The Irish Press Story

The Irish Press Story

“A Ruler should, as far as possible, observe conventional standards of morality, but providing he gives the appearance of doing so, he can act in a dishonest and ruthless fashion when it suits his interests”. [Niccolo Machiavelli. ‘The Prince’]

Between the 3rd and the 12th of May 1916, fifteen of the leaders of the Easter Rising, including the signatories of the Proclamation of the Republic, were shot to death by the British at Kilmainham Jail, Dublin. They were Eamonn Ceannt,* Thomas James Clarke,* Con Colbert, James Connolly,* Edward Daly, Sean Heuston, Thomas Kent, John MacBride, Sean MacDiarmada, *Thomas McDonagh,* Michael Mallin, Michael O’Hanrahan, Patrick Pearse,* William Pearse and Joseph Mary Plunkett.* James Connolly, badly wounded in the fighting, had to be stretchered to the yard and he was propped up in and tied to a wooden chair borrowed from the kitchen to face the firing squad; it was May 12th and he was the last victim. In time those rifle shots would be recognised as having sounded the death-knell of the British Empire. US born secondary school teacher, Eamonn de Valera, Commander of the 3rd Dublin Volunteer Battalion, escaped when public opinion forced Prime Minister Asquith to order an end to the killings and his death sentence was commuted to 15 years penal servitude. Roger Casement would be hanged in Pentonville Gaol, London on August 3rd, the only leader of the Rising to be executed outside Ireland. [ * indicates the seven signatories ]

Between the 3rd and the 12th of May 1916, fifteen of the leaders of the Easter Rising, including the signatories of the Proclamation of the Republic, were shot to death by the British at Kilmainham Jail, Dublin. They were Eamonn Ceannt,* Thomas James Clarke,* Con Colbert, James Connolly,* Edward Daly, Sean Heuston, Thomas Kent, John MacBride, Sean MacDiarmada, *Thomas McDonagh,* Michael Mallin, Michael O’Hanrahan, Patrick Pearse,* William Pearse and Joseph Mary Plunkett.* James Connolly, badly wounded in the fighting, had to be stretchered to the yard and he was propped up in and tied to a wooden chair borrowed from the kitchen to face the firing squad; it was May 12th and he was the last victim. In time those rifle shots would be recognised as having sounded the death-knell of the British Empire. US born secondary school teacher, Eamonn de Valera, Commander of the 3rd Dublin Volunteer Battalion, escaped when public opinion forced Prime Minister Asquith to order an end to the killings and his death sentence was commuted to 15 years penal servitude. Roger Casement would be hanged in Pentonville Gaol, London on August 3rd, the only leader of the Rising to be executed outside Ireland. [ * indicates the seven signatories ]

At Christmas 1916, chiefly in a PR exercise to appease Irish American interests, Volunteer prisoners, including one Michael Collins, were released from Frongoch POW Camp in Wales and Arthur Griffith was released from Reading Jail. The Irish National Aid and Volunteer Dependants Fund had been founded in May 1916 to help those families who suffered from their participation in the Rising; it was funded mainly from the US and Joseph McGrath, later of rish Hospital Sweepstake fame, was the first secretary manager. On Feb 16th, 1917, on McGrath’s resignation, Michael Collins took over the high profile job and quickly showed his talent for organisation and efficiency.

The work kept him in touch with the rebel world and he quickly became known as the man to see, the man to get things done and this gave him status as an insider in the Post-Rising separatist movement. He held the job for 18 months and the contacts and networks established then would stand him in good stead during what was to come. On June 1,5lh 1917 it was announced that all 1916 prisoners were to be released under amnesty and on June 18th Eamonn de Valera arrived back in Dublin on board the SS Munster. On May 17th 1918 he was re-arrested for conspiracy along with other activists and sent to Lincoln Gaol.

In the general election of 1918, in which women [over 30 years old] were allowed to vote for first time, de Valera, Collins and 71 other Sinn Fein candidates were elected, although 34 of them were in jail in England and another 6 on the run. On January 21st 1919 the first sitting of Dail Eireann, comprised of those MPs still at large, took place in The Mansion House, Dublin, and the 1916 Declaration of Independence was formally and unamanimously ratified. Despite being branded as a dangerous and illegal organisation and it’s members instantly hunted, and despite having to meet in secret, this 1st Dail was to last until May 1921 and set up what was in effect a Parallel Government with its own Ministries, Courts and Police.

At the Dail’s second meeting, on April 1st, 1919, this time with a full complement of members, Eamonn de Valera was elected Priomh Aire [First Minister] and formed his first Cabinet with Michael Collins as Minister of Finance. De Valera had been sprung from lincoln by Michael Collins and an IRB squad on February 3rd. He had made an imprint of the master-key of the prison on candle wax obtained while serving Mass and drawings of the key and details of it’s dimensions were smuggled out of the prison in an attempt to have duplicate keys made.

The first two copies failed to work and finally one of the other Sinn Fein prisoners, Peter de Loughry, of the de Loughry Foundry, New Building Lane, Kilkenny, asked for a blank key and some files to be obtained from his family firm; this was done and these were then baked into loaves of bread at Crotty’s Bakery, Parliament Street, Kilkenny and smuggled back to the prison. Being an expert locksmith, Peter then made the key which opened all the doors and allowed de Valera, Sean Milroy and Sean McGarry to gain their freedom. The adventure greatly enhanced de Valera’s reputation. The key which was to be seen on display at Rothe House, Kilkenny is now in the National Museum, in Dublin.

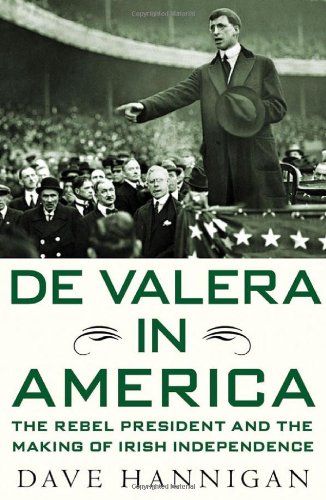

De Valera then shocked and dismayed his comrades by announcing that, instead of returning to the war in Ireland, he had decided to travel to America, where he would work to raise awareness of the struggle for Independence and seek support and money for The Cause. Despite the urgent entreaties of his comrades to stay, he was not for turning. It would later be put about in a face saving exercise, that he had been persuaded and encouraged to go; nothing could be further from the truth. The heaviest fighting and the most brutal, terrible and decisive events of the War would take place during his absence. De Valera was smuggled aboard the SS Lapland at Liverpool as a seaman and arrived in New York on June 11th, 1919. One of the first staff appointments he made was that of a Kerry woman, Kathleen O’Connell, as his secretary, a post she would hold until her death in 1956. He was to remain in the US for 18 months and during this time Michael Collins, the most wanted man in Ireland, would cycle to deValera’s home in Greystones, Co. Wicklow nearly every week to provide his wife, Sinead, with the money to support their young family and to keep them together.

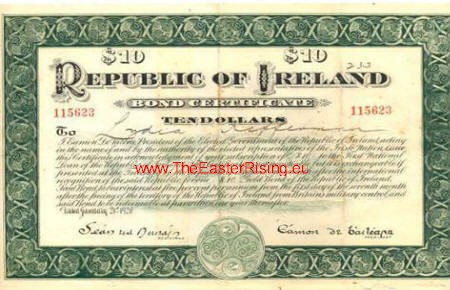

The North American tour, initially stage managed by Harry Boland and later organised and choreographed in the main by Galway man Liam Mellows, proved a great success financially with huge crowds greeting him as a hero wherever he appeared. He was welcomed and feted by Mayors and Governors and granted the Freedom of Cities and States. He became the self styled, ‘President of the Republic of Ireland’, and brought “Greetings to the Sons and Daughters of the Gael from the Motherland “. To raise funds he had elaborate Bond Certificates printed and issued for sale with the promise that they would be redeemed with interest when The Irish Republicwas established. Support came in the main from the working class Irish Americans; domestics, bartenders, labourers, cops and other low earners, who believed that they were doing their patriotic duty and helping to ‘Free their Native Land’.

In all de Valera collected between five and six million dollars, a huge sum at the time, but sent less than half back to Ireland, although at that time “men were dying for the lack of the few rounds of ammunition to defend themselves”. ‘He left over three million dollars, approx 6o% of the total, in banks in the US for reasons which would only become clear in time’. De Valera had always cultivated an image of austerity, integrity and frugality but during his time in the US he lived in the luxurious Waldorf Astoria Hotel while in New York City, and in similar up-market establishments during his travels over and back across the continent. He also kept open house hospitality, entertaining and providing refreshment for all comers and was never seen to be short of money. He made the contacts then that would greatly assist him in carrying out his future plans; the most important of these contacts was one Matthew Garth Healy, a lawyer, and a man very involved with all the major Irish organisations in the US. Healy was to become de Valera’s right hand man in his business transactions in America.

“When he returned home to Dublin, de Valera left the proud Irish-American organisations that had welcomed, supported and financed him split irrevocably; and he had failed to achieve his primary objective ie. to have the newly declared Republic of Ireland recognised by the US Government of President Woodrow Wilson.

On December 13th 1920 de Valera was smuggled on board SS Celtic bound for Liverpool and arrived back in Dublin on the 23rd of the month where he was met at the docks by IRB men Tom Cullen and Batt O’Connor. When he asked how things were going, Cullen told him “Great. The Big Fellow is leading us and everything is going marvellous”. De Valera replied “Big Fellow? We’ll see who is the Big Fellow”. He soon found that Michael Collins, with his unique organising ability, had become the ‘main man’, running everything in sight, including the IRB. He immediately tried to send him to the US ‘to carry on publicity work’ but Collins would not hear of it, telling friends that “The Long ‘Hoor” wont get rid of me that easily”. Collins, generally acknowledged as the architect of modern Hit and Run Guerrilla Warfare, had created a countrywide network of agents with contacts inside all government departments, including Dublin Castle itself.

On December 13th 1920 de Valera was smuggled on board SS Celtic bound for Liverpool and arrived back in Dublin on the 23rd of the month where he was met at the docks by IRB men Tom Cullen and Batt O’Connor. When he asked how things were going, Cullen told him “Great. The Big Fellow is leading us and everything is going marvellous”. De Valera replied “Big Fellow? We’ll see who is the Big Fellow”. He soon found that Michael Collins, with his unique organising ability, had become the ‘main man’, running everything in sight, including the IRB. He immediately tried to send him to the US ‘to carry on publicity work’ but Collins would not hear of it, telling friends that “The Long ‘Hoor” wont get rid of me that easily”. Collins, generally acknowledged as the architect of modern Hit and Run Guerrilla Warfare, had created a countrywide network of agents with contacts inside all government departments, including Dublin Castle itself.

He had recognised the need for an active intelligence and communications unit in 1916 while interned in Frongoch, [situated at an abandoned distillery in North Wales] where he met and befriended Volunteers from all over Ireland: Frongoch came to be dubbed The University of Revolution. Three years later a number of those men, under Dick McKee, Commander of the Dublin Brigade, were to become the nucleus of a team, known as the Special Duty Squad, formed to carry out specific assignments, including assassinations. They would be armed initially with .38 revolvers, until ·45 were found to be more effective, and their main targets would be members of Dublin Castle’s ‘G’ Division, the mainstay of the British Intelligence system in Ireland, and the so called ‘Igoe Gang’, policemen drafted into Dublin from around the country to identify and j or assassinate prominent Sinn Fein members. It was in Frongoch that Volunteers first began to refer to themselves as The Irish Republican Army. The Squad began operations in mid 1919, and by March 1920, all members had been put on a paid full-time basis. Up to then the IRA were mostly part timers, as they all had to earn their livings, and operations were carried out either at night or at week-ends. Initially, twelve men, all young and unmarried, quit their jobs and were inducted; They were immediately dubbed ‘The Twelve Apostles’. The original12 were, Ben Barrett, Eddie Byrne, Vinnie Byrne, Jimmy Conroy, Sean Doyle, Paddy Griffin, Tom Keogh, Joe Leonard, Mick McDonnell, Paddy [0′] Daly, Mick O’Reilly, and Jim Slattery while Pat McCrea acted as their driver. Michael Collins was Director of Intelligence and Liam Tobin Deputy Director; Tom Cullen and Frank Thornton were appointed Assistant Director and Deputy Assistant Director. An Intelligence Office was established a stone’s throw from Dublin Castle at 3 Crow Street, just off Dame Street, while the Squad’s first of many H/ Qs was a private house at 100, Seville Place, Dublin.

The violence began on January 21st, 1919, the same day the first Dail was set up, when, without authorisation from H/Q, a party of Volunteers, [Tim Crowe, Sean Hogan, Patrick McCormack, Patrick O’Dwyer, Jack O’Meara, Seamus Robinson, Michael Ryan] led by Dan Breen and Sean Treacy, shot dead 2 catholic policemen, James McDonnell, a widower with a young family, from Belmullet, Co. Mayo, and, Patrick O’Connell, from Glenmoyie, Coachford, Co. Cork, while seizing a consignment of gelignite at Soloheadbeg, Co. Tipperary. The gunmen had decided that the movement needed a push and the two policemen became the first hapless victims of the War of Independence.

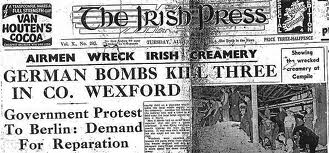

But it was 1920 that became known as The Year of Terror with the arrival of the Black and Tans [named after the hounds of the Scarteen Hunt, Co. Tipperary] and the Auxiliaries. It was estimated that over two hundred unarmed civilians, including women and children, were killed by Crown forces in that year. The centre of Cork city was burned to the ground, as well as creameries, bacon factories and mills all over the country; leading Nationalists were identified and murdered; on March 20’\ Tomas MacCurtain, Lord Mayor of Cork, was shot to death at his home; towns were sacked, civilians indiscriminately shot and scores of houses and business buildings burned. Eighteen-year-old student, Kevin Barry, became the first rebel to be officially executed since 1916 when he was hanged on All Souls’ Day, November 1st, a day after the funeral of Terence MacSvviney, MacCurtain’s successor as Lord Mayor of Cork; he had died on hunger strike in Brixton Prison on October 25th while fellow Volunteers, Michael Fitzgerald and Joseph Murphy, died on hunger strike in Cork Prison the same month.

Between November 1920 and June 1921 nine other Volunteers were hanged and buried in Mountjoy Prison. They were; Thomas Bryan, Patrick Doyle, Frank Flood, Edmond Foley, Patrick Maher, Patrick Moran, Bernard Ryan, Thomas Traynor and Thomas Whelan. Father Michael Griffin, a young priest of Galway city, who was due to be interviewed on the crisis by The Nation, an American current affairs publication, was called out on a bogus sick-call at midnight on Sunday, November 14’h and his body found a week later with a bullet in his temple. He was the first priest to be murdered in Ireland since the dark days of Oliver Cromwell. On the other hand the IRA raided and burned dozens of RIC and Police Barracks, Courthouses and loyalists’ homes and large-scale ambushes were the order of the day. Spies and informers were identified and executed out of hand. On November, 28th 1920 former British soldier, Tom Barry, and the West Cork Flying Column ambushed and wiped out an Auxiliary patrol of 17 men at Kilmichael, County Cork. Seven days earlier, at nine o’clock on the morning of Sunday November 21st, at up to a dozen different addresses around Dublin, the Squad, assisted by a number of Dublin Brigade members, including one Sean Lemass, shot dead at least 14 British officers, most of them members of the so called ‘Cairo Gang’, the newly arrived elite of the British intelligence service; later that day Black and Tans and Auxiliaries showed up at a football match between Dublin and Tipperary in Croke Park and shot indiscriminately into the crowd killing 12 civilians and wounding many more. Michael Hogan, full-back on the Tipperary team died and is remembered with the Hogan Stand. The day vvas to go down in history as Bloody Sunday.

Between November 1920 and June 1921 nine other Volunteers were hanged and buried in Mountjoy Prison. They were; Thomas Bryan, Patrick Doyle, Frank Flood, Edmond Foley, Patrick Maher, Patrick Moran, Bernard Ryan, Thomas Traynor and Thomas Whelan. Father Michael Griffin, a young priest of Galway city, who was due to be interviewed on the crisis by The Nation, an American current affairs publication, was called out on a bogus sick-call at midnight on Sunday, November 14’h and his body found a week later with a bullet in his temple. He was the first priest to be murdered in Ireland since the dark days of Oliver Cromwell. On the other hand the IRA raided and burned dozens of RIC and Police Barracks, Courthouses and loyalists’ homes and large-scale ambushes were the order of the day. Spies and informers were identified and executed out of hand. On November, 28th 1920 former British soldier, Tom Barry, and the West Cork Flying Column ambushed and wiped out an Auxiliary patrol of 17 men at Kilmichael, County Cork. Seven days earlier, at nine o’clock on the morning of Sunday November 21st, at up to a dozen different addresses around Dublin, the Squad, assisted by a number of Dublin Brigade members, including one Sean Lemass, shot dead at least 14 British officers, most of them members of the so called ‘Cairo Gang’, the newly arrived elite of the British intelligence service; later that day Black and Tans and Auxiliaries showed up at a football match between Dublin and Tipperary in Croke Park and shot indiscriminately into the crowd killing 12 civilians and wounding many more. Michael Hogan, full-back on the Tipperary team died and is remembered with the Hogan Stand. The day vvas to go down in history as Bloody Sunday.

The violence continued unabated into 1921; de Valera, who had always favoured ‘static warfare’, demanded a ‘spectacular operation’ and on 25th May, against the wishes and advice of Collins, a force of approximately 120 Volunteers, led by Tom Ennis, surrounded and entered the Custom House in Dublin, the centre of British Administration in Ireland, and set it on tire, destroying the building and it’s priceless governmental records; but 6 volunteers were killed, 12 wounded and approx 8o captured. It was the greatest operational disaster of the war, with the loss of so many of their best men and their weapons a severe blow to Collins and the IR.A and it effectively led to the disbanding of The Squad; but it was the largest single action in Dublin since the Easter Rebellion and achieved world wide media coverage. It became clear that the situation could not be allowed to continue and under mounting pressure from public opinion at home and in the US, Lloyd George sent word that he wanted peace and in July, 1921, a temporary truce was agreed, ” to ex-plore to the utmost the possibility of a settlement to end the ruinous conflict of centuries. Michael Collins, the ex Post Office clerk, and his comrades in the IR.A had forced The British Empire, on which the sun never set, to the negotiation table, an historic achievement in itself .

It is an interesting though pathetic fact that between ,July and the end of 1921 the rank.s of theIRA swelled from about 3000 active members to approx 70,000; the fighting was seen as being over and the Truce-ileers had arrived. The scramble for pensions, medals, jobs and whatever other ‘goodies’ might come on offer had begun; the ‘Gombeen’ men had made their entrance and many would say that they are still in charge.

The Truce began at noon July11, 1921 and on July 12th, a symbolic day, de Valera travelled to London with a hand picked delegation, which did not include Michael Collins. His team, which included Arthur Griffith, Austin Stack, Robert Barton, Erskine Childers and George Noble Plunkett, was booked into the Grosvenor Hotel while he himself stayed at 5, W.Halkin Street with his friends, the Farnans, and Kathleen O’Connell, his secretary. He left his colleagues at the hotel and had four private, one to one, meetings with Lloyd George at Downing Street between July 14th and July 21st and terms and conditions for Treaty negotiations were at length worked out and agreed.

Coming away from those meetings de Valera alone knew with absolute certainty that a Republic was out of the question, and that whoever went to negotiate a Treaty would inevitably have to accept a compromise. But the fact is that de Valera himself, by accepting the invitation to the conference under those conditions, had, in effect, already made the compromise and given up the Republic, while also, ‘de facto’, recognising Partition.

However, he was not going to reveal himself as the one who had sacrificed The Holy Grail; that was not a part of his plan; a scapegoat was needed and he had just the man in mind.

The Treaty talks commenced on October nth, 1921, and Eamonn de Valera showed his colours by refusing, not alone to lead the team, but to be a part of it, insisting that Collins, despite his total lack of negotiating experience, travel in his stead. Collins objected strongly but in the end, not being a man to shirk what he saw as his duty to his country, agreed to travel. Meanwhile the man who had decided his place was in America during most of the Black and Tan war now decided he should stay in Dublin during the coming diplomatic ‘war’ in London; the captain of the ship in a storm was going to plot it’s perilous course from the safety of dry land; de Valera was going to stay at home and play politics.

England put out its strongest and most experienced delegation, which included Prime Minister David Lloyd George, Lord Birkenhead, Austen Chamberlain and Winston Churchill. The Irish team was, Arthur Griffith,

Michael Collins, Robert Barton, Eamonn Duggan, and George Gavin Duffy; Erskine Childers was named principal Secretary with back-up from John Chartres, Diarmuid O’Hegarty and Fionan Lynch. Collins and some of his close associates stayed at 15, Cadogan Gardens, London while Griffiths and the others moved into 22, Hans Place, London. De Valera would later write that he had deiiberateiy built divisions into the delegation, a claim which was borne out when, to their everlasting shame, two of the team, Gavin Duffy and Barton, later reneged and opposed the Treaty they themselves had helped to negotiate and to which they had signed their names. Erskine Childers, Barton’s cousin, would also allow himself to be swayed by de Valera and pay for it with his life.

The team was given full plenipotentiary powers to treat with the British and, at last, after much to-ing and froing to Dublin for co:nsultations, during “Which de Valera refused repeated requests to join the talks, and under threat of” immediate and terrible war”, at 2.3oam, on Tuesday, December 6th, 1921, The Anglo Irish Treaty was signed. Michael Collins, ever the pragmatist, wrote to a friend: “Think what have I got for Ireland? Something she has wanted these past 700 years. Will anyone be satisfied at the bargain? Will they I tell you this-early this morning I signed my death warrant. I thought at the time how odd, how ridiculous – a bullet may just as well have done the job 5 years ago. These signatures are the first real step for Ireland . If people will only remember that-the first real step.”

For Collins knew the strengths and, more importantly, the weaknesses of the IRA down to the last bullet and he knew they could no longer hope to defeat the British militarily as, with the Truce, they had lost their greatest weapon, Anonymity; he and all his agents and associates were now known and identifiable, and could be easily exterminated if the talks failed; so a deal was essential at that time. Collins saw it as a stepping-stone to a 32county Republic; it gave Ireland “the freedom to achieve freedom”, a forecast which time would prove to be accurate. It is reckoned that at the time there were fewer than 3000 poorly armed active Volunteers as against 5o,ooo British soldiers, thousands of loyal police plus the Auxies and Tans.

The Treaty, effectively de Valera’s Treaty, was brought back to Dublin, debated at length, and on January 7th, 1922 voted on and passed by Dail Eireann; it was subsequently democratically endorsed by the people of Ireland in a General Election on June I 6th when de Valera and his followers won just 36 seats out of a total of 128. It was the very first time that the Proportional Representation system was used in a General Election. In England, Churchill and Birkenhead shepherded the Treaty through the Commons and House of Lords respectively, against a raging storm of Tory and Unionist opposition. Ireland, after 700 merciless years of slavery and injustice, could finally look forward to Freedom, practical Independence and Peace. The handover of power took place on January 16th 1922 when the keys of Dublin Castle were handed over to Michael Collins and a miracle had been performed; after all the lost opportunities Home Rule and Self Determination were at last a reality.

There followed the most monstrous betrayal in our country’s history. Eamonn de Valera betrayed the men he sent to make the peace, and rejected the democratic voices of both the Dail and the People. Instead of doing his duty for Ireland and showing loyalty, courage and leadership by rallying support and throwing his authority behind the Treaty, his Treaty, to maintain national unity and solidarity, he rejected it and deliberately set out to attract and foment extremist support for his actions. ‘The Majority have no right to do wrong’. By so doing he created the precedent and the template for the future ‘Provisional IRA’, the ‘Real IRA’, ‘the Continuity IRA’ and any other radical ‘Republican’ splinter groups which down to the present day follow his lead and ‘continue the struggle’. De Valera introduced The Split into Irish politics.

He organised rallies across the country speaking out against the Treaty, ranting on about ” men marching over the dead bodies of their own brothers” and “wading through Irish blood”. Under his malign influence the fanatics, the zealots, the deluded, and the misguided people who followed him became, in effect, renegades and enemies of the people and set out to destroy the fledgling State which had been so hard won through centuries of sacrifice, blood, sweat and tears. Revolutionary Leaders turned Peace Makers might expect attacks from ambitious foot soldiers, wild men who wished to continue the violence for their own, often criminal, purposes, but, surely, not to be stabbed in the back by one of their ow11 and especially by one held in such high esteem.

Eamonn de Valera sowed and fertilised the poisoned seeds of the terrible, obscene and destructive civil war which followed and, although it lasted barely 13 months, due to lack of support or sympathy from the people for him and his ‘irregulars’, it created bitterness, divisions and hatred between friends and families, which have lasted down to this very day. He robbed the people of their joy in a great victory when there was no need or justfication for a shot to be fired, and it should be noted that he himself stayed well away from the scenes of voilence, to look after the ‘political’ end of things; he still had his personal dislike of’shooting guns.

This was the bleakest period of Irish history; the IRA Freedom Fighters, men who had, side by side, faced the of the British Crown Forces in the age old stand against oppression, the struggle for liberty, were brainwashed into turning their guns against each other with tragic results. The damage de Valera did to Ireland is incalculable; a crack team of British agents and saboteurs could not have done a more effective job; it was a time of anarchy, criminality and incredible savagery, and how London must have enjoyed the spectacle: their belief that the Irish were incapable of looking after their own affairs had been most emphatically confirmed.

This was the bleakest period of Irish history; the IRA Freedom Fighters, men who had, side by side, faced the of the British Crown Forces in the age old stand against oppression, the struggle for liberty, were brainwashed into turning their guns against each other with tragic results. The damage de Valera did to Ireland is incalculable; a crack team of British agents and saboteurs could not have done a more effective job; it was a time of anarchy, criminality and incredible savagery, and how London must have enjoyed the spectacle: their belief that the Irish were incapable of looking after their own affairs had been most emphatically confirmed.

But why did he do it? Journalist and historian, the late Con Houlihan, reckons that at that time deValera was clinically insane. But is that not being too magnanimous? When one considers what is now known of his subsequent very sane, calculated and self-serving financial wheeling and dealing I believe it is entirely far too charitable.

Nothing he ever said or did subsequently could redeem his honour or begin to explain, justify or make amends for his treachery at that terrible time. Finally, on May 24th, 1923, de Valera and his followers surrendered and the war ended but not before the conflict had ripped open the fabric of Irish society. It had brought about the violent deaths of upwards of 2000 Irish citizens, including his friend, comrade, main rival for leadership and greatest Republican of them all, Michael Collins, who was shot dead by one Denis ‘Sonny’ O’Neill, an ex-British Army marksman, during an ambush at Beal-na-mBlath, County Cork, on August 22nd 1922; and it is more than likely that the gun that killed him was sourced and supplied by Collins himself. Earlier in that black month Michael’s former great friend and comrade, Harry Boland, had died a few days after being shot in action in Skerries, Co. Dublin, on July 31st and Arthur Griffiths, ‘the poorest man in Ireland’, died of a brain hemorrhage on August 12th. aged 51.

In 1922, the democratically elected Irish Government of William T. Cosgrave sought to bring home the sorely needed Bond money which remained in the US, but de Valera opposed the move and disputed the ownership of the American funds. After a protracted, expensive and wasteful law case, in 1927 the New York Supreme Court decreed that the funds be returned to the original Bondholders. The ‘independent’ person entrusted with the task of organising the repayments was one Matthew Garth Healy and de Valera had gained access to the names and addresses of the investors.

In 1922, the democratically elected Irish Government of William T. Cosgrave sought to bring home the sorely needed Bond money which remained in the US, but de Valera opposed the move and disputed the ownership of the American funds. After a protracted, expensive and wasteful law case, in 1927 the New York Supreme Court decreed that the funds be returned to the original Bondholders. The ‘independent’ person entrusted with the task of organising the repayments was one Matthew Garth Healy and de Valera had gained access to the names and addresses of the investors.

He wrote a series of letters to each of the bondholders appealing to them, for the benefit of Ireland, not to cash their cheques but to assign their bonds to him personally to help finance the setting up of an Irish National Newspaper “to counter lying propaganda and to break the saanglehold of the alien press in Ireland”. His letters evoked a huge response from the loyal and patriotic bondholders who still believed that they were supporting “The Cause”. They gave de Valera, in effect, a blank cheque, which he then used to bank a very large sum of money in his own name, and none of the funds initially subscribed to help ‘Set Old Ireland Free’ came back to help the Motherland.

In 1926, Eamonn de Valera, or George de Valero, as The State of New York birth certificate, registered on 10 November 1882, describes him, founded a new political party to be called Fianna Fail and in 1928 floated a company to establish an ‘independent ‘Republican’ Newspaper for the people’. Thousands flocked to invest, this again being “The Cause”, but, to the puzzlement of the people, he would allow Irish investors subscribe only half of the Capital, insisting that 50% must come from the US.

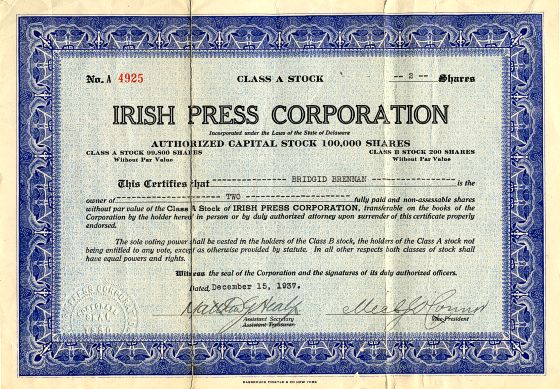

In 1928 he sent two veterans of the war for independence, Frank Aiken and Ernie 0’Malley, to America to raise the funds, this time presenting the proposition as a viable investment, vvith a return of 15% being touted, and spent a lot of time there hlmself to drum up support. But, again, al! was not as it seemed. deValera had set-up a Trust Company, Irish Press Corporation, registered in Delaware, the “Cayman Islands” of the time, and American investors were given “Certificates of Participation” in this rather than the shares in The Irish Press Limited which they had paid for.

These certificates were designated as “Class A” shares; but de Valera had set up the company to be controlled by the holder of 200 ‘B’ shares, which he then quietly purchased in his own name with $1000 of the investors’ money. He had, by sleight of hand, taken control of more than $250,000 at absolutely no cost to himself. Anticipating problems with some of the less innocent and more business minded investors, he made provision for anyone of influence who made a big enough fuss, to be supplied with shares in the Irish company, and he himself saw to it that personal friends and associates were looked after from the £5,000 worth of shares he had set aside for this purpose. Then, using $1000 of the Corporation’s funds, he bought 43% of the Irish company in his ovvn name. deValera had, in effect, bought The Irish Press with other people’s money. It was a carefully planned, cunning and devious swindle of monumental proportions; and he got away with it. White collar crime had arrived.

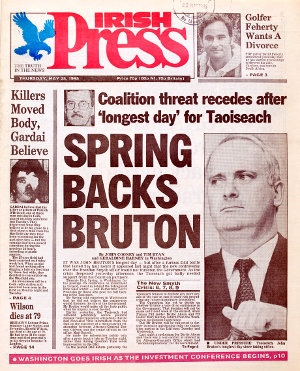

The Irish Press Limited, the so-called ‘Republican’ paper, was launched on September 5th 1931, vvith Padraic Pearse’s mother being brought in to perform the ceremony. The slogan was “The Truth in the News” and for the very first time reports of events such as GAA games were available to the public; and they loved it. ” The IRA Courier Service” saw to it that the paper was available everywhere, even being distributed at Masses, and Fianna

Fail took full advantage. After the General Election in 1932 the party was able to form a government for the first time and The Irish Press, de Valera’s daily mouthpiece for the Gospel of Fianna Fail and Cult of de Valera had played a huge part in the victory; as had massive personation of the dead, the sick and the emigrated. ‘The Chiefs’ control of what was then The Media had delivered the power he had always craved and, significantly, it had not cost him one penny. From then on gaining and holding on to power by any means whatsoever became, and down to the present day remains, Fianna Fail’s very successful Number One Policy.

During the global recession of the early 1930s The Irish Press was in financial difficulties and de Valera turned to the money in the US for salvation. He introduced a Bill in the Dail to repay the American Bondholders, calling

it a ‘debt of honour’, and a very acrimonious debate ensued in Dail Eireann. However, in July 1933 he forced the Bill through and approximately £I,500,000, which included a premium of 25%, was paid out of public coffers at a time of grinding poverty and hardship in Ireland. Of course, what the people were not aware of then was that a substantial sum of that money went straight to de Valera himself as the owner of the thousands of Bonds which had been assigned to him for ” The Cause “. It is not known just how much of the money he pocketed but he was able to clear the Paper’s debts and, in addition, purchase 35,000 more shares in the names of himself and his son, Vivian. By not allowing the shares to be quoted on the Irish Stock Exchange, de Valera concealed their true commercial worth, and was then able to buy them from the naive and trusting minority shareholders at knock down prices.

During the 1930s, 40s and sos, the so-called ‘de Valera years’, Ireland was a land of Stagnation, Deprivation and Emigration; of Poverty, Unemployment and TB; of Clericalism, Industrial Schools and Orphanages; of Censorship, Cronyism and Nepotism; with the worst slums, the highest infant mortality rate and the lowest living standards in Northern Europe; and the population had dropped to just 2.8 million by 1961. Between 1951 and 1961 alone, 400,000 people, mostly young men and women, emigrated from Ireiand; almost a 6th ofthe entire population.

But de Valera prospered, with his Irish Press introducing a Sunday edition in 1949, which, in time, would sell 400,000 copies a week, and an Evening Press in 1954. In the 1950s it was one of the most successful and profitable businesses in the country, but his fabled meaness was manifesting itself. The staff were the worst paid of any newspaper, with wages and conditions which were described as appalling, and the atmosphere one of desolation, doom, suspicion and intrigue’; and none of the promised dividends had yet been paid.

So where was all that money going? In the late 1950s TDs, Jack McQuillan and Noel Brown, who had been given a present of one share in the paper and was thus entitled to consult it’s records, began to investigate de Valera’s involvement with The Irish Press and discovered some very interesting facts. Eamonn de Valera himself was now the major shareholder and in 1928, when he was setting up the paper, he had quietly given himself the unusual title of Controlling Director, taking to himself the sole and absolute power over all aspects of the business, and arranging it so that he could not be removed from that position. In 1932, when he formed his first government, to avoid accusations of “conflicts of interest”, he had insisted that all members of the cabinet give up any company directorships they might hold, and de Valera himself resigned as Chairman of The Irish Press Lid; but he kept quiet about his shadowy and much more important Controlling Director role.

On December 12th, 1958 he was challenged in the Dail by Noel Brown, and he maintained that his interest in the paper was purely ‘fiduciary, a sacred moral trusteeship’ to look after the interests of the shareholders, and that he had never received payment for anything he had ever done for the paper; there was no conflict of interest. This was a clear and blatant untruth, a so-called de Valera fact, and he was uncomfortable under questioning in the Dail. In January 1959, at 77 years of age, the party persuaded him to step down as Taoiseach and declare his intention to run for President. It is recorded that he found it extremely hard to relinquish the levers of power but his sudden departure diverted attention from his relationship with the newspaper and the true and scandalous facts did not enter the public consciousness.

With de Valera installed in the park, it was assumed by the membership of Fianna Fail that control of the ‘Republican’ Paper would now pass to a senior member, such as Sean Lemass, who had replaced de Valera as Taoiseach, and stay in the party where it belonged; but they were in for a rude awakening. Two years earlier de Valera had given himself the sole right to nominate his successor and had named his son, Vivion, as the new Controlling Director. He had also brought Vivion’s brother-in-law and long-time de Valera insider, Sean Nunan, on to the Board, and the Newspaper which was established with other people’s money for the Irish Nation, had become a family business. It does not reflect well on the other senior members of Fianna Fail at that time that this happened right under their very noses; ‘The Chief had treated them and the Party with the utmost contempt and was allowed to get away with it. Vivion had no qualifications to run a newspaper but he took the job and continued with his father’s “fiduciary” falsehood. In 1962 he was given the controlling ‘B’ Shares in the US Corporation and the de Valera takeover was complete; significantly, it had not cost the family one penny.

The Irish Press Limited paid its first dividends in 1973 but at that stage, nearly half a century later, a great number of the shareholders were dead or missing. US investors, who had been duped into accepting ” Certificates of Participation” in the Irish Press Corporation, had been told over the years that their shares had no value, despite there being large sums on deposit, and it was 1980 before a dividend was finally declared. By this time, five decades later, the vast majority of the original investors were either dead or untraceable, but, although ‘The Chief had died in 1975, the de Valera family was still there to pocket the windfall.

The large sum of money still on deposit in the US to this day, also belongs to the original investors but one can guess as to where it will finally wind up. Eamonn de Valera had quietly become an immensely wealthy man during his political career but when he died his Estate [ £2,800 declared] was liable for one penny in death duties. He remained true to himself to the end; even in death he was not going to pay.

In the early 1980s Vivion stepped dmvn and surprised absolutely nobody by nominating his son, Eamonn, to succeed him, another man with no experience or expertise in running a newspaper. In 1985 the 200 ‘B’ Shares in the US Corporation were owned by de Valera’s youngest son, Terry, and his grandson, Eamonn. Terry sold his 100 shares to Eamonn and received a princely £225,000. The original people who had answered the call and entrusted their hard earned savings to Eamonn de Valera for ‘The Cause’ got “no penny nor dollar nor cent”.

The economic downturn of the 1980s, coupled with a lack of vision and a tight fisted lack of investment by an inept management, brought about a steady decline in the sales and revenue of the paper and, finally, in April 1995, the last edition of the Irish Press was printed; Controlling Director, Eamonn de Valera, had decided to cease publication. Six hundred employees lost their jobs, but the Directors kept theirs and to this day continue to pay themselves substantial fees. The business, which is still worth millions of Euros in assets, publishes nothing but continues to trade selectively in a sort of twilight zone through a “very liquid and very solvent little investment company”, Irish Press PLC, with the Controlling Director still depending on the shares purloined by his grand-father to secure his authority and impose his will. Dividends are now paid regularly but, with the vast majority of shareholders dead or missing, it is plain just who is benefiting.

In fact the only family to benefit in any way from The Irish Press Limited, the Irish National Newspaper set up to” break the stranglehold of the alien press” in Ireland was and still is the deValera family.

After decades of pretending that Michael Collins had never existed, Eamonn de Valera, in 1966, is quoted as saying ‘ It is my considered opinion that in the fullness of time history will record the greatness of Collins and it will be recorded at my expense’. He had lived a lie for most of his life but knew in his heart that all would be revealed in the end. It is now an obvious and sad fact that Eamonn de Valera, The Chief, betrayed the idealism, patriotism and sacrifices of the thousands of people who believed in him and entrusted to him their hard earned savings to” help set Old Ireland Free”. He never once lost sight of what we now know to have become his prime objectives in life i.e. ‘MONEY and POWER ; He achieved both.

Charles J. Haughey was not our first corrupt Taoiseach, nor, it would appear, our last; and in fairness to him, apart from plundering Party funds with the assistance of another future Taoiseach, he only took money from people who had plenty of it and gave it to him willingly, for reasons of their own. Not for Champagne Charlie the widow’s mite.

Eamonn de Valera left the country almost bankrupt when he stepped down as Taoiseach on January 15th,1959; 50 years later his successors, Bertie Ahern and Brian Cowen, have quite possibly gone one better.

There is a handsome and historic Doctorate waiting for the intrepid student who produces a Thesis entitled ‘De Valera and his Money’. Will we ever see it? We can only live in hope.

(Reference: RTE Documentary)