lordships. Ireland was seething with discontent at the pusillanimity of Westminster, but there was a new spirit of hope in the air. It could only be a matter of time before Home Rule was secured. Some Irishmen were questioning this never-ending round of going cap in hand to Westminster. Griffith, in the inaugural number of The United Irishman, put the matter in a nutshell: ‘If the eyes of the Irish Nation are continually focused on England, they will inevitably acquire a squint.’ Shortly before he founded Sinn Fein, Griffith also published a tract, The Resurrection of Hungary, in which he outlined the progress of that country to nationhood and suggested that there were useful lessons for Ireland to be learned from this. In the first decade of this century Griffith saw the way ahead by constitutional means. Nationalists would have to gain control of the boroughs and counties through the local elections as a prelude to contesting seats at Westminster.

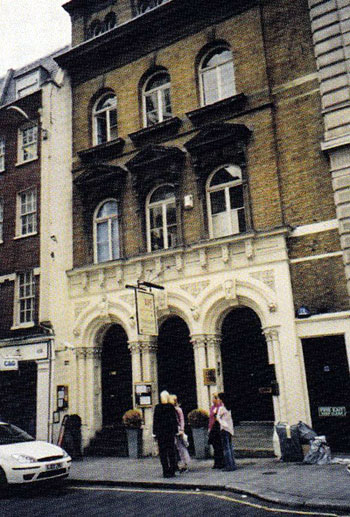

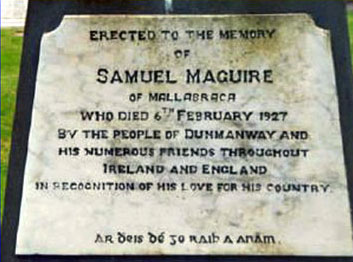

The first opportunity arose in 1907 when Sinn Fein contested the by-election in North Leitrim; although the candidate lost, he polled a creditable third of the votes. In his commonplace book Michael noted that he intended to propose that five shillings be sent from the funds of his local branch of Sinn Fein, with the hope that a further five shillings might be raised at the meeting itself, After the meeting, at which he pleaded eloquently for the financial support of members, he noted triumphantly, ‘Done. £2’, indicating that four times as much had actually been raised. It has not been ascertained when Michael enrolled as a member of Sinn Fein, though he was an enthusiastic attender of meetings from early in 1907 when he was still only sixteen. Of greater importance at the time, and of infinitely greater significance in the long term, however, was his enrolment in the Irish Republican Brotherhood. It will be remembered that Michael John Collins had been a member of the IRB, and it would have been natural for his firebrand youngest son to follow suit. In London, Michael had come to the attention of Dr Mark Ryan, a gentle, scholarly man who was instrumental in rousing the interests of many young London Irishmen in all aspects of Gaelic culture but also infecting them with fervent nationalism. Moreover, one of the older clerks in the Savings Bank was Sam Maguire who befriended Michael and became his mentor. It was Sam who proposed Michael for induction into the Brotherhood, at a secret meeting held in Barnsbury Hall in North London in November 1909.

(Maguire, who died in obscurity, is remembered today in the trophy awarded in the All-Ireland Gaelic Football Championship, known as the Sam Maguire Cup.) This event was a major landmark in Michael’s life; henceforward the IRB would be his consuming interest. He had joined at a time when the Brotherhood was getting a new lease of life, thanks to Tom Clarke, one of the old-style Fenians who, having served fifteen years’ penal servitude for his part in the dynamite campaign of the 1880s, had gone to America. In 1908 he had returned to Ireland and begun to revitalise the movement. Three years later a group of young bloods led by Sean MacDiarmada rallied behind the titular headship of Tom Clarke and gained control of the IRB’s Supreme Council. MacDiarmada gave the movement the impetus needed to place it in the forefront of the independence campaign. Michael rapidly became one of MacDiarmada’s apostles. Within months of joining the IRB, Michael was on the local committee and a year later he was promoted to Section Master; in 1914 he was appointed Treasurer of the London and South England district. Michael’s meteoric rise in the movement is testimony to his tireless energy and drive, as well as to his formidable organisational skills. This was a valuable apprenticeship for the years ahead.

When Sinn Fein was reorganised in 1917 and subsequently embraced all shades of nationalist opinion, it seemed as if the power of the IRB was on the wane and, indeed, there were many who thought that the Brotherhood had gone out of existence. In fact, it continued as the secret society it had always been, wielding immense influence behind the scenes, and would provide Michael with his power base in the crucial years of the Troubles and the civil war. The distrust and even overt hostility towards the IRB was by no means confined to tile Catholic hierarchy; the secrecy and intrigue of the IRB were deeply resented by non-members. Eventually the divergence between Sinn Fein and the IRB would become one of the factors leading to the civil war of 1922 – 23. Probably in 1913 or 1914, Michael gave a paper at an IRB meeting which reveals the political development of his mind, as well as shedding light on the emphasis which, even then, he placed on organisation. Speaking about the various movements that had come and gone, even the early IRB which had declined, he continued: But, by comparison, this revitalised IRB is a vastly different proposition to former movements. In, for example, organisation. Organisation, a lack of it, was chiefly responsible for the failure of several risings of recent times. It is, therefore, of great significance — and of some urgency also — that, if and when the occasion should demand it, the IRB should be even better organised, and so better prepared to meet such an emergency.

A great deal of the organisation will, of course, have to be theoretical — that is the danger. Whereas in practical organisation there is no danger for the element of luck and chance does not enter into it. A force organised on practical lines, and headed by realists, would be of great consequence. ‘Whereas a force organised on theoretical lines, and headed by idealists, would, I think, be a very doubtful factor. Induction into the IRB was a watershed in Michael’s life. Politics now left him little or no time to pursue his studies; and Albert Lawrence states that Michael failed the Civil Service exams ‘because he was giving so much time to those Irish meetings’. Besides, a career in Customs and Excise had lost its appeal. Henceforward Michael would devote himself wholeheartedly to the cause of Irish independence. Everything he did, every book he read, would be in furtherance of this objective. First the studies at King’s College were abandoned, and then in April 1910 Michael resigned from the Post Office Savings Bank to take a more remunerative though hardly more interesting position with Horne & Company, stockbrokers at 23 Moorgate where he was placed in charge of the messengers. Shordy after the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914 he left this firm to become a clerk at the Board of Trade in Whitehall, on the greatly enhanced salary scale of £70—£150 per annum.

In his application he wrote: The trade I know best is the financial trade, but from study and observation I have acquired a wider knowledge of social and economic conditions and have specially studied the building trade and unskilled labour. He also stated that he was proficient at typewriting and double-entry bookkeeping and making trial balances. Interestingly, he gave his date of birth as 16 October 1889 rather than 1890. ‘Perhaps his youthful appearance demanded such redressing of the balance,’ comments Margery Forester but, in fact, the senior clerical position required a minimum age of twenty-four, and at this time Michael was short of the requisite by two months. On 4 August 1914, the very day that war broke out, Michael was at Greenwich Park, Liverpool, playing for London against Scotland in the final of the Hurling Championship of Great Britain. On that fateful day he met one of the Liverpool Irish, Frank Thornton, who would some years later become one of Michael’s most trusted lieutenants during the Black and Tan Troubles. In London, in the years immediately before the war, other men encountered Michael and formed an indelible impression of him. The Shamrock Bar in Fetter Lane off Fleet Street was one of the favourite pubs of the London Irish and it was there that Michael was introduced by Sam Maguire to Peadar Kearney, composer of The Soldier’s Song which is now the Irish national anthem. Kearney would later recall Michael as ‘a tall, good-humoured boy, who gave no indication of the road before him’. Although Irish Home Rule had been a plank in the Liberal platform for many years, the result of the general election of January 1910 (fought on the issue of the People’s Budget which inaugurated the Welfare State) meant that a minority Liberal government could only survive with the support of the Irish Nationalist MPs.

A second election, in December 1910, made little change; the Liberals gained four seats, but this was hardly conclusive and left the Asquith administration as dependent on the Nationalists as ever. Politics entered a new and extremely stormy phase in which militancy was the keynote. Ironically, this was triggered off not so much by the Irish question as the burning issue of votes for women. With so much hostility in the air, so much social, intellectual and political restlessness, the nation hardly noticed at first the slippery slope down which it was rushing in Irish affairs. The Home Rule bill, which Asquith had introduced in 1912, finally passed the House of Commons in May 1914. The bill, which would have conferred limited autonomy on Ireland, was modest in its purpose and fell far short of the outright independence which many Nationalists sought. Because it envisaged a united Ireland, however, it roused the ire of the Ulster Protestants, who reacted violently. Taking a leaf out of their Presbyterian history, they published a Covenant which attracted over 400,000 signatures. At the end of 1912 the Ulster Volunteer Force was founded by Sir Edward Carson and abetted by many prominent figures in both Ireland and Britain. ‘Ulster will fight; Ulster will be right!’ Lord Randolph Churchill had written as far back as May 1886.

Now, almost thirty years later, Carson and his cohorts were reiterating this threat and laying plans for the establishment of a separate government in Belfast should the bill become law. When the bill passed the Commons in May 1914 the Lords (powerless to veto it any longer) tried to amend it by expressly excluding the six counties of North-East Ulster. In July King George himself interceded in a vain attempt to effect a compromise. The bill, in its original form, eventually passed both Houses of Parliament in September 1914, but effectively it was nullified by a simultaneous Act which provided that it should not come into force until after the First World War, the government promising to bring in a bill dealing with the Ulster situation. This bill never materialised. If it was all right for Ulster Protestants to defy the government by taking up arms, then the IRB could do likewise. In November 1913 the Irish Volunteers were called into being by Professor Eoin MacNeill of University College, Dublin, blissfUlly unaware that his paramilitary force, designed purely for the defence of Home Rule, had been infiltrated by the IRB which had a more offensive role in mind. The government, likewise unaware of the separatist tendencies of the Irish Volunteers, allowed the movement to continue drilling; it could hardly suppress it so long as it turned a blind eye to the UVE When the latter obtained 35,000 rifles, several hundred machine-guns and tons of ammunition through the activities of gun-runners operating in and out of Larne with the connivance of the authorities, the Irish Volunteers made their own frantic attempts to procure arms.

On 26 July 1914 a fanatically pro-Irish Englishman named Erskine Childers, a British civil servant who had fought as a trooper in the Boer War and had attained some celebrity from his yachting thriller The Riddle of the Sands (1904), sailed his own yacht Asgard into Howth Harbour and unloaded 900 obsolete Mauser rifles and thousands of rounds of cartridges. Coogan, while researching his own biography, stumbled across a tale that Michael himself had been present on that occasion, and lived in Howth ‘with good-looking girls’.’ Subsequent research revealed that a girlfriend was, indeed, lodging at I Island View, Howth, around that time, but no confirmation of Michael’s involvement has ever been found. The Irish Volunteers swiftly unloaded the precious cargo but on the way back to Dublin were intercepted by the Royal Irish Constabulary, backed by heavily armed troops of the King’s Own Scottish Borderers. A few Mausers were lost in the ensuing scuffle, but the Volunteers managed to get the bulk of their arms safely to Dublin. Unfortunately, a hostile crowd tried to block the police and the military at Bachelors’ Walk. Stones were thrown, and the forces of law and order responded by firing live ammunition at point-blank range into the densely packed crowd. Several people were killed and many more wounded in what would later be regarded as the first outrage in a war that lasted, in one form or another, for nine years. Across the water, the London IRB also raised Volunteer companies. At the end of 1913, when he was still living at Princes Road, Notting Hill, Michael gathered a handful of like-minded young men about him and formed a Volunteer unit.

As a latter-day Napoleon of Notting Hill, it was Michael’s first essay in soldiering. Though proposed by Edward Lee for a captaincy on the strength of this little company which Michael had raised, nothing appears to have come of it, for on 25 April 1914 Michael transferred to Number One Company, London Brigade, being then inducted as a member by his kinsman, Sean Hurley. A close companion of this period was the Irish writer, Padraic O’Conaire; they would drill each week at the German gymnasium in King’s Cross, using reconditioned Martini-Henry rifles and making a weekly contribution towards the cost of the weapons they would one day own personally. This escalation of imminent conflict was accelerated by an incident, a month earlier, at the Curragh, the British Army’s principal base in Ireland, when a number of senior officers dedared their extreme reluctance to take action against the Ulster Volunteers. Inaccurately known to posterity as the Curragh Mutiny, the incident demonstrated forcibly that the government could no longer rely on its own armed forces should it become necessary to coerce Ulster into accepting Home Rule with government from Dublin. The mutineers were led by Brigadier (later General Sir) Hubert Gough who received the written assurance of the Director of Military Operations, General (later Field-Marshal) Sir Henry Wilson that the army would not be thus employed. Both men, incidentally, were Irishmen. The situation was complicated by the existence of yet another paramilitary body in southern Ireland. Following the Dublin lock-out of 1913 (an industrial dispute marred by ugly riots brutally suppressed by the Royal Irish Constabulary), the workers’ leader James Connolly led the Citizen Army, actually formed by a Protestant Nationalist, Captain Jack White whose father was none other than Field Marshal Sir George Stuart White VC — proving that Nationalism often crossed the sectarian divide. On the outbreak of the First World War, Home Rule was put on the back burner for the duration. John Redmond pledged the Nationalists to support Britain in the coming struggle but in so doing he lost control of the Home Rule movement to men who would shordy demand much, much more. Thousands of Irishmen, both North and South, volunteered to fight on the British side for the rights of small nations against German domination. Redmond’s brother would be killed on the Western Front, while Erskine Childers would earn the Distinguished Service Cross with the Royal Naval Air Service before resuming the fight for Ireland.

Meanwhile, Michael continued to work at the Board of Trade by day and drill with the Volunteers by night. The confrontation with the Ulstermen had been postponed, but some day there would be a showdown, and the Irish Volunteers would have to be prepared. For the British Expeditionary Force the government relied on volunteers at first, but after the retreat from Mons in 1914 and the bloody stalemate of Neuve Chapelle in the spring of 19 IS, new recruits were not so ready to come forward. It was then that conscription was first mooted. At a time when it seemed that this might apply to the British Isles as a whole, Michael’s brother Pat wrote to him from Chicago urging him to emigrate to America. ‘If you don’t take a chance you will never get anywhere,’ he wrote. ‘A little nerve is all that’s necessary. Pat also feared — rightly, as it turned out — that England’s difficulty would be Ireland’s opportunity. Just as Wolfe Tone’s rebellion of 1798 had coincided with the French Directory’s plans for the invasion of England, so there could well be a rebellion in Ireland while British garrisons there were depleted. Pat even went so far as to send Katie the money for Michael’s passage to the United States, and he was nonplussed when Michael returned the cash saying that if there were any trouble he would be in the thick of it. This was the first inkling he had of Michael’s clandestine activities. Shordy afterwards, however, in May 1915, Michael resigned from the Board of Trade and took up employment with the Guaranty Trust Company of New York at its London office in Lombard Street. Previous biographers have implied that he took this step in the hope that, if the worst happened, he could get a transfer to the head office in New York, although Coogan has hinted that he may have been ordered by the IRB to seek this position with a view to gaining wider experience of high finance.’ This seems to be arguing from the benefit of hindsight.

All of Michael’s work experience from 1906 onwards would, of course, fit him admirably for his cabinet post of Minister of Finance, but in 1915 it seems hardly likely that this was remotely considered. In any case, the clerical job with the Guaranty Trust was not a particularly responsible or onerous one. After Michael’s death his office manager, Robert Mackey, wrote that ‘the staff, who were privileged to know him, will never believe that he could do an unworthy act’. On the other hand, noted Mackey: ”Only on very rare occasions did his sunny smile disappear, and this was usually the result of one of his fellow clerks making some disparaging, and probably unthinking, remark about his beloved Ireland. Then he would look as though he might prove a dangerous enemy.” Until recendy, biographers of Michael Collins did not present a fully rounded portrait of the man. There was never any reference to activity of an amatory nature. The reader would be left wondering whether there might have been more to those seemingly innocent references to boyish wrestling bouts with close friends, or the doglike devotion of Joe O’Reilly who was his constant companion throughout the last years of his life. It was possible that he was so consumed with politics that he never had time to think of sex. The only writer to touch briefly on the subject was Frank O’Connor, who ingenuously assured his readers that Michael was ‘shrewd enough’ to know about the evils of prostitution ‘only at second hand through the novels of Tolstoy and Shaw’.

Those who were closest to Michael in the London years formed a very different view. His second cousin, Nancy O’Brien, who also worked in the Post Office Savings Bank, saw him frequendy in the pre-war period: ‘All the girls were mad about him. He’d turn up at the cheilidhe with Padraic O’Conaire and would not give them a reck.’ Nancy, who probably knew him as well as anyone, described him as the sort of man that women would either take to instinctively or subconsciously wish to put down. She considered that most of the girls of his own background found him arrogant or overbearing. The nickname of ‘the Big Fellow’ which began to be attached to him in this period was a reference to his swollen head rather than to his physical height. And Coogan has furnished a very shrewd analysis of Irish girls and their attitude towards such a man: ‘In the battle of the sexes, the strong-minded Irish Catholic women have always displayed to a high degree the sexual combativeness of the peer group.’ Coogan also deserves credit for discovering the love in Michael’s life at this period. If Michael might be said to have had a steady girlfriend, it was Susan Killeen from County Clare, who also worked in the Savings Department at West Kensington and shared lodgings with Nancy O’Brien in London and again later in Dublin. Michael probably saw her at the Savings Bank, but contact was developed through the Cumann na nGaedheal socials and dances. Following the outbreak of the First World War she returned to Ireland and worked in PS. O’Hegarty’s bookshop in Dawson Street, Dublin, and it was she who was lodging with Mrs Quick at Howth around the time of the Asgard incident. Susan and Michael were apparently very close while she was in London but after her return to Dublin the affair tapered off. She would upbraid him for not writing more frequendy, and he, in turn, would profess: ‘I really do hate letter-writing, and I’m not good at it and can’t write down the things I want to say — however, don’t think that because I don’t write I forget.’ She would remain on friendly terms with him, although romantically as well as politically they were drifting apart.

In the same letter Michael admitted sombrely that ‘London is a terrible place, worse than ever now — I’ll never be happy until I’m out of it and then mightn’t either’. This black mood was to some extent engendered by the usual squabbling that had broken out among the Irish community. Should the Irish Volunteers follow Captain Redmond’s example and fight in Flanders? Many of them did, under the aegis of Redmond’s renamed National Volunteers; but the rump remained true to their principles and held aloof At a meeting in St George’s Hall, Southwark, when a Redmond nominee was seeking election to office, he concluded his speech with the words describing John Redmond as ‘a man I would go to hell and back with’. From the back of the hall came the voice of a heckler in the unmistakable accent of West Cork: ‘I’d not trouble about the return portion of the ticket.’ Although the principle of voluntary enlistment had not been abandoned, the Derby Scheme, launched in October 1915, aimed at calling up men as they were required, starting with single men. The response to this semi-voluntary scheme proved inadequate, so the government drafted remedial legislation. By the Military Service Act, due to take effect on I January 1916, fUll-blown conscription was introduced. Significandy, it was confined to men resident in Great Britain and did not apply in Ireland where the loyalty of so many young men was suspect. If Michael stayed in London he would be drafted into the British Army, which he saw as a betrayal of Ireland. Besides, he was beginning to hear rumours of renewed clandestine military activity in Ireland, and late in 1915 he went over to find out what was afoot. In Dublin he had a brief meeting with Sean MacDiarmada and Tom Clarke in the latter’s tobacconist’s shop in Great Britain Street near the Rotunda.

The old dynamiter merely looked sharply at Michael over the top of his spectacles and told him to return to London and await further orders. Around Christmas he returned to England and a few days after the Military Service Act came into force on New Year’s Day he attended a Volunteer meeting which had been called to discuss the situation. Liam MacCarthy, a London county councillor, was in the chair and gave his audience the hint that it would be safer if they returned to their native hearth and home. Michael’s response was to give the Guaranty Trust Company a week’s notice, saying that he would not wait for his call-up but intended to enlist right away. Touched by his obvious patriotism, Robert Mackey congratulated him and gave him an extra week’s salary as a parting bonus, which Michael promptly donated to the IRB. On 14 January 1916 he terminated his employment, packed his bags, kissed Hannie goodbye and caught the train for Holyhead. The following day he set sail for Ireland.