Final Journey Aug 1922

Monday 21 August 1922, Michael Collins visits the military installations in Cork city, Ballincollig and Coachford arriving in Macroom in the afternoon. He meets Florrie O’Donoghue and Sean Hegarty, both neutral IRA officers in regular contact with Liam Deasy and other Anti-treaty people, they were helping Collins to stop the Civil War.

A.J.S. Brady in his Autobiography “The Briar of Life” describes the scene when the Convoy arrived in the vicinity of the Hotel in Macroom. A military cavalcade, drawn up on the hotel side of the street, was surrounded by a milling crowd of soldiers and civilians. An eight cylinder Leyland touring car, with an armoured car ahead of it, stood in front of the hotel. I managed to squeeze my way into the premises. The bar at the rear of the shop was packed with military men standing at ease in groups, taking drinks at the long counter. As I looked at them, all clad sprucely in well tailored uniforms with shining brass buttons and polished belts,

Writing now almost fifty-two years later I see Collins as he was that afternoon an impressive, stalwart figure restless with dynamic energy, lithe still, but running to embonpoint. He had taken his military cap off; it was lying crown down on the counter. He was wearing a tunic above side creased breeches and polished brown leggings with boots to match. He raised a hand now and then, and swept back a fallen forelock. His expression in repose had a set look of determination and a shadow of underlying ruthlessness. From the way he glanced constantly around I gathered that he had not yet rid himself of the alertness inherent in a fugitive. Though he certainly cut a dash as a Brass hat, the uniform seemed, in some way, to be out of character with his rebel past.

Dick William’s barmaid Aileen Baker was a merry, comely girl with up-swung, pouting breasts. In the bar that afternoon Collins took her in his arms, carried her to the hall of the hotel, ran upstairs with her, as though she were weightless, and set her standing on the landing. We all clapped and cheered. Collins was laughing as he ran down. He had sensitively mobile features that would momentarily light up in a smile, or cloud in a frown. Collins had a dozen close associates who were known as his Twelve Apostles. I remember the names of three of them: Liam Tobin, Frank Thornton, and Tom Keogh. His aide-de-camp Emmett Dalton had, before dedicating himself to the fight for Irish freedom, served in the British Army during the First World War, and had won a medal for valor.

I saw that the nucleus of an officers’ caste was in being. General Michael Collins was standing at the head of the counter. His aide-de-camp Emmet Dalton was standing beside him. As I pushed my way forward I heard someone saying: “what are you having, Mick?’, “For once in my life I’ll let the old country down,” replied Collins with a smile. “A drop of scotch for me.

As I watched Collins leaving the hotel that afternoon, I heard the cheering, and saw the smiling faces of the milling crowd, but I did not see the shadowy grinning specter in his wake. Next day the twenty-second of August 1922 at BealnaBlath – the “Valley of the Flowers” – County Cork, not far from Sam’s cross where he was born, he ran into an ambush, had his poll shattered by a bullet, and died in the arms of his friend Emmet Dalton. END

NEXT DAY

Tuesday 22 August 1922, 6:16 a.m. Collins leaves Army GHQ in the Imperial Hotel for Bandon, Clonakilty and Skibbereen again taking the Ballincollig, Coachford road to Macroom to deliver supplies to Capt. Conlon in Macroom Barracks. He had further discussions with Florrie O’Donoghue and Sean Hegarty.

Getting to Bandon was difficult. Because of blown bridges and felled trees the Convoy had to detour the bye-roads from Macroom through Toames and Kilmurry villages rejoining the Bandon Road at Crookstown. The Convoy stopped at Longs Pub BealnaBlath for directions to Bandon. Unknown to Collins, senior Irregular divisional and brigade officers had gathered in Murray’s farmhouse overlooking the crossroads for a war council. Those in attendance at the BealnaBlath meeting which had commenced on Sunday 20th included,

Tom Crofts Divisional Adjutant; Con Lucey, Divisional Director of Medical Services; Sean Culhane, Divisional I/O; Tom Hales, Brigade Commandant; Jim Hurley, Brigade Commandant; Tadhg O’Sullivan, Brigade Commandant; Sean Hyde O/C Western Command: Jim Flynn, John Lordan, Brigade Commandant; Pete Kearney, O/C Third Battalion; Tom Kelleher, O/C Fifth Battalion; Dan Holland O/C First Battalion; Mick Crowley, Brigade Engineer, along with, Con Lucey, Sean Culhane, John Lordan, Bill Desmond, Dan Corcoran, C. O’Donoghue, Sonny O’Neill, Paddy Walsh, Sonny Donovan, Jim Crowley, Tady O’Sullivan, Jerh Mahony, Joe Murphy, Richard Galvin, Bill Powell, John O’Callaghan. It is believed that there were in excess of 40 Anti-treaty forces in the vicinity during this war-council meeting and the subsequent ambush. According to Michael Mills Eamon deValera his driver and ADC Denny Crowley Castletownkenneigh, were also in attendance. Liam Lynch (Chief of Staff of the Anti-treaty forces) his second in command Liam Deasy (who was in position D at the ambush site), Erskine Childers and other Anti-treaty headquarter Staff were in the general area at Gurranereagh 4 miles from BealnaBlath cross-roads,

The officer-in-charge was 3rd Brigade Commander Tom Hales who had been appointed by Collins when the Brigades were restructured at a meeting of Battalion officers from the area, held at Kilnadur NS, Dunmanway on January 5th, 1919. Michael Collins presided and Thomas MacCurtain (Murdered Lord Mayor), Commandant of the original Cork Brigade now being divided was present, accompanied by his Brigade Adjutant and Quartermaster. Tom Hales was elected Brigade Commandant: Sean Hales T.D: Vice Commandant; Michael McCarthy, Dunmanway, Adjutant, and Denis O’Shea, Skibbereen, Quartermaster.

This meeting planned for Dunmanway Town was changed to Kilnadur school-house at short notice, It was felt the original location was compromised.

(According to Edward O’Mahony in his book “Michael Collins his life and Times”) A number of I.R.A. officers and men retreating from the fighting in Limerick and Buttevent had arrived at BealnaBlath on the evening before the ambush and joined the group at Bill Murray’s farm house. The sentry on duty at BealnaBlath cross was a local man, by name, Dinny Long. He identified Michael Collins in the military convoy that passed through on the morning of 22nd. August and informed the senior officers at Murray’s.

They in turn informed their commanding officer, Liam Deasy, when, he and de Valera, arrived at Murray’s a short while afterwards. The O’Donoghue document (NLI) shows that the Divisional officers decided in conformity with the general policy of attacking Free State convoy’s to lay an ambush on the assumption that the convoy would probably return later in the day by the same route.

Deasy recounts how he told Dev that an ambush was being prepared for Collins at BealnaBlath after his army convoy had passed the road to Bandon that morning. They expected Collins to return the same way – and not to leave Cork alive. According to Deasy, Dev said: “That would be a pity, because lesser men might succeed him, with whom it could be more difficult to do business.” Deasy does not suggest that Dev tried to persuade him to call off the ambush.

There is a further revealing piece of evidence about Dev. It comes from Dan “Sando” O’Donovan, who told Meda Ryan that Dev was at the meeting the previous night, when the news of Collins’s visit to the area was disclosed. It was decided to lay an ambush on the assumption that he would be travelling to Bandon, the BealnaBlath route being one of only two possible paths. If he travelled that way next morning, they would ambush him on his return, the plan being that Collins would not leave Cork alive. O’Donovan recalled that Dev’s response to this was that it would be a pity, because other people would replace him, with whom it could be more difficult to deal. This was almost exactly the same as Liam Deasy’s recollection of Dev’s attitude.(ref. Michael Mills)

Bill Powell, the ambusher author Meda Ryan (in ‘The Day Michael Collins was Shot) quotes as recalling the meeting at Murray’s farmhouse, named only Tom Hales as expressing reluctance to go ahead with the ambush. He was to command the attack. He had been a very close friend of Collins, who visited him in Pentonville Prison during the treaty negotiations. Collins said he would sooner have Tom Hales on his side than any other man.

Dev left the meeting around 2pm and set out on the journey back to Dublin for the resumption of the Dáil. When he learned the following day of Collins’s death, he is reported to have said: “My God, that is too bad; there is no hope for it now.” He was over-heard by Siobhán Creedon at Walsh’s farmhouse, Clashabee, where Dev had arrived on the evening of August 22 to meet Liam Lynch.

EMMET DALTON REPORT 22nd 1922: He (the Commander in Chief) had two objects in visiting my Command Area, the first being to inspect the Military Organisation and to appreciate the difficulties of the Military problem with a view to giving his advice, and in order that he might more easily render the necessary assistance from General Headquarters, having seen for himself the position.

His second object was of a civil nature. In his capacity as Chairman of the Provisional Government, and Minister of Finance, he was anxious to make every effort to recover some of the thousands of pounds that had been extorted from Banks by the Irregulars prior to their retreat from the city. The stolen money was Excise duties belonging to the Customs and Excise Department, and it amounted to £120,000. They obtained the money by capturing the Official Collector, retaining him, and under threat of force, making him sign the cheques that, of course, the Banks honoured and paid.

Upon his arrival in Cork City at 8.30 P.M. on Sunday the 20th August, General Collins complimented my Officers and I upon the success of our expedition. He then arranged a meal with his relatives (his sister Mary Collins Powell and her family) and other friends in the City. On the morning of the 21st, accompanied by me, he inspected various Military Posts in the city, after which he interviewed several prominent citizens, including the Managers of the Various Banks, in connection with the stolen money. In the afternoon we motored to Macroom where he inspected the Garrison and the Military posts. Then, owing to the fact that the escort armoured car was not running satisfactorily we found it necessary to return to Cork.

He spent two hours in interviewing his friends in the city before retiring he arranged to devote the entire following day to a tour of inspection of the Command Area, as far as Bantry.

Tuesday Aug 22.

At 6.15 A.M. on the morning of the 22nd our little party left my Headquarters (The Imperial Hotel) to commence our tour. The convoy consisted of (research Simon Draper)

Motor Cycle scout – Lt John J Smith(1) Motorcycle Scout

(2) CROSSLEY TENDER driven by Conroy, co/driver Cooney – Comdt Sean O’Connell in Command, Machine Gunners, Gough and Murray, riflemen Pte’s Carmody, Coote, Edmonds, Barry, Caine and one other, the guide was Private John O’Connell (a West Cork native) and a new Army recruit. (A total of Twelve)

(3) LEYLAND TOURER Collins and Dalton sat in the back of a yellow, open-topped Leyland Touring car, loaned to Collins by Gen McCreary on the instructions of Winston Churchill. Two soldiers M Quinn and M Corry shared the driving duties and bringing up the rear of the convoy was the ‘Slievenamon’ (A total of Four)

(4) ARMOURED CAR commanded by Capt Joe Dolan [squad member], drivers Wolfe and Fortune – gunner Sgt Jock Macpeake, (ref. Simon Draper research Cathal Brugha Bks). (A Total of Four)

(Ref. Gen Emmet Dalton) Our first halt was Macroom, because of the extraordinary amount of bridge destruction and road obstruction that had been caused by our retreating enemy, it was necessary for us to take a round-about route, entailing much delay, consequently we made only a hasty inspection, picked up a guide and headed for Bandon. (O’Mahony) The Collins party was informed that the main road from Macroom to Bandon was impassable, as bridges had been destroyed. A local hackney driver, Tim Kelleher, who then worked for Williams’ Hotel and who knew every road in the district, was invited by General Collins to board the Crossley tender and guide them to Bandon. (O’Mahony)

Here General Collins spent some time discussing the position with the officers of the Garrison before proceeding to Clonakilty. (Beyond Beal na mBlath, at another cross-roads, the touring-car became detached from the rest of the convoy but the latter by retracing routes, found Collins standing on the road looking at Newcestown church. The convoy then proceeded, via Tinker’s Cross and Kilbrogan Hill, to Bandon where Provisional Government troops were based with Major-General Sean Hales in command. Here, Kelleher told Collins that he did not know the roads beyond Bandon and that he already had a commitment to take a passenger to Cork for the boat to America that day. Collins thanked him for his work and said “We won’t let you walk back to Macroom and won’t disappoint your friend. We will send you back by car.” He wrote a chit and said, “take that to some man like yourself and he will drive you back to Macroom” (O’Mahony)

Kelleher found a man named Quinn who drove him back to Macroom, actually stopping for a drink at Beal na mBlath; in Kelleher’s case this was lemonade and was all he had that morning since he had missed out on breakfast. Long’s pub was full to the brim with rifle-men. He got to Macroom in time to bring his party to the boat and it was next morning, at breakfast, that he heard of the tragic sequel to the Collins’ journey. (O’Mahony)

(Emmet Dalton) About three miles from Clonakilty we found the road blocked with felled trees. We spent about half an hour clearing the road under the guidance and instruction of, and with the assistance of, General Collins himself. He used a cross-cut saw and a heavy axe with tremendous energy and satisfactory results.

Having cleared the road we proceeded into the town of Clonakilty, which is the hometown of General Collins. He interviewed the Garrison Officer and had conversations with many of his friends, all of whom were delighted to meet him. We had lunch in a friend’s house in the town before setting out for Rosscarbery.

About three miles from Clonakilty we halted at a hamlet in the vicinity of SAMS CROSS:

He orders two pints of the Local Brew known as the Clonakilty Wrestler at his cousins pub the ‘4 Alls’ for the Convoy and his many relatives. He visited the O’Briens his Mothers people who lived locally and there had a conversation with his Brother Sean and family. We spent about a half an hour with these friends discussing domestic affairs, before we proceeded on our journey.

A peculiar circumstance of this journey was, that practically every relative the General had was encountered and spoken to.

Having reached Rosscarbery we consulted with the Officer in charge of the Garrison. before proceeding to Skibbereen where again, in the ordinary Military way, General Collins consulted with the Garrison Officers, listening to their complaints, giving them advice and assuring them on the further co-operation from the Army Authorities.

Skibbereen.

Violet Martin originally from Galway – and subsequently given the pet name ‘Martin Ross’. Was at a wedding in west Cork in the mid 1880’s that changed her life – She met a 2nd cousin Edith OE Somerville from Castle Townshend, West Cork. A couple of years younger – these two ‘cousins’ became ‘inseparable friends and went on to become the famous ‘Somerville & Ross’ pairing of some 40 books. Between 1890 and 1930.. including the famous ‘Irish RM’ series.

Like many Gentry of that time some of the male Somerville’s served in the British army or navy and in the early 1920’s a number of Edith Somerville’s brothers were in the British navy – At this time one of them was on a British war ship off the Cork coast. Clearly ‘Pro-Treaty’ and describing the situation around Drishane in August 1922 Edith Somerville’s diaries show that she and her brother Cameron had a short meeting with Michael Collins in the Eldon Hotel Skibbereen on the morning of 22nd August 1922 – the very day Michael Collins was ambushed/died. Concerned about the way the ‘Anti-treaty’ were raiding and destroying the properties of the gentry and fearing their property would be destroyed the diaries show they met with Michael Collins that morning – seeking additional state troopers for protection. The diaries state that while Michael Collins was sympathetic to their situation but told them he couldn’t help as he had no troops to spare. The Somervilles two of whom were Officers in the Royal Navy returned regularly to Castle Townshend by ships and were put ashore by longboat. Edith Somerville recorded in her diary ‘Cameron, who was woken by the noise, went downstairs, opened a shutter and told them there were no arms in the house. He heard a man say ‘Fire a shot’ but no shot was fired and they seemed to go away. He hastened upstairs to Edith’s room and reported. It was decided to signal the destroyer, as it was hard to say what the raiders would do next. On its captain seeing a red light in Castle Townshend, the agreed danger signal, he turned a searchlight on the house and ‘we knew that our signal had been recognised.’ thus their home was secured from the arsonists’ (1968 biography Maurice Collins).

Due to the fact that it was now about 5 o’clock it was decided not to proceed to Bantry, but to return to Cork by the road which we had taken.

LEAP VILLAGE: There is a story not recorded in any book which tells of the old Lady whose bridge to her farm was blown up, and, as a consequence she was unable to get to the Creamery to sell her milk, She complained to Collins on his way to Skibbereen on that fateful day 22nd Aug. – apparently he made his representations on her behalf to the Co. Council as the following Monday week they (Co. Council workers) commenced rebuilding the Bridge to her home.

Emmet Dalton Continues:- We passed through the towns of Rosscarbery and Clonakilty, then to Bandon where we delayed for half an hour, whilst the General was conversing with several of his friends and two of his cousins who had just returned to the town with the Flying Column. One of the Officers who came from the locality remarked to the Commander-in-Chief that our escort was very small, and that the country we would pass through was much frequented by bands of Irregulars.

His remark was greeted with a confident smile and General Collins said “Where you can go, we can also go.” However, it was soon obvious (to me) that he had carefully noted the remark because he said to me when we were starting off “If we run into an ambush along the way we will stand and fight them.”

Just outside the town of Bandon he pointed out to me several farmhouses which he told me were used by the lads in the old days. He mentioned to me the home of one particular friend of his own, remarking “It is too bad he is on the other side now because he is a damned good soldier.” Then he said “Don’t suppose I will be ambushed in my own County.”

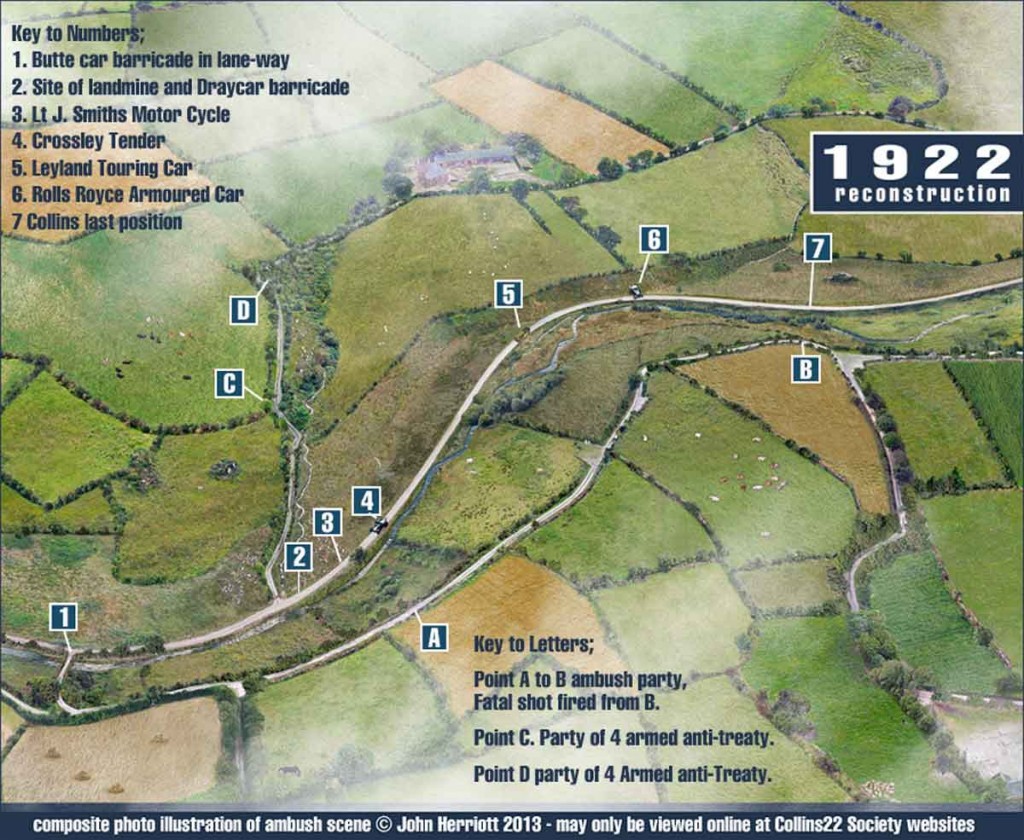

Setting the Ambush (O’Mahony): When Stephen Griffin, the driver of a four-wheel dray from Bandon Brewery called to collect empty bottles from Long’s pub in the morning, his vehicle was commandeered. Griffith was ordered to drive to the selected ambush site. The horse was untackled there, a wheel was taken off and it and the unloaded crates of bottles formed into a barricade blocking the main Newcestown – Crookstown road. Griffith was sent with the horse to the Foley farmhouse at Maulnadruck and instructed to wait. A farm butt (cart) was also commandeered and used to block the boreen on the eastern side of the ambush site.

It was a dry August day until a mist fell as evening approached. Liam Deasy and his adjutant Tom Crofts having returned to Divisional H.Q. in Gurranereagh shortly after the departure of de Valera from BealnaBlath remained at H.Q. for the rest of the day. In the evening they returned to BealnaBlath arriving there about 7 pm. It has been argued by the anti-treaty side that Collins’s tour, accompanied by an army convoy, was deliberately provocative and that the anti-treaty forces were obliged to respond, but Dev and Deasy, at least, must have known of the visit’s peace-seeking aspect.

‘Seamus Robinson, who was Dev’s right-hand man in Bolands Mill and was regularly in touch with Dev, was asked by Collins sometime earlier to arrange talks with Liam Deasy. Collins had indicated that he was anxious to meet the three Toms, (Malone in Portlaoise Jail, Barry in Kilmainham Jail and Hales was in West Cork). It would be expected that Robinson would have made arrangements to get this information to Dev, who was most anxious to meet Collins or Mulcahy at this time’ (ref: Michael Mills former ombudsman).

Collins’s personal diary outlined his plan for peace. Republicans must “accept the People’s Verdict” on the Treaty, but could then “go home without their arms. We don’t ask for any surrender of their principles”. He argued that the Provisional Government was upholding “the people’s rights” and would continue to do so. “We want to avoid any possible unnecessary destruction and loss of life. We do not want to mitigate their weakness by resolute action beyond what is required”. But if Republicans did not accept his terms, “further blood is on their shoulders” (Hopkinson, Green Against Green, the Irish Civil War, pp.177-179)

Emmet Dalton Continues:-“It was now about a quarter past seven and the light was failing. We proceeded along the open road on our way to Macroom. Our Motor Cyclist Scout was a bout 50 yards in front of the Crossley Tender which we followed at the same interval in the touring car, and close behind us came the armoured car.

We had just reached a part of the road that was covered by hills on all sides. The road itself was flat and open; on the right we were flanked by steep hills on the left of the road there was a small 2 ft bank of earth skirting the road. Beyond this there was a marshy field bounded by a small stream and covered by another steep hill. About half way up this hill there was a road running parallel to the one we were on but screened from view by a wall, and a number of trees and bushes.

We had just turned a wide corner on the road when a heavy fusillade of machine gun and rifle fire swept the road in front of us and behind us, shattering the wind-screen of our car.

I shouted to the Driver “Drive like Hell” but the Commander-in Chief placing his hand on his shoulder said “Stop. Jump out, we will fight them.” We jumped from the car and took what cover we could behind the little mud bank on the left side of the road, it appeared the greatest volume of fire was coming from the concealed roadway on our left hand side.The armoured car backed up the road and opened a heavy machine gun fire at the Ambushers. General Collins, I, and another Officer (Joe Dolan) who was near us opened up fire on our seldom visible enemies, with rifles. About fifty or sixty yards further down the road and around a bend we could hear that our machine-gunners and riflemen were heavily engaged. We continued this firefight for about twenty minutes without suffering any casualties, when a lull in the enemy’s fire became noticeable.

General Collins jumped to his feet and walked over behind the armoured car, obviously to obtain a better view of our enemy’s position. He remained there firing occasional shots, using the car as cover. Suddenly I hear him shout “There they are running up the road.” I immediately concentrated on two figures that came in view on the opposite road.

When I next turned round the Commander-in-Chief had left the car position and had run about fifteen yards back up the road, dropped into the prone firing position and opened up on our retreating enemies. A few minutes had elapsed when the Officer in Charge of our escort came running up the road under fire, he dropped into position beside me and said “They have retreated from in front of us and the obstacle is removed; where is the ‘Big Fella’?” I said he is all right – he has gone a few yards up the road, I hear him firing away.”

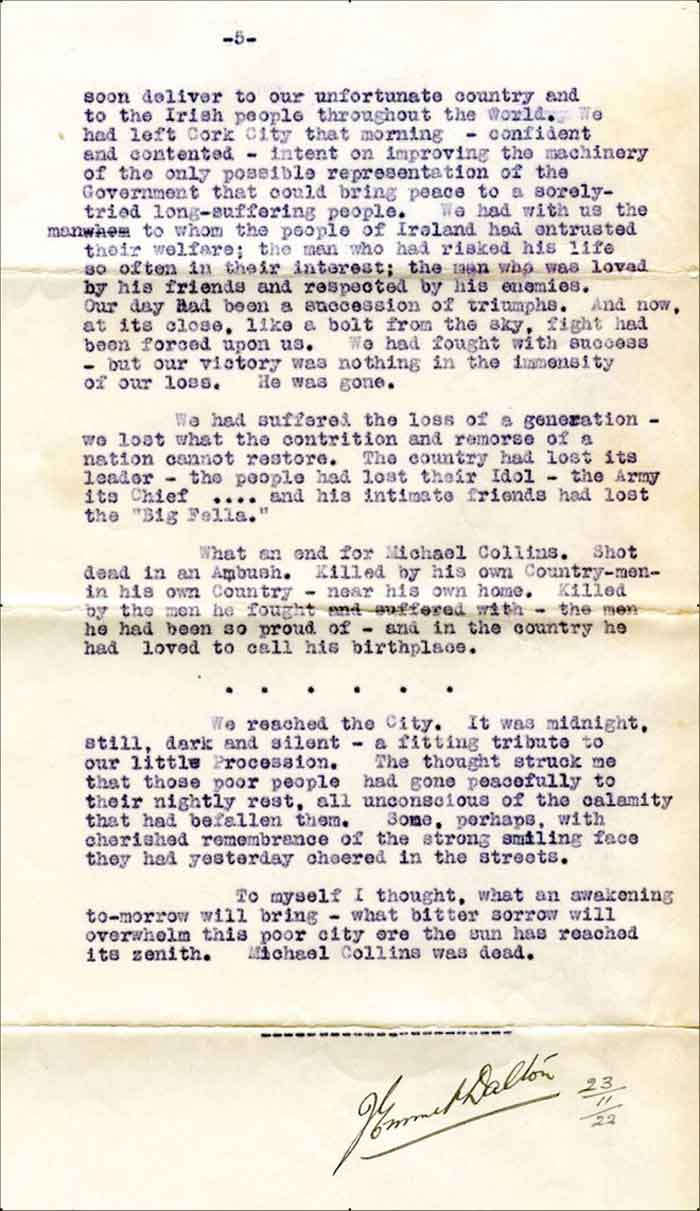

Then I heard a cry “Emmet, I am hit.” The two of us rushed to the spot, fear clutching our hearts. We found our beloved Chief (and friend) lying – motionless in a firing position, firmly gripping his rifle upon which his head was resting. There was a gaping wound at the base of his skull behind his right ear. We immediately saw that he was almost beyond human aid; he did not speak.

The enemy must have observed that something had occured that had caused a cessation in our fire because they intensified theirs. O’Connell knelt beside the dying but conscious Chief, whose eyes were open and normal, and he whispered into his ear the words of the Act of Contrition; he was rewarded by a slight pressure of the hand. Meanwhile I knelt beside them and kept up bursts of rapid fire, which I continued whilst O’Connell dragged the Chief across the road and behind the armoured car.

Free State Soldiers with Hannie Collins at the Ambush site Aug 23rd 1922

Then with my heart torn with sorrow and dispair I ran to his side. I gently raised his head on my knee and tried to bandage his wound, but owing to the size of the wound this proved difficult and I had not completed my sorrowful task when his eyes quietly closed and the cold pallor of death covered his face. How can I describe the feelings that were then mine, kneeling in the mud of a country road not 12 miles from Clonakilty with the still bleeding head of the Idol of Ireland resting in my arms. My heart was broken my mind was numbed, I was unconscious of the bullets which still whistled and ripped the ground beside me. I think that the weight of the blow would have caused me the loss of reason had I not observed the tear-stained face of O’Connell distorted with anguish.

We paused for a moment in silent prayer and then noting that the fire of our enemies had greatly abated and that they had practically all retreated, we two, with the assistance of a third Officer (Lt John J. Smith) who had come on the scene, endeavoured to lift the body on to the back of the armoured car. It was then that we suffered our second casualty, the recently arrived Officer being shot in the neck. He, however, remained on his feet and helped us to carry our precious burden around a turn in the road under the cover of the armoured car.

Having transferred the body of our Chief to the armoured car where I sat with his head resting on my shoulder, our sorrowful little party set out for Cork. The darkness of night had closed over us like a shroud. We were silent, thinking with heavy hearts of the terrible blow we would soon deliver to our unfortunate country and to the Irish people throughout the world. We had left Cork City that morning – confident and contented – intent on improving the machinery of the only possible representation of the Government that could bring peace to a sorely-tried long-suffering people.

We had with us the man to whom the people of Ireland had entrusted their welfare; the man who had risked his life so often in their interest; the man who was loved by his friends and respected by his enemies. Our day had been a succession of triumphs. And now, at its close, like a bolt from the sky, fight had been forced upon us. We had fought with success but our victory was nothing in the immensity of our loss. He was gone.

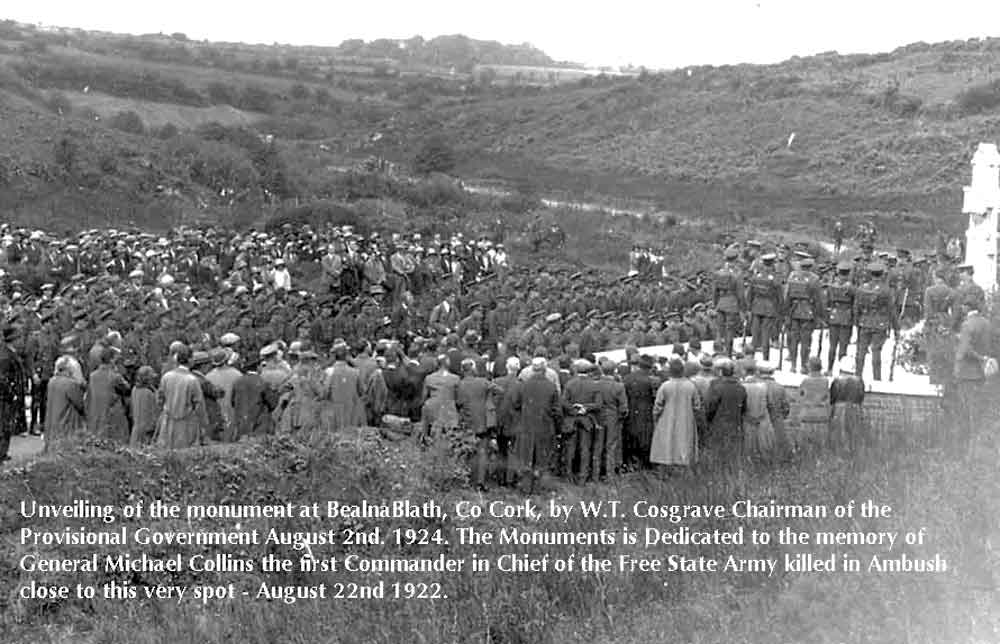

What an end for Michael Collins, Shot dead in an Ambush. Killed by his own Countrymen in his own Country – near his own home. Killed by the men he fought and suffered with –the men he had been so proud of –and in the country he had loved to call his birthplace.

We reached the City. It was midnight, still, dark and silent – a fitting tribute to our little Procession. The thought struck me that those poor people had gone peacefully their nightly rest, all unconscious of the calamity that had befallen them. Some, perhaps, with cherished remembrance of the strong smiling face they had yesterday cheered in the streets.

To myself I thought, what an awakening tomorrow will bring – what bitter sorrow will overwhelm this poor city ere the sun has reached its zenith. Michael Collins was dead.

[signed] J Emmet Dalton, 23/11/22″ END

Due to damaged bridges the Convoy Party had to cross fields to get to the main road for Cork City, This proved to be very difficult. The Leyland Touring car got bogged down when traversing the fields near Kilumney village and had to be abandoned. The Convoy continued with just the two vehicles the Crossley Tender and the Slievenamon armoured Car – The Slievenamon too had to be abandoned failing to traverse the soft earth – The Crossley tender conveyed the body of the dead Chief to Shanakiel Hospital. The following day the leyland tourer and Armoured car was recovered by Army personnel. The Clock which was stopped at 7.32 pm had been taken from the Touring Car’s dashboard. In the 1990’s the clock was handed in to the Army at Collins Barracks Cork by the family who had possession of it since 1922. (Source family grand-daughter 2013 (Bill Martin))

RETURN TO INDEX

REFERENCES

(1) – August 21st 1922 – ‘Briar of Life’ Biography by A.J.S (Stephen) Brady 2010 Chapter 18 – published after his death by family from his transcripts.

(2) The Ambush

(3) The Tipperary Connection – John Hourihan Historian

(4) Colm Connolly “Shadow of BealnaBlath”

(5) Michael Mills Politico,ie – THURSDAY, 01 JANUARY 1. 1998.

(6) Treaty Negotiations

(7) Truce & Correspondance

(8) The Irish State by Dr. Garret Fitzgerald