British Withdrawl (1922)

-

BRITISH WITHDRAWL – (A Sunburst and Clouds 1922) – Tim Healy

The outgoing British garrisons, embarrassed by this civil strife, unintentionally bred trouble for the Free State. Their officers had been harried and kidnapped and many of them slain, so no friendly feelings towards the incoming authority could be cherished. Munitions and barracks were handed over (unwittingly) to foes hostile to the Treaty in some cases. The departing regiments knew little of the political hue of their successors, and gave up places of strength, undiscerning differences of politics.

To no fault of theirs was due the case of Limerick, where the question of the control of the Castle of King John and other barracks led to civil war. The outgoing British commanders asked extremists to take charge, and were refused. Collins therefore requested a Clare battalion to fill the gap. This aroused jealousy amongst the logicians who had declined responsibility.

When the Clare contingent marched in, the opponents of the Treaty mustered supporters from all parts of Ireland, and threatened fight unless the Castle was entrusted to them. They could easily have been dealt with, but so reluctant was Collins to spill blood that he gave them control. A few shots then would have spared Ireland two years of strife.

Having triumphed in Limerick, the mutineers thought that bluff would succeed elsewhere. The censorship (now native) misled public opinion by hindering knowledge of the truth. De Valera told the Dublin correspondent of the Manchester Guardian that “his army” would put the Provisional Government out in a month, and emphasized this prophecy by banging the table with his fist.

I had crossed to London at this epoch, and on my return wrote:

Chapelizod,

20th March, 1922.

“I met Bonar Law yesterday, and I could see he is bitter against any change being made in the Ulster Boundary. If Lloyd George resigns, Bonar will be Prime Minister, and will hardly appoint a friendly umpire of the Boundary Commission.

The Government have agreed to Lord Shaw acting as the “Rebellion Losses” chairman. Duggan wants me to appear at the inquiry as counsel.”

At the request of one of de Valera’s friends, I called at his office to remonstrate with him against stirring up armed resistance. Beforehand I saw Collins, who told me it was useless. Still, I went, and gave my brother the following account of the visit:

Chapelizod,

25th March, 1922.

“I saw de Valera on Thursday and tried to reason with him. He was very civil, but I could see their plan is to stop the elections, In this they will be defeated, except in a few districts. Then they will become like the Parnellite faction 30 years ago, only worse. Harry Boland kept the door of de Valera’s room, and I left sensing tragedy.”

I begged de Valera to discountenance a conventicle of his army “chiefs” who were about to meet in Dublin. Griffith proclaimed the gathering an “illegal assembly,” but de Valera protested to me that he had nothing to do with the “army.”

I told him he would be a sorry man in 12 months’ time if he lent himself to force. He replied he didn’t think so. I remarked, “I am an expert in ‘splits,’ and believe I can forecast the result better than you.” He smiled. I wrote Maurice:

Chapelizod,

27th March, 1922.

De Valera’s military clique met yesterday at the Mansion House to capture the Army, but made a poor display in point of influence and numbers. Yet they will give trouble, as jealousy is always potent.

Collins’s speech in Waterford was excellent. He sent a man to consult me about the Belfast “Specials,” an illegal force, I think, unless appointed by the Competent Military Authority under the Restoration of Order Regulations.”

Chapelizod,

31st March, 1922.

“In arranging for the Treaty, blundering has led to the present uncertainties. If the British had provided for a continuation of their occupation until an election enabled a lawful Government to be established, we should not be in the mess we are.

Their treatment of the police, both in Dublin and in the country, has taken all the heart out of the preservers of order, and the wonder is that there is not a greater rampancy of crime. I suppose it is the “dole” to the unemployed that is keeping the poor quiet.

In this village, the distillery is closed owing to the heavy whisky tax, and hundreds are out of work. Yet I have not heard of a single theft, nor has the number of beggars calling on me increased. I wish the rest of the world were as quiet and orderly as Dublin, although we have two hostile armed forces coping with one another.”

De Valera affected to believe that the British evacuation was a sham and would never take place. The Provisional Government therefore urged the War Office to hurry off the garrison. The cunning of their opponents lay in the hope that their “resolutes” could fall upon the raw levies which were all that Collins and Griffith had at their command.

When Griffith proclaimed illegal the meeting of de Valera’s army chiefs in Dublin, I besought Collins to disperse them. Good nature again, as in Limerick, prevailed over good sense. For three months little was done to check the mutineers. Patriotism was played upon by futile “negotiations.”

The Freeman published, on 26th March, an account of the secret debate of the mutineers supplied by the Provisional Government, whereupon Rory O’Connor sallied from the Four Courts and smashed its machinery. He had been levying toll on the civil population for weeks. On the day he entered the Courts I implored Collins to drive him out, which then could easily have been done.

Four Courts Attack

He was son of the Solicitor to the British Congested Districts Board, and a Corporation official. Seizing the Courts began the Civil War. He also put a garrison into Kilmainham Jail, where a few British soldiers remained, but when General Macready notified him that he would attack unless they withdrew, they left. The Ballast Office, too, was “taken,” but its employés, thrown out of work by the commotion, assembled to jeer at the entrants, who then skedaddled. The difference in morale between the insurgents of 1916 against the British and those of 1922 against their own countrymen showed that the new forces had no heart in the contest.

In June, O’Connor arrested General O’Connell, of the National Army, and this at length determined Collins to end the reign of lawlessness. The impatience of Mr. Churchill led him into a telegram which made it arguable that he was the instigator of attack.

Before this (28th June, 1922) de Valera’s forces turned machine-guns on the National troops in Wellington Barracks, Dublin (formerly Richmond Prison-now called Griffith Barracks). One of the Irregular leaders was inside at the time arguing for a compromise, and deplored the fusillade as certain to bring about unhappy consequences.

A general election had meanwhile ratified the acceptance of the Treaty, despite violence. As a last resort against disorder Collins, after negotiating for two hours, shelled the Four Courts. Rory O’Connor, on being called upon to surrender, issued this defiance:

[The Four Courts during the engagement with the anti-treaty forces]

“9 a.m., 28th June, 1922.

At 3.40 this morning we received a note signed by Tom Ennis demanding on behalf of “The Government” our surrender at 4 p.m., when he would attack.

He opened fire at 4.7 in the name of his Government, with rifle, machine and field pieces.

The boys are glorious, and will fight for the Republic to the end. How long will our misguided former comrades outside attach those who stand for Ireland alone? Three casualties so far, all slight. Father Albert and Father Dominic with us here. Our love to all comrades outside, and the brave boys especially of the Dublin Brigade.

(Signed) Rory O’Connor, Major-General, I.R.A. Four Courts.”

The four Courts following the explosions.

It was an overture to an inglorious symphony. After a feeble resistance “Rory” hoisted the white Flag without the loss of a man. Before the surrender he laid land-mines, filled with explosives timed to burst two hours after. Up to that, the Four Courts was little damaged, and the Record Office, with its precious historical collections, lay intact. The mines went off, when he and his braves were safe in prison. They shattered the fabric of the Courts and destroyed the Record Office. Twenty Free State soldiers were maimed, many for life, yet no punishment was exacted for this treacherous breach of the rules of war.

On the 4th July, 1922, the National Army G.H.Q. deplored such unsoldierly conduct: “Other traps were laid with the intention of slaughtering our troops after their occupation of the building, but this was the only one that succeeded. One of these traps was a mine concealed in a typewriter cover.

In a letter dated 30th June, addressed “O/C 5,” Mr. Oscar Trainer, a leader of the Irregulars, wrote: “Congratulations on your bomb. If you have any more of these, let me know.”

A conversation is also recorded between an officer and an Irregular, who expressed sorrow that more soldiers did not suffer, yet the Cork Examiner, seized by “Republicans,” described the defence as another Verdun!

De Valera now began a new offensive. Business premises in O’Connell Street, Dublin, were occupied by him and his abettors. The seizure of Government buildings might be palliated, but why merchants and hotel-keepers should have their houses ruined over a political dispute is unsolvable. Men who would disdain to pick a pocket were found ready to destroy the undertakings of traders and deprive their employés of work in a futile struggle as to dialectics concerning the difference between the Treaty and “Document No.2.”

To uphold his contentions, de Valera seized the Gresham, Granville, Hammam, Edinboro’ and Moran Hotels. When the first-named premises went alight under gunfire after three or four days, he withdrew by a back-way. His colleague, Cahal Brugha, fought to the end, and tasted death, firing his last round. However mistaken, he was a gallant soul.

Captured letters confessed de Valera’s weakness. He wrote that he was sorry for not repudiating Rory O’Connor, while F. Aiken, Chief of Staff, bewailed that “we always thought the enemy would not go so far.” I wrote my brother:

Chapelizod,

7th July, 1922.

“We have heard nothing from Cork or the country except the meagre paragraphs in the Press.

The Great Southern Railway is cut in several places, but I am sending this because I was informed by the Post Office that there is communication with Cork. Our telephone was restored to-day.

It is better for me to make no comment on the events of last week. The Four Courts explosion shook this house, although miles away. It must have represented an awful quantity of dynamite.”

[Documents from the Four Court Archives scattered to the four corners of Ireland]

The destruction of the Record Office was abominable. It contained parchments reaching back to the Danish invasions, including a grant from the Danish Ring of Dublin of the lands of Kinsealy to provide candles for the altar of Christ Church. Many of the Gaelic decrees of the Brehons also went up in smoke. It was largely founded, or at least chiefly arranged, by Sir Samuel Ferguson, the Ulster poet, whose noble versification of Gaelic themes delights the Irish heart. He could not foresee the sad sequel for Ireland as he sang of the day:

I wrote Maurice:

Dublin,

8th July, 1922.

“When Terror heads Oppression’s rout And Freedom cheers behind!”

I was glad to read to-day that the “Cork area is quiet,” but whether this is the peace of Republican domination or of Free State rule, is not explained!”

The fact was that Cork City and the surrounding areas were held by the Republicans, to whom the Cork Barracks had been handed over by British officers, unacquainted with the divisions in the hitherto serried ranks of Sinn Feiners.

Chapelizod,

13th July, 1922.

“I am glad you are safe. Jasper Tully was with me last night and says the Republican tactics will be to retreat when attacked, and that he was told this by an officer of theirs.

Yet they can’t go on retreating, as it would demoralize their men and encourage their opponents. They don’t show fight as far as the news which is allowed to reach us indicates.

In the Gresham Hotel, Archbishop Byrne in vain implored de Valera not to keep up the conflict. His Grace visited the hotel with the Lord Mayor.

It has been comparatively peaceful in our neighbourhood, but in King’s Inns I heard shots close by.

It is so schoolboy-like! The Republicans would rather have the English back than put up with the Free State. Their disregard for the comfort, convenience, liberty and happiness of the public is saddening.”

I still marvel after six years how the champions of the Treaty won – with Griffith dead; two of the signatories doubtful, or asserting that their approval was obtained by duress; and Collins forced to take up arms against the violent aggression of its assailants, and soon himself to be slain. Of the difficulties of that time I commented to my brother:

Chapelizod,

15th July, 1922.

“Carson’s statement that only “loyalists” suffered in the Dublin fires is beyond anything. The Catholic Truth Society’s office was destroyed, and J. & G. Campbell’s wine-place burnt.

So the notion that the mutineers “picked and chose” is impossible, even if they had a mind. The Hammam and Gresham Hotels were the haunts of Nationalists, and before the outbreak, Collins and Duggan made the Gresham their headquarters. These “went west” too.”

Chapelizod,

8th August, 1922.

“We were disturbed yesterday to read of your “deportation” by de Valera, but you are right in treating it as you do.

If I had the least notion you were to be in London on Saturday, I should have stayed there. Your wisest plan is to come here as soon as you have seen Stratford-on-Avon.”

My brother was put on a steamer at the point of the revolver because he advised the merchants of Cork that income tax demands, if paid to the Republicans, would not release them from liability to the Free State when the City was retaken. For this advice, or for the two months’ absence from his business which it cost him, he never asked the customary six-and-eightpence!

The office of the Cork Examiner was seized, and a governess of the owner’s children (Miss Mary MacSwiney) was installed as editress. Her “war correspondents” congested with paper with accounts of glorious Republican vistories.

Levies on Cork banks and the local Custom House took place. Jewellers impressed Republican “hall-marks” on silverware. The burning of Cork the year before by the Black-and-Tans had so upset the population that no one knew on which side truth could be looked for.

De Valera was driven out of Cork by a handful of Free State soldiers. Before he abandoned the City the pier at Ballycotton was wrecked to prevent a landing of troops. He retreated to Mallow, and at Childers’ behest the railway viaduct there was blown up. De Valera quartered himself on the house of the assistant County Surveyor, Richard O’Connor, who implored him not to allow this, but he answered, “It will save thousands of lives!”

Childers planned the economic bankruptcy of Ireland – a country less his own than it was de Valera’s.

An attempt to destroy the Mallow road-bridge across the Blackwater was foiled by the pluck of the clergy, Catholic and Protestant. They assembled the people, who held it en masse, defying threats.

Then de Valera, hunted towards Tipperary, occupied at Cahir the house of Colonel Charteris. He stayed there a fortnight, and on leaving inscribed his name in the Visitors’ Book!

Meanwhile, the Castle at Mitchelstown was destroyed. The attempt on the Duke of Devonshire’s seat at Lismore failed. No act of heroism to the credit of the insurgents is known to me save the stand of Cathal Brugha. If I knew anything in their favour, in spite of their destruction of thirty millions’ worth of property, I should set it down. When the Free State Government gave them an amnesty, they declared they regretted nothing, although the murder of Dr. O’Higgins (father of Kevin O’Higgins) in the presence of his wife was included in their slaughters. Never before in the history of Ireland was a movement towards peace by the power that occupied the country for 750 years received with warlike protest. The Catholic Emancipation Act was faulty. The Franchise Acts were faulty. The Land Acts were faulty. The Judiciary was imperfect for centuries. Yet the first measure that England resolved upon to give powers larger than those enjoyed by the States of the American Union for three-quarters of the island was greeted with Civil War. True, the country was partitioned, but that had been legalized a year before the Treaty was signed.

I wrote my brother:

Chapelizod,

22nd September, 1922.

“It is two weeks since you left Cork, and I have not heard from you. I received a bundle of letters to-day for the first time, but nothing from you. As this letter may not reach you, or may be read by others, I shall not say much.

On Saturday night I slept at Chester, and was next day motored to Devonport’s in Wales, and arrived home on Tuesday night.

A beautiful telegram from Rome reached me from Max. He and his family saw the Pope, who sent my wife, through him, a crucifix, and the kindest messages for both of us.”

Then came a fortnight’s anxiety about my brother, as to whom no tidings reached me. At length I heard from him, and replied:

Chapelizod,

7th October, 1922.

Your letter of the 10th September came on 3rd October. What a feat!

A week ago, a message came from Donegal from Mrs. Blackham, wife of the former editor of the Sunday Independent, asking me to secure her husband’s release. I had heard some hazy account of his arrest, and as I had him to lunch here last year, was anxious to befriend him. To my amazement when I tried to get him freed, I was shown a mass of propaganda which he composed, including stories about my conversation, to be published in the Irish World.

He attributed to me conferences with Griffith, whom I haven’t seen this year. I replied mildly, as his wife must be in ignorance of his performances. He is an English convert.”

The Coalition Government resigned in October, 1922, and Bonar Law became Prime Minister. A dissolution followed. I wrote Maurice:

Mail Boat,

20th October, 1922.

“The Morning Post to-day attacked Cope, while Sceilig in the Catholic Bulletin, in an article on Collins, treats him as the “serpent” in the late terrestrial paradise.

President Cosgrave made to-day the suggestion which I told you of as to myself. He said the proposal would astonish the Republicans. I don’t know if Bonar Law would object. My journey to London has nothing to do with this, and relates to the Bank of Ireland stock-register of British Funds which the Treasury wish to abolish.”

A proposal had been made that I should become Governor-General of the Irish Free State. I wrote my brother:

1 Temple Gardens, E.C.

23rd October, 1922.

“I spent the week-end at Cherkley, and told Max what was proposed as to myself, and he was satisfied it would be ratified. Yesterday Bonar Law called, and Max told him.

Bonar, I think, was favourable. I had a talk with him on the Bank register. He called me, as usual, “Tim,” I don’t write explicitly, lest my letter should be opened or go astray.

I saw Cope to-day, and he informed me he was told officially to put up my name.

The late Coalition leaders blame the Irish settlement for their breakdown, whereas what killed them was Chanak, Smyrna, and the Greek rout by the Turks.

If Lloyd George had dissolved instead of resigning, nearly all his Under-Secretaries and two Cabinet Ministers, Baldwin and Boscawen, would have resigned.

After the Carlton Club defeat Chamberlain would also have retired, and Lloyd George could only have gone to the country with a beaten host.

I think Ireland will not suffer from the change of Government. Of course the Boundary question is ticklish, I should not be surprised if the new Government compensated all the loyalists who have suffered. They were doing this as regards losses which were “pre-Treaty,” and if they include “post-Treaty” losses it would be a considerable benefit.” When I returned to Dublin, I wrote Maurice

Chapelizod,

26th October, 1922.

“The news I brought from London pleased the Provisional Government who said that if the proposal is carried, it will strengthen them and discourage their opponents.

The new Secretary to the Colonies told the head of his Department that it was a proper thing to do, and that he would recommend it to the Cabinet.

We may lose Cope, as Lloyd George is tempting him to quit the Civil Service and act as secretary to himself. The Daily Mail, after helping to drive out the Coalition, is now critical of the new Ministry.

The sale of The Times to Major Astor and Walter will divorce it from the Daily Mail, which is to the good. There are no Irish negotiations such as the papers rumour, though Dr. Hagan of Rome tried his hand while here. A big contingent of Free State troops left for Kerry yesterday, which doesn’t look like peace.

The de Valera papers just published were captured from his secretary in her office.”

Ulster Nationalists, unaware of the project to make me head of the Irish Free State, urged that I should stand for a Tyrone seat in the British Parliament. Had this come from a Convention instead of through private friends, my inclination would have been to accept it. I wrote my brother:

Chapelizod,

29th November, 1922.

“I am surprised you did not receive the letter in which I enclosed the Cardinal’s and Father Phil’s letters urging me to stand for Tyrone. They will edify the Irregulars, who, I suppose, seized them!

If you get The Times you will see what was rumoured about myself. I have not heard anything beyond what you know. The Daily Sketch yesterday had pictures and paragraphs treating it as a certainty.

The smashing of the Queenstown electric works shows great bitterness, as the local people alone are injured. The tone here is hopeful. A priest from Roscommon yesterday told me his county was absolutely peaceful.

As regards the Bank of Ireland “stock register,” Bonar Law had not even heard of the intended change, and was quite against it. The thing is the work of a civil servant who has been transferred to India. That such a proposal could be initiated without consulting the Prime Minister shows with what little wisdom the world is governed. Bonar had no knowledge of the intention to make a change! The Bank of Ireland is not free from blame for letting the matter pass without agitation, as every prospectus of Government stock they issued bore on its face a guarantee that the stock would be registered in that Bank in Dublin.

The ability to acquire riches, and the ability to protect them when acquired, seem to be two distinct faculties. One depends on individual effort – the other demands organization.”

The rumour spread that I was to become Governor-General of the Irish Free State, and I advised Maurice:

Chapelizod,

30th November, 1922.

“I am again bound for London to-morrow. I have been asked to call at the Colonial Office at 10.30 on Saturday morning. A Free State officer stayed here last night by order of the Authorities, without any request from me. He says the Irregulars in this district are no good, and that all the fighters are dispersed. He showed nothing but contempt for them, and says they are throwing away their weapons, and that Childers’s fate frightened them. While he doesn’t think they would hurt me, it is possible they might kidnap me.

From the document read yesterday by General Mulcahy it is plain that destruction of property is the Irregulars’ chief reliance.”

Griffith, his heart strings outworn, died in 1922. Coffins was slain in an ambush prepared by his former comrades, who thought that by killing him they could exact terms from Britain larger than he had won.

The father of Kevin O’Higgins was murdered on the 11th February, 1923. Kevin himself was spared until July 1927, when he also was assassinated.

The looting, burning and murdering continued until 1st July, 1923, when de Valera told an American reporter “the war is over.” A month later he denounced “the mad attempt to form a Government,” and prophesied that its members “will never cease to live in fear and trembling” (3rd August, 1923). He renewed the latter threat in the Dail in 1928 after he had taken the Oath of Allegiance.

On the 6th December, 1922, I was sworn in as Governor-General of the Irish Free State at my home in Glenaulin, Chapelizod, by Lord Chief Justice Molony. Though I clung to the house I had fashioned, I was requested by the Executive to take up residence in the Viceregal Lodge.

I shall end with some account of that Mansion and of the The Lodge fronts the Dublin and Wicklow mountains, which, until the reign of Henry VIII, bounded the English “Pale.” The story of the Park (told in Carte’s Ormonde, Howard’s Revenue Exchequer, and the Ormonde Papers) holds much of interest.

About 1170, Strongbow (Earl FitzGilbert, or Pembroke) invaded Ireland and claimed the island for Henry II. That King granted the Knights Hospitallers of St. John of Jerusalem the estate of Kilmainham, near Dublin, with a fishery in the Liffey. This foundation throve for four centuries. Henry VIII, in 1542, despoiled it and confiscated the Knights’ property.

When the counter-reformation under Queen Mary came, she made restitution to the Knights, but her step-sister, Elizabeth, expelled them for ever. Their lands lay profitless until the restoration of Charles II in 1660. In 1662, the Duke of Ormonde, as Viceroy, bought large scopes of ground to add to the Knights’ late premises in order to form a park. A wall was made for a couple of miles from Dublin to Chapelizod to enclose them, under a bargain between Ormonde and Sir John Temple (Speaker of the Irish House of Commons). To reward Temple he was given the acreage outside the wall. The Ormonde Papers show that Temple also received £200 in cash – the equivalent now to £2,000 – and set forth the names and wages of the masons.

After the Park was stocked with deer, Charles II, in the gallantry of those days, made it over to one of his ladies, Barbara, Duchess of Cleveland. Ormonde demurred, and to his firmness, which cost him sorely, Dublin owes the preservation to its citizens of that expanse of beauty. Barbara Villiers and the favourite, Buckingham, then sought Ormonde’s downfall.

On the night of 6th December, 1670, according to Carte (vol. ii, page 421), or seven years earlier, according to Pepys’s Diary (1st June, 1663), the Duke was attacked in St. James’s Street, London, when returning to his mansion in Piccadilly from a Corporation banquet to the Prince of Orange. (This house afterwards became the seat of the Dukes of Devonshire until 1924.)

After a struggle, Ormonde was rescued, but lay long abed of his hurts. His assailant was Colonel Blood, a disappointed Cromwellian, who intended to force him to Tyburn and hang him on the gibbet there, A year later Blood attempted to seize the Crown jewels in the Tower. Ormonde, after his recovery, was coldly received at Court. When he tried to kiss the King’s hand he was only given the tips of his fingers. Blood, however, despite the affair at the Tower, was examined by the King himself, through the influence of Barbara Villiers, instead of being tried by the ordinary courts. Although he confessed that, when he attacked Ormonde, he had a rope ready in his pocket to hang him, an estate in Ireland was conferred on Blood worth £500 a year. Yet Charles II, who set such a sad imprint on Irish affairs, left the American Colonies a noble memory by fostering toleration and representative government.

Ormonde’s Ranger of the Phoenix Park, Nathaniel Clements (ancestor of Lord Leitrim), built a mansion on the site of the present Lodge. Its colonnade was adopted as a model for the “White House” at Washington. Ormonde erected for himself a huge brick structure at Chapelizod (the village whence Tristan’s Iseult came), which was demolished about 1900.

The Lodge was offered in 1782 to Henry Grattan by the Irish Parliament as guerdon for his vindication of Ireland’s legislative but the place being in ill condition, he declined independence, the offer.

In 1904, a Blue Book of the Irish Board of Works reports that the lands outside the Park (across the Liffey) were, at my suggestion, repurchased by the Crown for public use. Lesser areas had been alienated permanently to afford sites for the Royal Hospital and for railway purposes.

George Wyndham, who loved the Park, helped in this re-acquisition. But for the War, much more would have been made of it, to pleasure the people.

Had I preserved my brother’s letters as he did mine, these pages would not have lacked lustre. when he was expelled from Cork, his health gave way. On his return, his house was burnt “officially,” and then came his death, which left me forlorn of more than a critic. – The End

DEATH OF TIM HEALY

At Chapelizod, outside Dublin, complications of jaundice, dropsy and heart disease brought Death last week to a bearded, brilliant gentleman with a testy tongue, Timothy Michael Healy, first Governor General of the Irish Free State, in his 76th year. Three years ago failing health made him resign the Governor-Generalship. Fortnight ago his condition became critical, relatives were summoned. Tim Healy (nobody ever called him anything else) died in the night.

Even 15 years ago if anyone had seriously suggested in the House of Commons that Tim Healy was destined to become His Majesty’s Representative in Ireland, laughter would have shaken the chandeliers. Timothy Michael Healy was born in Bantry, County Cork, in 1855, son of the local poorhouse guardian. His earliest memories were of creaking farm carts marked with rude white crosses, piled high with corpses of the famine on their way to common burial in the lime pits. These were not memories to make any boy a loyal British citizen. At the age of 14 he had taught himself shorthand. At 17 he made his way to England, worked as a railway clerk, a reporter. He first attracted attention by the brilliance of the political articles that he sent to his uncle’s Dublin paper, The Nation.

After his return to Ireland he became private secretary to his hero, the late great spade-bearded Charles Parnell. Home Rulers enthusiastically elected him to Parliament at the age of 25. At 28 he was arrested and imprisoned for making seditious speeches.

With Parnell he toured the U. S. several times, collecting money from fervent Fenians for The Cause, but he finally broke with Parnell after the latter’s life with Kitty O’Shea had become an international Victorian scandal.

In the House, on the lecture platform, Tim Healy was known as a master of invective. Time & again he was dismissed from Parliament for abusive language. Each time enthusiastic Irish majorities voted him in again.

“Mr. Speaker, if the noble Marquess thinks he is going to bully us with his high and mighty Cavendish ways, all I can tell him is he will find himself knocked into a cocked hat in a jiffy, and we will have to put him to the necessity of wiping the blood of all the Cavendishes from his noble nose a good many times before he disposes of us.”

“A fine national anthem we’ll have,” chortled Testy Tim when he heard that Ulster was to be left out of the Irish Free State. ” ‘God Bless the Greater Part of Ireland.’ “

For all his intense nationalism, Tim Healy generally kept out of jail, never joined the Sinn Fein, and thoroughly disapproved of the Easter Rebellion of 1916.

It has been said that picking Tim Healy for first Governor General of the Free State in 1922 was the most brilliant political stroke that Prime Minister Bonar Law ever made. King George would never have approved anyone connected with Sinn Fein. Catholic Ireland would not have accepted anyone who was not a confirmed Home-Ruler.

When the Countess of Oxford was a little girl she was solemnly introduced to the late great William Ewart Gladstone.

“He was quite nice,” said candid Margot afterwards, “but you see Mr. Healy has really spoiled me for all other men.”

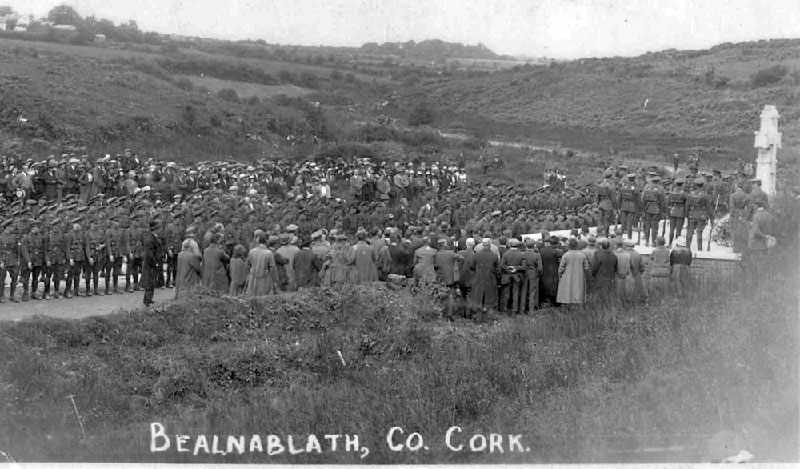

THE BEALNABLATH MONUMENT

Unveiling of the monument to General Michael Collins at BealnaBlath aug 2nd 1924 by W.T.Cosgrave Chairman of the Free State Government

The cross that was erected in Beal na mBlath, loitered for ninety weeks in the shed of the brother of Dublin sculptor, Michael Shorthal – ninety weeks that had changed it from an unwanted gift to a cheap solution. In February 1923, the Governor General Timothy Healy, acting on behalf of an anonymous ‘Irish Lady in New York’, suggested the erection of this cross over the grave of Michael Collins in Glasnevin Cemetery.

The Army council declined the offer in March, refusing to countenance the erection of a monument while the grave was still in use for military casualties, refusing because they had not yet paid for the grave. Healy had been careful in his negotiations with the cemeteries committee when they brought up the price of the grave. He told them nothing of the man this cross was to honour, nothing in case the committee would ‘use my desire to do homage to a great memory as a leverage to screw a perhaps higher demand’, from the government for the plot. The Lady above mentioned may have been Hazel Lavery.