Treaty Plenipotentiaries

Treaty Plenipotentiaries

From left to right: Arthur Griffith, Edmund Duggan, Michael Collins, Robert Barton, (at back) Erskine Childers (sec), George Gavin Duffy and John Chartres (sec).

Éamon de Valera sent the Irish plenipotentiaries to the 1921 negotiations in London with several draft treaties and secret instructions from the cabinet. The Irish delegates set up headquarters in 22 Hans Place, Knightsbridge. The first two weeks of the negotiations were spent in formal sessions. Upon the request of Arthur Griffith and Michael Collins, the two delegations began informal negotiations, in which only two members of each negotiating team were allowed to attend. On the Irish side, these members were always Collins and Griffith, while on the British side, Neville Chamberlain always attended, though the second British negotiator would vary from day to day. In late November, the Irish delegation returned to Dublin to consult the cabinet according to their instructions.

From left to right: Arthur Griffith, Edmund Duggan, Michael Collins, Robert Barton, (at back) Erskine Childers (sec), George Gavin Duffy and John Chartres (sec).

Éamon de Valera sent the Irish plenipotentiaries to the 1921 negotiations in London with several draft treaties and secret instructions from the cabinet. The Irish delegates set up headquarters in 22 Hans Place, Knightsbridge. The first two weeks of the negotiations were spent in formal sessions. Upon the request of Arthur Griffith and Michael Collins, the two delegations began informal negotiations, in which only two members of each negotiating team were allowed to attend. On the Irish side, these members were always Collins and Griffith, while on the British side, Neville Chamberlain always attended, though the second British negotiator would vary from day to day. In late November, the Irish delegation returned to Dublin to consult the cabinet according to their instructions.

When they returned, Collins and Griffith hammered out the final details of the treaty, which included British concessions on the wording of the oath and the defence and trade clauses, along with the addition of a Boundary Commission to the treaty and a clause upholding Irish unity. Collins and Griffith in turn convinced the other plenipotentiaries to sign the treaty. The final decisions to sign the Treaty was made in private discussions at 22 Hans Place at 11.15am on 5 December 1921. Negotiations closed by signing on at 2.20am 6 December 1921. It has been said that at the last minute Lloyd George threatened a renewal of war if the Treaty was not signed at once, but this was not mentioned as a threat in the Irish memorandum about the close of negotiations, merely a reflection of the reality. Éamon de Valera called a cabinet meeting to discuss the treaty on 8th December, where he came out against the treaty as signed. The cabinet decided by 5 votes to 3 to recommend the Treaty to the Dáil on 14 December.

Eamon de Valera T.D.

First President of the Republic addressing the nation on the eve of the

London Negotiations on October 7, 1921

“Our delegates are keenly conscious of their responsibility. They must be made to feel that a united nation has confidence in them and will support them unflinchingly. The delegates are aware thai no wisdom of theirs, no ability of theirs, will suffice. They indulge therefore, in no foolish hopes nor should the country indulge in these. The power against us will use every artifice it knows in the hope of dispiriting, dividing and weakening us. The unity that is essential will be best maintained by an unwaver-ing faith in those who have been deputed to act on the nation’s behalf, and in a con-fidence manifesting itself as hitherto in eloquent discipline. It is no wonder that the older men among us, who remember the bitterness of political divisions thirty years ago, should be afraid of cleavage. But we who have worked together as brothers ought not to be afraid to face each other in argument, and to abide by whatever the result may be. We are asking the delegates to do what our army has been unable to do – to get the British out of the country. ”On October 25 I sent the following memo (No 7 in our documents! to the Chairman of the delegation in London: ‘I received the minutes of the 7th session and your letter of October 24. We are all here at one that there can be no question of our asking the Irish people to enter into an Irish arrangement which would make them sub-jects of the Crown, or demand from them allegiance to the British King. If war is the alternative, we can only face it, and the sooner the other side is made to realise that the better.”

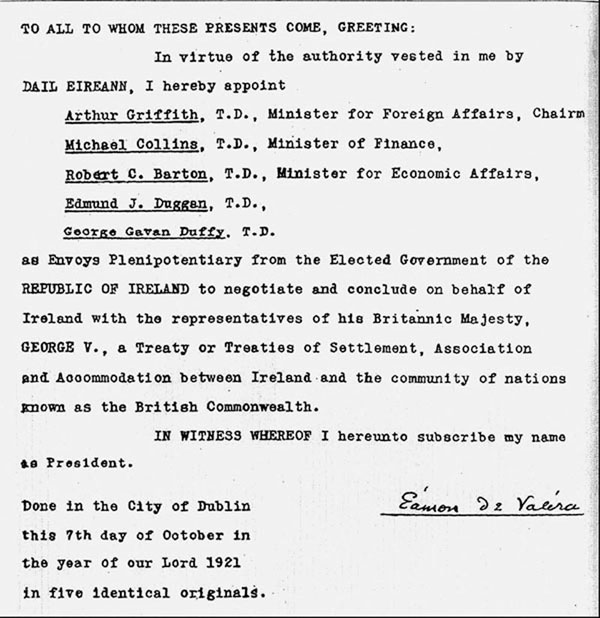

COPY OF THE ORIGINAL CREDENTIALS TAKEN TO LONDON BY THE PLENIPOTENTIARIES

Arthur Griffith, T.D.

Chairman of the Irish Plenipotentiaries

“Before we went we were told we might be made scapegoats of, I was prepared to be a scape-goat, if even one per cent could be added to Ireland’s gain. Before I left I said plainly at a Cabinet meeting that if I were to a go to London I could not get a Republic, that I would try for it, ceitainly, but I did not think I would be able to bring it back. If we were to get a Republic and nothing else the thing could have been dismissed in six lines by writ-ing to the British Premier and telling him that we would meet him only on the condition that he recognised the Republic. This Treaty is the first ever concluded between the people of Ireland and England”. ”It is also the first Treaty that hands back to Ireland the right to govern itself, to work out its own career and its own des-tiny. It gives our people solid ground upon which to stand: for Ireland has been a quaking bog for three hundred years, with no foothold for its people.

I live in a world of reality. I would like to make my dreams and all the dreams of my people come true – But we have to face facts -above all the fact that our country is not equal in physical strength to England. ”So I went to London without any illusions, and told President de Valera that I could not bring back a Republic- We had power to sign anything we considered it well to sign, and the power of the Dail was the power of ratification. That was the position on the Saturday, We went back to London and met the British Cabinet on Sunday, and fought straight up and down all day. We nearly broke on Sunday night. As a matter of fact we did make a break, but we went back again on the Monday morning and started it once more. In the end, Lloyd George was sending the final reply to Craig, who had called his Parliament for the Tuesday. I say we fought all day, and Lloyd George had two letters written to Craig, which were going over at ten o’clock that night. One letter informed him that negotiations with us were broken off, and the other was putting the proposal to him which is now our Treaty. We, therefore, had no alternative, and had.to face the decision. I tried hard to get it put back for another week, so as to return to An Dail. But I could not get it done. I had absolutely no doubt in my mind that the issue was peace or renewed war in Ireland:and this was also the impression of every mem-ber of our delegation. War would have started afresh not with any formal declaration, but with casual shooting on one side or the other. Mr de Valera came back from America when I was in prison, and he advised the members of An Dail to ease off the war somewhat.

It is a fact that he entered into negotiations with the British Government while I was in gaol, describing himself, not as President of the Irish Republic, but as the spokesman of the Irish people. ”When our Cabinet sent me to London, I distinctly said that ‘neither I nor any other man could bring back a Republic, and de Valera admitted to me that it could not be done. He said be was no doctrinaire Republican, and he sent a deputy to the United States to make the new situation clear. Moreover, de Valera appealed to me before I went to London – “Get me out of the straight-jacket of the Irish Republic – I cannot get it.” Every night, from Hans Place in London, a special courier was sent to Mr de Valera, so that he had on his breakfast-table news of all that had passed.

Michael Collins T,D

Explaining details of the hows and whys of the decisions taken by the Plenipotentiaries

“Some of us were sent to London very much against our wishes. That is well known to all. It is absurd to claim that we went there to dictale terms to a van-quished foe. If we had vanquished the British, it is they who would have to come here and sue for peace. remember we went back to Dublin on that momentous Saturday to a meeting of our Cabinel, We left that meeting with certain impressions, and put these on paper to be handed to the British Delegates. We went away with a document which none of us would sign.

The matter had to be faced, and if in the meantime pro-posals were presented which we could sign, there was no opportu-nity of referring these to Dublin. On the Monday nigh! we did arrive at a conclusion to which we thought all would agree, and to which we did say “Yes” across the table at a very late hour. We knew the rejection of the Treaty meant a declaration of war, and a continuance of it until Ireland was able to beat the British Empire. In the secret sessions of the Dail we were treated to many harangues about principle – “Go another round in the race”, Mr de Valera urged, in effect, and who knows that the other fellow will be able to finish it? Yes, who knows? And supposing he were able to finish it – what then? Was the safety and future of the Irish nation to be staked on such a gamble?”

Edmund J Duggan T.D

One of the delagates at the Treaty discussions in London

“I was not threatened by Lloyd George, nor did he shake any papers in my face, I signed the Peace Treaty in the quiet seclusion of 22 Hans Place, and that with the fullest consciousness of my responsibilities to Ireland – the living and the dead- It has been suggested that we delegates were bluffed and intimidated, and that Michael Collins was frightened and cowed by the Prime Minister shaking a piece of paper in his face. Well, for two years much more effective means to cow Michael Collins were tried, and we know they did not succeed. It was suggested also that two months residence in London had demoralised us to such an extent as to make us forget our duty to our people. There was one dominating factor in my mind at the time I put my name to this Treaty, and that was that Britain was stronger militarily than Ireland. Another charge made against us was that we had disobeyed our instructions by not coming back from Downing Street on the Sunday night and submitting the draft Treaty to the Cabinet before signing it. But the Cabinet knew well that a week’s notice was given, and that we would have to give a certain answer on a certain date.

We did come to our Cabinet on the Saturday night, and had to rush hack at once to London to present the new proposals. These, of course, were promptly rejected by the British, as we told our Cabinet they would be. Negotiations were then reopened and eventually on the Monday night we got two hours in which to give a definite “Yes” of “No” answer. Some people appear to have thought we brought home a bagful of sample treaties, from which Ireland might pick and choose. As it happened, the Treaty as signed gave us our country, and ridded us entirely of the enemy and of all his machinery of government.”

Kevin O’Higgins T.D

(Vice-President of the Executive Council)

“If we really meant to stand for the hundred per cent of our war programme, we should have fought on, demanding unconditional evacuation by the British. If they refused, we should have driven them into the sea, or perished to the last man and woman, in the attempt. In fact, however we did agree to a Truce, and a great many people were mightily relieved when it came. Moreover, we sent five Plenipotentiaries to negotiate, after Mr Lloyd George had clearly stated his fundamental condition. The situation was well understood by our Cabinet, and by Dail Eireann itself. Mr de Valera made it perfect-ly clear by explaining to us in private that: “It had really booiled down to a question of what we are going to sell the cow for?” He apologised for the metaphor, saying it was crude, but expressive. No one misunderstood him. The fighting machine we had set up in Ireland and called ‘a Republic’ was excellent – as a fighting machine. And the outlawed Dail, with its Civil Departments and its guerilla Army, had given a very good account of itself. I do not want to be taken as blaming Mr de Valera for giving up the Republic, and more particularly when he drafted Document no 2. It is true that in public he was not so outspoken as he was with us in private. In public he merely said: ‘We are not Republican doctrinaires, and we do not negotiate to save faces’, This was the diplomatic intimation to the British that the ‘cow’ was for sale. It follows, therefore, that Mr de Valera’s quarrel with Michael Collins and Arthur Griffith was not based on the fact that the ‘cow’ had been sold: It was simply a question of the price. And Mr de Valera’s price was Document no 2 with its oath to recognise the King of England as Head of the Associated States, Ireland being one of these states, and its yearly money voted to the King’s personnel revenue, in token of that recognition. Our Plenipotentiaries and I wish to stress that word – were unable to agree that the difference between Document No 2 and the Treaty was one for which they would be justified in plunging their country back into war against overwhelming odds-, So our Plenipotentiaries faced the facts: sometimes it takes more courage to face facts than it does to face machine guns- It became a question of securing evacuation, on terms: The alternative was a resumption, of war against, odds with the possibility of a ‘Sherman’s March’ of the enemy in Ireland, of which Mr de Valera “had.already warned the Dail.”

Aspirations for the future

Michael Collins, August 1922

The following thoughts of Michael Collins which he penned in August 1922 give an insight into his opinions on Irish people; their aims and aspirations; and on his own hopes for a nation rich in mind and body and character which would have its priorities right :- ”The chance that materialism will take possession of the Irish people is no more likely in a free Ireland under the Free State than it would be in a free Ireland under a Republic or any other form of Government. It is in the hands of the Irish people themselves. What we hope for in the new Ireland is to have such material welfare as will give the Irish spirit freedom to reach out to the higher things in which the spirit finds its satisfaction. We want such widely diffused prosperity that the Irish people will not be crushed by destitution into living practically the lives of the beasts. ”Our object in building up the country economically must not be lost sight of. That object is not to be able to boast of enormous wealth or of a great volume of trade for their own sake. It is not to see our country covered with smoking chimneys and factories.

It is not to show a great national balance sheet, nor to point to a people producing wealth with the self-obliteration of a hive of bees. The real riches of the Irish nation will be the men and women of the Irish nation the extent to which they are rich in body and mind and character. ”What we want is the opportunity for everyone to be able to produce sufficient wealth to ensure these advantages for themselves. We must be true to facts if we would achieve anything in this life.‘We must be true to our ideal, if we would achieve anything worthy. The Ireland to which we are true, to which we are devoted and faithful, is the ideal Ireland, which means there is always something more to strive for. The true devotion lies not in melodramatic defiance or self-sacrifice for something falsely said to exist, or for mere words and formalities, which are empty, and which might be but the house newly swept and garnished to which seven worse devils entered in. It is the steady, earnest effort in face of actual possibilities towards the solid achievement of our hopes and visions, the laying of stone upon stone of a building which is actual and in accordance with the ideal pattern.

In this way, what we can do in our time; being done in faithfulness to the tradition of the past, and to the vision of the future; becomes significant and glorified beyond what it is if looked at as only the day’s momentary partial work. ”This is where our Irish temperament, tenacity of the past, its vivid sense of past and future greatness, readiness for personal sacrifice, belief and pride in our race, can play an unique part, if it can stand out in its intellectual and moral strength, and shake off the weaknesses which long generations of subjection and inaction have imposed upon it.” ‘Let the nation show its true and best character; use its courage, tenacity, clear swift intellect; its pride in the service of the nation ideal as our reason directs us.”