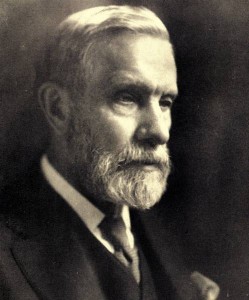

John Devoy

The Fenian: John Devoy

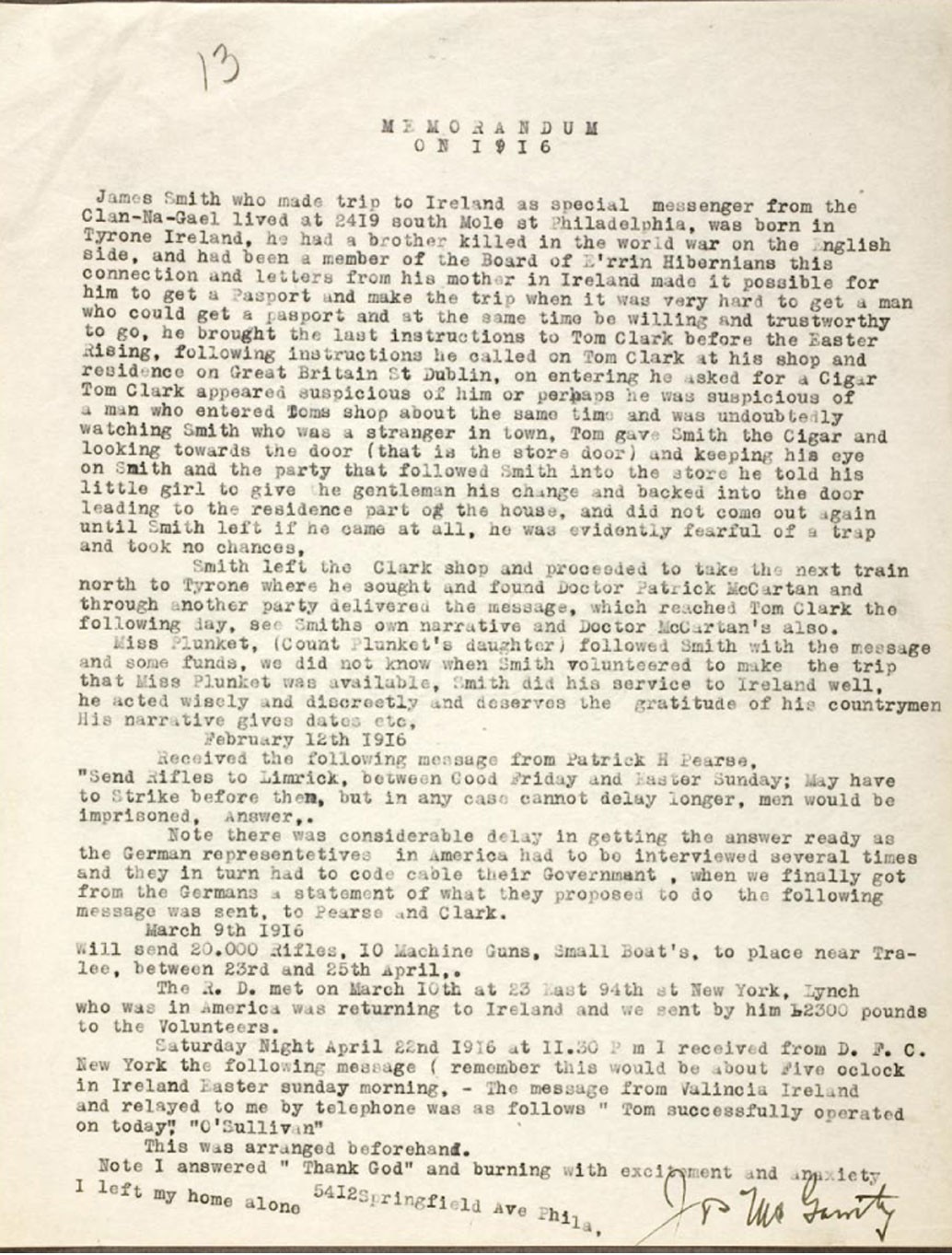

Clan na Gael directly contributed to the Rising by providing American funding and arms for the Irish Volunteers.

John Devoy (1842-1928) was born into a family living in a cottage on half an acre at Kill, Co. Kildare. The family moved to Dublin where he was educated by the Christian Brothers at O’Connell’s Schools on North Richmond Street, at Marlborough Street model school, and at Strand Street model school, where he became a paid monitor for a couple of years before finding more remunerative employment as a clerk.

Devoy came into contact with political activists while learning Irish at evening classes, eventually being sworn into the secret society known as the Fenians in 1861. After a year with the French Foreign Legion in Algeria, he settled in Naas, Co. Kildare, where he worked as a Fenian organiser. The Fenian leader, James Stephens, next entrusted him with the recruitment of Irishmen in British regiments. He was eventually arrested in February 1866 and sentenced to fifteen years penal servitude; he was released in 1871, having served four years in various British prisons. On his release he emigrated to the United States.

Around 1873 Devoy joined Clan na Gael (founded in 1867 ) which under his leadership became the premier Irish-American nationalist organisation. One of his most spectacular coups was the daring rescue of six Fenians from penal servitude in Fremantle, Australia in 1876 by means of the whaler Catalpa. He engineered an agreement with the other major Irish separatist organisation, the Irish Republican Brotherhood, creating a joint revolutionary directory. Under his leadership, Clan na Gael contributed significant financial support to the Land League in the period 1879-81. It also supported Parnell’s Irish Parliamentary Party, but considered Home Rule an inadequate settlement and only of use as a stepping stone to complete independence.

Devoy worked mainly as a journalist in New York. In 1903 he established and edited a successful paper, the Gaelic American, with Tom Clarke as assistant editor for a period. Under the leadership of Devoy, Clan na Gael supported many of the Irish nationalist projects of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, including the Gaelic Athletic Association, the Gaelic League, Arthur Griffith’s United Irishman, and the Irish Volunteers. Regarding the Irish Volunteers as potentially an army of insurrection, the Clan supported the organisation with funding and consignments of arms; it is believed to have contributed $100,000 towards the Rising between 1913 and 1916. The Clan also worked hard to promote anti-British feeling and so prevent the entry of the United States into the war on the side of Britain.

In 1914, Devoy took a leading role in promoting a lecture tour of the United States by Patrick Pearse to save Saint Enda’s School from closure. That same year he hosted Roger Casement, later funding his mission to Germany to procure arms and to recruit Irish prisoners of war for service in the proposed insurrection. He was also involved in exploiting the funeral in Dublin (1 August 1915) of the veteran Fenian, Jeremiah O’Ronovan ‘Rossa’, who died in New York, as an occasion for the outpouring of extremist national sentiment.

Devoy was kept abreast of plans for the 1916 Rising, being in the confidence particularly of Clarke, Pearse and Joseph Plunkett. Although then in his seventies, he wanted to take part, being thwarted only by his failure to get the necessary travel papers in time.

The Easter Rising

Eventually Devoy’s persistence in educating Americans about the movement would pay off for Ireland. Devoy, along with Roger Casement, was responsible for the drawing together of the American and German threads in the years leading up to the Easter Rising. Devoy’s Clan na Gael became the largest single financier of both the Easter Rising and the War of Independence.

Often described as egotistical and temperamental, Devoy had numerous long-running disputes with many Irish leaders, including James Larkin — whom Devoy believed was a British agent — and Éamon de Valera — whom Devoy saw as a dangerous amateur in American affairs, causing diminished support from Irish-Americans during his US visit in 1919.

Yet, despite his supposed stubbornness and egotism, Devoy never wavered in his quest for Irish freedom. He is considered by many to be the greatest of Fenians. He accomplished what he set out to do — it was John Devoy who made the Irish cause an international issue; and it was John Devoy who was able to enlist American public support on behalf of the small island of Ireland. Devoy asked America to give only what it demanded of itself — “genuine democracy and authentic republicanism”

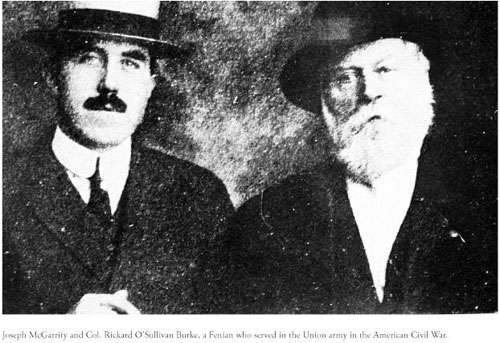

Joseph McGarrity

Old days: we’ll soon be fighting,

Head to the storm as we faced it before.

While there are Irish there’s bound to be fighting

As long as the Saxon remains on our shore.

Joseph McGarrity, “Old Days,” Celtic Moods and Memories.

Joseph McGarrity was born on March 28, 1874, on the outskirts of the Irish village of Carrickmore, county Tyrone, an area of Ulster with a centuries-long history of republican resistance to English rule. Despite growing up quite poor, McGarrity, in his unpublished memoirs, characterizes his childhood household as “a happy one,” filled with fiddle music and singing, folk tales of fairies, leprechauns and banshees, and spirited conversation. As a child McGarrity would have overheard his father and other adults discussing the pressing Irish political issues of the day including land reform, the exploits of Charles Stewart Parnell, and the long-simmering debates over Home Rule. By age 17 McGarrity was already taking, as he describes it, “considerable interest in the political life of the country, going to meetings and listening to tales of the Fenians in the Penal days, the executions etc.” These stories of heroic Fenian rebels captured the young McGarrity’s imagination and would continue to shape and nourish his dedication to a Fenian ideal of Irish nationhood throughout his life.

The Fenians, also known as the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), were a secret organization dedicated to the liberation of Ireland through armed revolution. Formed in the 1850’s, they staged an insurrection in 1867 that was quickly crushed. Despite its failure, the Fenian Uprising led to a renewal of the Irish revolutionary tradition and engendered a new generation of nationalist martyrs to inspire young Irish republicans some of whom, like Jospeh McGarrity, carried their politics with them when they left Ireland to begin a new life in America. After arriving in Philadelphia, McGarrity remained active in his support of the Irish nationalist cause. In 1893 he joined the Clan-na- Gael, the US counterpart of the IRB, and in the decades that followed McGarrity would rise to become chairman of the Executive of the organization and widely recognized as one of the most powerful leaders of the Irish separatist movement in the United States.

McGarrity’s Fenian temperament was characterized by a combination of an historical imagination steeped in nostalgia for the heroic actions and figures of the Irish past, and an uncompromising commitment to the core Fenian political doctrine that the ultimate goal of a free and united Ireland could only be achieved through physical force. The spirit of Irish nationhood, for McGarrity, was not reducible to a devolved parliament, a constitutional question or even the ownership of the land; rather it survived embodied in the history of the armed struggle for Irish independence. The appeal and power which the romantic-heroic mythology of Irish republican nationalism held for McGarrity is clear in poems like “Fenian Days,” which McGarrity commissioned to be set to music, and in the vivid rhetorical style that animates many of his speeches and letters.

A firm believer in the power of myth and memory to rouse patriotic sentiment, McGarrity regularly invokes the names of nationalist heroes and martyrs in his poetry, from Wolf Tone, William Orr, and Robert Emmet to Padraig Pearce, Roger Casement, and James Connolly. Characteristically, McGarrity celebrates an ideal of heroic sacrifice in “Fenian Days,” grounding his Fenian convictions in redemptive terms that draw on his Roman Catholic faith:

Blood of Irish hero ages

Spirits of our saints and sages

Help us pay the despot’s wages,

Speed our sword to strike the blow.

McGarrity was particularly proud of “Fenian Days” and, as Marie Tarpey notes, expressed in a letter to his good friend and fellow Carrickmore man Patrick McCartan how heartened he was to hear that his old schoolmaster, Master Marshall, had approved of the poem.

Joseph McGarrity’s Pub in Philadelphia